NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

The Manhattan Bridge may not be New York’s most beloved or attractive bridge but it still has a deep history full of unknown secrets. After a decade of planning, three different architects, and many political changes this bridge tells a fascinating story about turn-of-the-20th-century Manhattan architecture and its life moving forward. Completed in 1909 under the supervision of chief engineer Leon Moisseiff, the country’s first modern suspension bridge spans from Canal Street in Chinatown to Flatbush in Brooklyn.

Take a look at some of the secrets we discover, with special thanks to Dave Frieder for contributions and photos.

After finally closing the gap between Brooklyn and Manhattan on May 24, 1883, development in Brooklyn skyrocketed. Both boroughs were eager to keep making “flood gates” from the overpopulated areas of Manhattan to the underdeveloped areas of Brooklyn. Relieving traffic between the boroughs was an immense task to undertake. In 1898, both the elevated train and fords electric trolley line were squeezed on the Brooklyn Bridge, leaving only enough room for a single lane for horse and carriage traffic. Rumors of a possible collapse caused a fatal stampede in 1883. And according to the Bowery Boys podcast, by June 29, 1898 the weight from the hundreds of vehicles buckled the bridge, making it apparent that something immediate needed to be done to address the traffic issue. Thus, the idea for the Manhattan Bridge was born.

View of Brooklyn Bridge from the top of Manhattan Bridge. Photo by Dave Frieder.

The second design for the Manhattan Bridge by Gustav Lindenthal borrowed from both the Brooklyn Bridge and the Williamsburg Bridge. Drawing from the Brooklyn Bridge, it was proposed to have both vertical and suspender ropes and diagonal cable stays. And drawing from the Williamsburg bridge, it was supposed to have massive steel towers and deep stiffening trusses (in fact, the trusses were supposed to be 15 feet deeper than the Williamsburg Bridge). It was also going to have towers that were crowned with ornaments, similar to those on the Williamsburg Bridge. Unfortunately, this interesting concept was rejected by the New York City Art Commission, which was very influential at the time.

In 1901, architect and commissioner of the New York City Department of Bridges, Gustavo Lindenthal, presented plans for the “Suspension Bridge Number 3” (which was later remained the Manhattan Bridge). His first design, the Brooklyn/Williamsburg Bridge hybrid, received support from Mayor Seth Low but was rejected by the New York City Art Commission. Two years later, he proposed a second “eyebar/suspenders” plan that was more radical than any other American bridge of its time.

In the heat of debate over the beauty and practicality of his new design, Mayor George McClellan was elected. He was invested in the Brooklyn Bridge architects, Roebling Wire Works, which had political and financial links to Tammany Hall. Roebling supported traditional wire-cable designs and thus Lindenthal was ousted as bridge commissioner. McClellan appointed George E. Best as the new commissioner and Best, with little experience in this line of work, opted for a cheaper, more conventional bridge design.

Part of Lindenthal’s radical eyebar design was to use two-dimensional tower profiles rather than the three-dimensional profiles seen on the Brooklyn and Williamsburg Bridges. In the two-dimensional design, there are four columns in each tower, creating a less rigid design and allowing greater flexibility, expansion and contraction. Although the new engineer, Leon Moisseiff, implemented Lindenthal’s idea, the 322-foot tall towers support wire-spun cables that more typical of traditional suspension design.

Satellite-looking dishes on sphere. Photo via Dave Frieder.

While most are now covered in graffiti or have been redone, the Manhattan Bridge has an outstanding number of architectural embellishments that you can still find if you look closely. Retro satellite-looking dishes that were way ahead of their time can be found on some of the towers. In addition, on the canopies, which are used to cover bronze plaques, there were originally white frosted lights that helped light the Manhattan skyline. Most still exist but have been replaced with a (in Dave Frieder’s opinion slightly less attractive) clear glass.

Manhattan Bridge is known for its baroque “Court of Honor” arch and colonnade entrance on the Manhattan side, designed by New York’s Carrère and Hastings firm. The Brooklyn entrance also once had a more elegant entrance that no longer exists. When the bridge first opened, architect Daniel Chester French had sculpted two females that were supposed to embody both Brooklyn and Manhattan, standing on either side of the bridge. The statues were taken down in the 1960s to improve visitor movement, but you can now find them in front of the Brooklyn Art Museum.

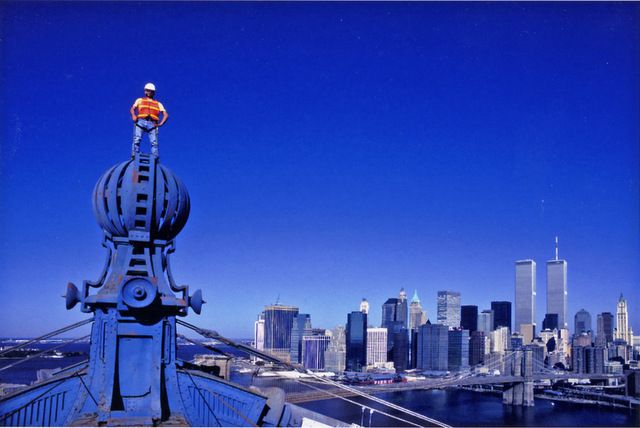

Photo via Dave Frieder.

Engineers Othniel Foster Nichols and Leon Moisseiff developed the “deflection theory” that would be implemented on the Manhattan Bridge. This theory stated that the following three opposing forces act on the deck and suspension cables:

The deflection theory accounted for the economies of material, cost, and time. But in 1909, it did not account for the development of subway traffic on the outer parts of the lower deck.

Since the 1980s, New York City Transit has put in roughly $920 million dollars in efforts to fix the bridge’s core infrastructure and after two decades of repairs, it reopened in the early 2000s. The bridge now goes under routine inspections and is structurally sound, but at times you can still feel a sway when a B or Q goes whirling by.

Photo via Dave Frieder.

Some may question the decision to paint the Manhattan Bridge the deepish blue that it is – but it is actually the official color of the borough. The bridge was originally painted gray but in the 1970s it was repainted to as an homage to the Dutch tiles – best seen in the 17th and 18th century white-and-blue Dutch pottery you can find at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Moreover, according to bridge expert Dave Frieder, “Manhattan Bridge Blue” is the official color of the borough. He says the original paint can still be found in the columns and around the main colors.

Photo via Dave Frieder.

Next time you’re walking down the Manhattan Bridge, look past the gates unto the original railings and you might be able to spot a unique diamond pattern. You can also spot this pattern below the walkway and on top of the towers.

Next read about the Top 10 Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge and the 10 Fun Facts About the Williamsburg Bridge.

Subscribe to our newsletter