How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

Editor note: Untapped Cities columnist Janos Marton, New York City lawyer, activist and founder of the website janos.nyc has been working on a full history of Williamsburg. While this project will be in progress for some time, a few months of research has already yielded fun facts about the popular Brooklyn neighborhood, which he will share with us today. In a fun anecdote, he says:

I got to drop one at a biker bar on Saturday night. A group of bikers were mocking the real estate industry’s generation of new neighborhoods, like “East Williamsburg”, and the latest, “Bushwood.” Somehow “Bushwick” got mockingly thrown into the mix, and I felt obliged to point out that Bushwick was actually named by Peter Stuyvesant in 1660, so unless one wants to argue (and one could) that “Bushwick” was a very old school real estate marketing gimmick, at least that neighborhood can stand on its name.

Without further ado, ten interesting facts about Williamsburg, before it was cool–before it was even Williamsburg.

The geographic area that includes Williamsburg was first purchased in 1638 by the Dutch West India Company from a group of Canarsee Indians sachems, the same tribe that likely sold Manhattan. The purchasing price was greater than Manhattan, a harbinger of today’s real estate market, and the deal similarly involved a collection of European tools and wampum.

There is little evidence that the Canarsees actually lived in future Williamsburg, much of which was set on a swamp called “Cripplebush.” (Cripplebush is an anglicization of the Dutch word for “scrub oak.”) The Canarsees likely used the area seasonally for hunting and fishing, but their various settlements were elsewhere. The “purchase” was likely understood by both sides to allow common use of the land until it was developed, which took some time.

South 4th and Bedford Avenue today

One of the first homes built in the neighborhood was on the future intersection of South 4

thand Bedford Avenue. Named “Keikout” (Dutch for “look-out”), it was first a refuge in case of Indian attacks, and then a boarding house, and its most famous tenant was Captain William Kidd. Kidd based many of his pirate voyages out of Manhattan, where local merchants invested in his operations, but he had a soft spot for Keikout because, according to legend, one of his former lovers was buried near there, passing away while he was out at sea. With his dashing style and questionable accumulation of wealth, Kidd may have been the first true Williamsburg hipster.

Captain Kidd, one of Williamsburg’s first regular visitors, entertaining guests.Painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris from Wikimedia Commons

After a couple fits and starts, thanks in part to an ill-advised war, the Dutch West India Company actually got to settling the land around Williamsburg. In 1660, a group of Frenchmen (under Dutch supervision) set up a small village that local governor Peter Stuyvesant named “Bosjwick”, or “place of the woods.” Bushwick, located at approximately the intersection of Metropolitan and Bushwick Avenues, became the northernmost Dutch village in the borough. A smaller settlement named Het Strandt (“The Strand”) was laid out along the East River, near today’s Southside.

Bushwick Inlet

The Bushwick Inlet, best known today for the controversy over the future Bushwick Inlet Park, used to be quite a bit longer and more significant to the neighborhood’s geography. Though it is now cut off by Kent Avenue, it used to wind its way diagonally east and south, creating a natural border with Greenpoint, flowing as far as the intersection of North Seventh Street and Seventh Street (Havemeyer).

Speaking of geography, one of the challenges to writing about Williamsburg’s history is the shifting names for the relevant areas. Before Williamsburgh was founded (the “h” was dropped in 1855 when Williamsburg merged with Brooklyn) the settlement was part of Bushwick, which covered most of northern Brooklyn. Of course, back then it wasn’t called “northern Brooklyn,” because until the 1850s Brooklyn was still a town/city to the south in Kings County, not a full borough. When the British took over from the Dutch in 1664, the modern borough of Brooklyn was named “Kings County.” That leaves Cripplebush, Bushwick or northern Kings County, all of which mean slightly different things geographically, for describing the land of future Williamsburg before it was incorporated.

Photograph by Michelle Young

Kings County wasn’t exactly a hotbed of revolutionary fervor. In 1776, the whole borough was either undeveloped forest or farmland, mostly under the control of the same Dutch families who moved there during the Dutch West India Company era. These Dutch descendants had little interest in the conflict between the British Empire and their quasi-British subjects. If anything, wealthy farmers saw no need to jeopardize their financial holdings by picking a fight with the empire.

There were exceptions, of course. Bushwick sent a delegation to various revolutionary conventions, led by John Titus, whose family farm would later serve as the foundation of the first Williamsburg development. Captain Titus formed a Bushwick Militia, which included young men from several prominent local families. In general, however, the area was home to minimal rebel activity during the subsequent British occupation of New York and Kings County, which lasted for the entire Revolutionary War.

The British handling of the Revolutionary War was unpopular in England, and an overstretched empire was forced to rely on mercenaries to outfit its colonial fighting force. King George III turned to blood relations in Germany, including a large contingent from Hesse-Cassel province, known as the Hessians. The Hessians were known for fighting with “skill and savagery,” which they displayed aplenty during the Battle of Brooklyn (in present-day Prospect Park) where they gored hapless Americans with bayonets, even after surrender. Their reputation followed them during the occupation; the British saw fit to house them in Bushwick, where they took over local homes and burned fences for firewood. In general, the British army needed all the wood it could get its hands on for military purposes, and it chopped down much of the Bushwick forest, which opened new areas for farming after the war.

The most tragic story of the Revolutionary War was the thousands of American soldiers who died in captivity, many aboard awful British prison ships. Some estimates put the death tolls at 11,000, more than the number who died in combat. Some of the most notorious prison ships, where men were packed like sardines and malnourished until they passed away from disease or starvation, were anchored in Wallabout Bay, where the Brooklyn Navy Yard is today. The daily accumulation of dead bodies would be dumped into the East River or hastily buried on its eastern shores. For years after theRevolution, people walking the sandy beaches of Williamsburg might stumble across skulls and other bones of the departed. Many skeletons were given proper burials following a donation by the young Society of Tammany, and a monument to the soldiers sits in Fort Greene Park.

Photograph by Sofia Andrade A. Cirino

At the close of the 18th century, pre-Williamsburg was comprised mostly of large farms. (Though there was still a substantial wooded area covering much of today’s “Northside.”) The farms were named for the families that developed them, and many names are familiar to people who have strolled around the area: Berry, Boerum, Meserole, Powers, Skillman, and Devoe. Other prominent farmers like Titus, Miller, Waterbury and General Jeremiah Johnson did not have streets named for them, and live on only through their stories. Like the rest of Kings County, Bushwick’s big farms were home to a large slave population. From the 17th century until the last days of New York slavery in the 1820s, slaves accounted for roughly 20%-30% of the local population, with only a small free black population remaining after 1827. (Coincidentally, both the year of Williamsburg’s incorporation and the year New York completely outlawed slavery.)

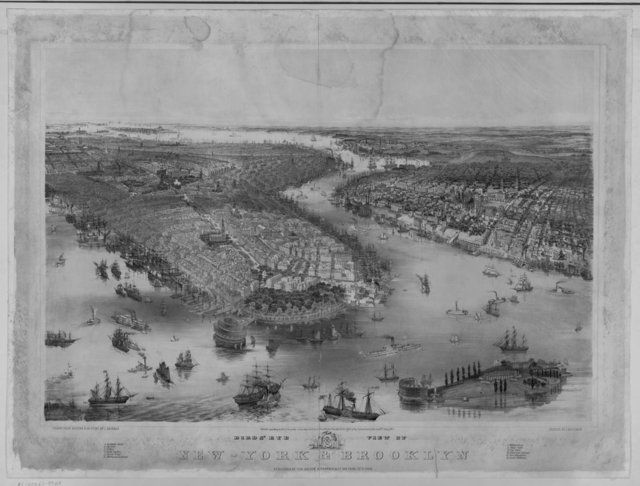

Bird’s Eye View of Manhattan and Brooklyn circa 1851. Image via Library of Congress

If you had to cross the choppy East River waters in a rowboat, who better to put your mind at ease than someone named Hazard? James Hazard lived in Corlears’ Hook in the Lower East Side, and in 1797 he became the first ferry operator to traverse the East River from the shores of Bushwick, on today’s Grand Street. At the time, it is unlikely he ferried regular commuters, but many farmers from the area used his service to bring their produce to the Lower East Side markets, which built up around Manhattan-side ferry landing spots. Hazard had the field to himself for a few years, and even got into the real estate game, but his enterprise eventually bankrupted.

Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center in Bed-Stuy, named after Richard M. Woodhull.

Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center in Bed-Stuy, named after Richard M. Woodhull.

One of Hazard’s rival ferry operators was a young scion named Richard M. Woodhull, cousin to Abraham Woodhull, a founding member of the Culper spy ring out of Setauket immortalized in the recent AMC show TURN and to Nathanial Woodhull, the Revolutionary War hero. Richard Woodhull, whose name lives on through a giant hospital, deserves credit as the first to recognize the potential for a bustling town in what is now the heart of Williamsburg. In 1802, Woodhull purchased 13 acres of land alongside the East River around what is Metropolitan Avenue, and began hyping the city’s newest suburb. To market his development, he asked a friend to survey the land: the well-respected military planner and nephew to Benjamin Franklin, Jonathan Williams. Hence the name.

The land speculation that Woodhull set off did not make him rich, or endear him at first to the locals. According to 19th century historian Henry Stiles, however, the farming class of future Williamsburg came around to Woodhull’s point of view: “Instead of slowly amassing money by plodding labor and close-fisted huckstering, they found fortunes fairly thrust upon them by the enhanced value of their farms; due to the enterprise of others, whom they considered as Yankee intruders. They hesitated at first, dazzled by the prospect, and suspicious of the motives of those who offered. But finesse prevailed and the first purchase made – the rest was simply a matter of time.”

Next, check out the real life locations featured on the AMC show TURN about America’s first spy ring.

Subscribe to our newsletter