Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

Slave market marker at Wall Street and Water Street

When you think about slavery, New York City rarely comes to mind, but there’s actually a deep history entrenched in the streets and buildings of New York. As we showed before, the Underground Railroad had a large presence here and finally this year, in an effort to recognize #blacklivesmatter, New York City has finally acknowledged that it was once home to one of the biggest slave markets in the country. In June, Mayor de Blasio unveiled a new plaque marking the spot on Wall Street where the slave market once stood, dedicating it to the thousands of enslaved people who passed through.

Inspired by this historic event, here are 10 things you may not have known about New York City’s slave market.

Slavery in America is most commonly associated with southern plantation but many city dwellers also owned slaves and New Yorkers were no exception. In fact, New York was the biggest slave owning colony in the North. By 1741, 1,800 people amid a population 10,000, were black slaves. Blacks consisted of one third of the city’s workforce and one in every five households owned at least one slave. One Scottish traveler even complained, “it rather hurts a European eye to see so many negro slaves upon [New York’s] streets.”

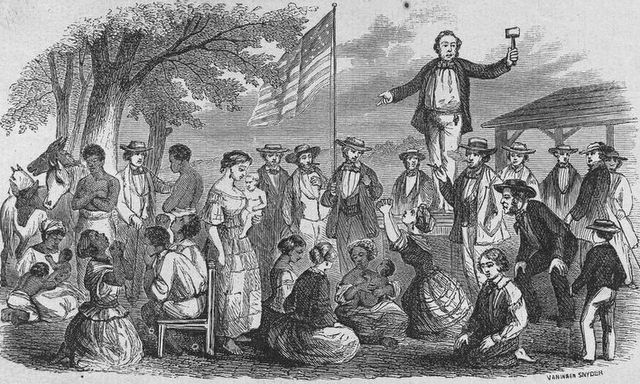

Many colonists feared that slaves would organize an uprising, given the density of the slave population. Unlike plantation slaves, city slaves had considerable mobility and were often left unsupervised. Slaveholders decided the best way to thwart rioting was to limit the amount of time slaves could spend with each other. They created a slave market to continuously buy and sell off slaves, preventing slaves from getting “too comfy” so-to-speak. A law was passed in 1702 that prohibited slaves from gathering in groups of three or more.

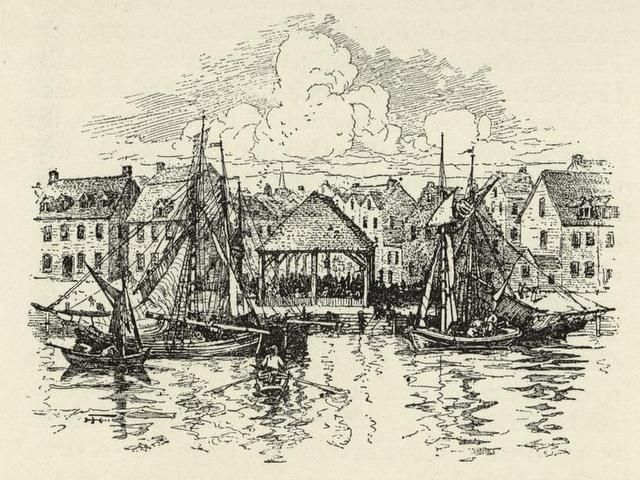

Corner of Water Street and Wall Street

On December 13, 1711 the first slave market was established where Wall Street reaches the East River. The location was actually a hang out point for slaves who had down time from work, making it a decisive spot to break up organization. The Common Council, now known as City Council, passed the “Law Appointing a Place for More Convenient Hiring of Slaves,” stating “that all Negro and Indian slaves that are let out to hire… be hired at the Market house at the Wall Street Slip…”

In 1726, another ordinance was passed that declared this location was the sole public market for selling corn, grain, or meal, giving rise to its name, the Meal Market.

Meal Market became one of the most profitable slave markets in the country – second only to Charleston, South Carolina. New African slaves arriving at Pier 17, now the popular tourist destination South Street Seaport, were taken to Meal Market where they were auctioned off. The business of slave trading became an integral part of New York’s economy. Its profits tricked into the city’s networks of lawyers, clerks, dockworkers, carpenters, and more.

1916 Redrawing of The Castello Plan, map of 1660 New Amsterdam via Wikimedia Commons. The wide street is now Broadway, and Wall Street is the line with guard towers on the left.

Wall Street was once a wall… built by slaves. Slaves (and free Africans) contributed a great deal to the early construction of the city, including the wall from which Wall Street derives its name. In 1653, under the Dutch Governor William Kieft, the wall was constructed to protect Dutch settlers from Native American raids.

Running from river to river, it consisted of a walkway and wooden fence made up pointed logs 18 inches wide and 12 feet long. The African slaves who were responsible for its construction were owned by the Dutch West India Company. Some of them were actually “half-free,” meaning they could own property, testify in court, bear arms, attend church, and marry. However, their children would not be considered free.

New York is home to two of the most gruesome slave rebellions in American history. The first occurred on April 6, 1712, when twenty-four African slaves gathered by the East River and started setting fires. They drove their slaveowners out of their homes and into a trap where they ambushed them. Although their initial plan did work, the magic powder they used to make themselves invisible did not. The next day they were captured in the nearby woods. Six of the Africans killed themselves immediately. Seventy black men were arrested, thirty-seven were indicted, twenty-three were convicted, and of the convicted, nineteen were executed. None received legal counsel.

Similarly, in April 1741, ten fires were set across Manhattan. The city erupted into hysteria and cried slave conspiracy. This time, the city rounded up two hundred slaves and accused them of conspiring. Under duress, eighty slaves confessed. Thirteen were burned at the stake, setting a horrific example of punishment. Seventeen were hanged and seventy more were shipped to the Caribbean where slaves conditions were so severe, the punishment was considered a death sentence.

New York Stock Exchange

The signing of The Buttonwood Agreement, which created the New York Stock Exchange, was signed just a few blocks away from the location of the Meal Market. Twenty-four brokers and merchants designed the Buttonwood Agreement to regulate trading securities and standardize commission compensation. The Agreement was signed on May 17, 1792, at 68 Wall Street under a sycamore tree.

While the Meal Market had already been destroyed by the time of its creation, the Buttonwood Agreement dealt with many financial issues surrounding the slave trade.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Meal Market had undergone some renovations and it became a popular spot for the Merchants Coffee House to meet as well. These merchants, who belonged to a much more aristocratic class, feared the slave market would be an obstruction to the prospects of this new, more respectable industry. In 1762, the Common Council drafted a petition stating that “[the Meal Market] occasions a dirty street, offensive to the inhabitants on each side and disagreeable to those that pass and repass to and from the Coffee House, a place of great resort, that same be removed.” By that February, they successfully tore down the Meal Market after five decades.

Although the market closed, men, women, and children continued to be bought and sold throughout the city.

Between the years 1857 and 1862, while the Civil War was being fought, America experienced a tremendous resurgence in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, which had been illegal for five decades. And at the forefront of this highly illegal activity was New York City. The city’s legitimate trading tries with Africa made it easy to mask illicit slaving activity. In 1857, the New York Journal of Commerce reported that,”downtown merchants of wealth and respectability are extensively engaged in buying and selling African Negroes, and have been, with comparatively little interruption, for an indefinite number of years.”

In 2012, during the height of the Occupy Wall Street movement, protestors signed the first online petition to recognize the city’s deep involvement in slavery. The petition reads:

December 13th is the 300th anniversary of the law establishing the first slave market in New York. That market was located at the end of Wall Street where present day Water Street is. Yet there is not a single sign, plaque, marker, statue, memorial, or monument with any reference to slavery or the slave trade in Lower Manhattan…

…[Slaves’] contribution to New York is and has been completely invisible. After 300 years it is finally time to tell their story.

Next, read about 10 stops of the Underground Railroad in NYC and about Lower Manhattan’s secret history of slips. For more information about New York history of slavery, check out Slavery in New York and Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery.

Subscribe to our newsletter