MetroCards to Masterpieces: Meet Artist Thomas McKean

Get a behind-the-scenes look at the work of a local NYC artist who turns MetroCards into works of art!

The new book, The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building is a historical and architectural history, deliberately eschewing the gossip that could easily fill the pages of a book with such a name. Nearly at the end of the book, the author, historian Andrew Alpern, accounts for this, stating “As almost ever article about the Dakota will tell you, much of its renown derives from its stellar list of dramatis personae. While on that score this book may disappoint by not providing the juicy details and tabloid gossip, several now-departed former residents maintained distinctive apartments in the building…” As such, this book is well-targeted for our reader and these secrets, which we sourced from the book, fall within the realm of architecture rather than popular culture.

Indeed, even without the “juicy details,” the Dakota has a fascinating history. Built with a budget of $1 million (equivalent to $24 million today), it ended up costing somewhere between $1.5 and $2 million in the end. Construction took four years, from 1880 to 1884, and by that time, the man who single-handedly brought it to life had died. Designed as a luxury family hotel, the 54 suites ranged from 5 to 20 rooms, with 500 rooms total. Its construction dispelled the myth that construction on the Upper West Side was inhospitable and heralded a new wave of housing, which included the whole range of New York City housing–from tenement, to brownstone, to apartments. As reported in The New York Sun in 1999, “a splendid new city built up where five years ago there were only rocks, swamps, goats and shanties.” The Dakota also made apartment living not only acceptable, but desirable.

Here are ten of our favorite secrets we learned from the book The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building.

Edward Clark, the visionary behind the development of The Dakota was originally a lawyer. He found a partner in Isaac Merritt Singer, a tinkerer who would have thrived in today’s makerspaces. In exchange for ownership interest in various inventions, Clark provided the necessary legal expertise to get Singer’s inventions past legal claims and through the patent process and came to own half of the Singer company. Clark’s shrewd business sense and his talent for marketing ensured the success of the Singer company and would come into good use in the development of The Dakota.

Image from Library of Congress

Image from Library of Congress

When Clark was dreaming up the idea for The Dakota, apartment living in New York City was an entirely new concept. First, it was associated with tenement living and considered undesirable. Its other relative, the hotel “were rather disreputable places, often connected to a tavern or inn…They served a useful purpose in 18th and early 19th century, but ‘nice’ people wouldn’t choose to live in such places, “writes Alpern in The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building.

As such, apartment construction for the middle and upper classes was a whole new concept and Alpern traces the earlier attempts in detail to show why The Dakota was so revolutionary, and continues to be an icon for luxury apartment buildings. He writes, “in retrospect it is perhaps too easy for us in the 21st century, from whom luxury apartment living is seemingly embedded in our DNA, to forget that the 1870s was still a new frontier, undefined and not even secure in the abstract.”

Like his work for the Singer company, Clark had to create demand for a new type of living. As Alpern writes, “For the Dakota, it was upper-class housing accommodations at a palatial level of luxury, set in a newly-developing Upper West Side whose potential for long term growth was not completely obvious to those with conventional wisdom.” Indeed, when you look at photographs of the Dakota under construction, you see it side-by-side with clapboard houses and farmland – a sharp contrast with the level of development on Manhattan’s east side, propelled by ferry connections to Brooklyn and other desirable features.

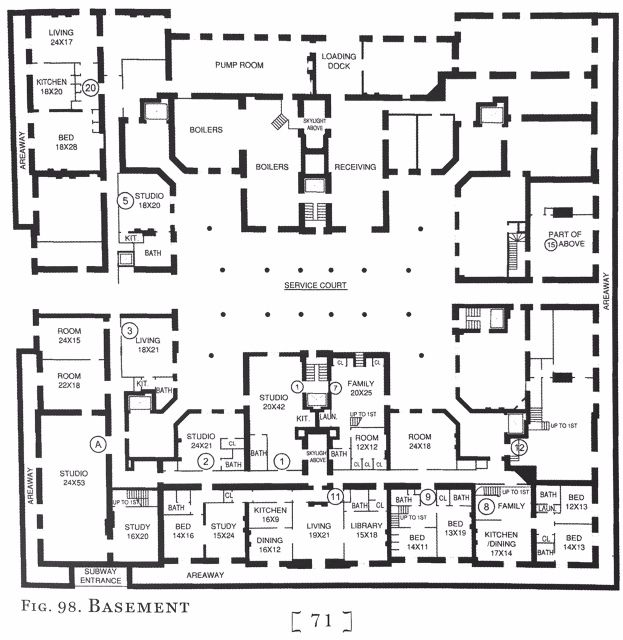

Floor plan by Mia Ho from The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building

Underneath the celebrated courtyard of The Dakota is a lower level courtyard with exactly the same dimensions as the public one. Accessed via a driveway from the rear side along 73rd Street, this lower level courtyard was constructed to manage services, deliveries, and access for staff, as the service elevators and staircases commence from this level of the building. It is lit by skylights cleverly “contained within a pair of decorative fountains at the street around which the carraiges could turn.” In 1891, The Dakota architect H.J. Hardenbergh was compelled to respond to an article in American Architect and Building News that stated that the service entrances were on the same level as the main courtyard, an error he believed the result of the basement plans having never been published. In his reply, he concludes contending that the hidden courtyard below has provided “perfect quiet and seclusion for the main court-yard.”

Alpern addresses an important origin myth about The Dakota, something he finds has been repeated “in scores of guidebooks and supposedly authoritative histories,” similar to the myth of that the Redstone Rocket poked a hole in the ceiling of Grand Central Terminal. Alpern points out that The Dakota myth always appears without a source and that contemporary articles from the time The Dakota was being built do not refer to the “supposed remoteness of the area.” The first report of the origin story as we know it today did not appear until 1933, in the New York Herald Tribune when building manager George P. Douglass mentioned it: “Probably it was called ‘Dakota because it was so far west and so far north.” Alpern believes that since Douglass knew members of the Clark family and the staff of Edward Clark, “for someone of with his tenure at the building to present the story as a casual conjecture hardly provides the ring of authenticity.”

In the era that The Dakota was being developed, safety was a great concern for potential buyers and renters of apartments, having heard about the fire safety problems in tenement apartments. One way Clark and Hardenbergh assuaged that fear was by placing hazardous equipment in a separate building or location nearby. The Van Corlear apartments on 7th Avenue between 55th and 56th Streets were a testing ground for Clark and Hardenbergh, who moved the utilities into a small building next to the apartment. The Dakota was a much larger undertaking so the heating system would need much more space than what was allocated for the Van Corlear. In addition, Clark wanted a plant to generate electricity and lighting for The Dakota and the rowhouses he had in the works nearby.

The solution was to use a plot of land next door along 72nd Street and place the boiler and three electric dynamos underground, above became a small, landscaped park. Hedges were planted to conceal the roof of this structure, and later tennis courts appeared. Clark also supplied water for The Dakota by digging an artesian well on The Dakota property, going down 365 feet to find it. In the mid-20th century, Edison Electric Company brought its services to the neighborhood and the utilities built by Clark and Hardenbergh were no longer needed. They were removed and replaced by car parking, which in turn was sold.

In a 1933 Herald-Tribune article, the writer mentions that this car parking/lawn next door, was “worth $350,000 [sic], and more in boom times, extended for half a city block towards the west, adequately preventing upstart structures from jostling the Dakota or even approaching close enough to place it in shadow.” Originally, there was a stipulation that any new building atop this plot of land could not be taller than The Dakota, but that was removed in order to enable a sale. This would become the Mayfair Apartments on 72nd Street.

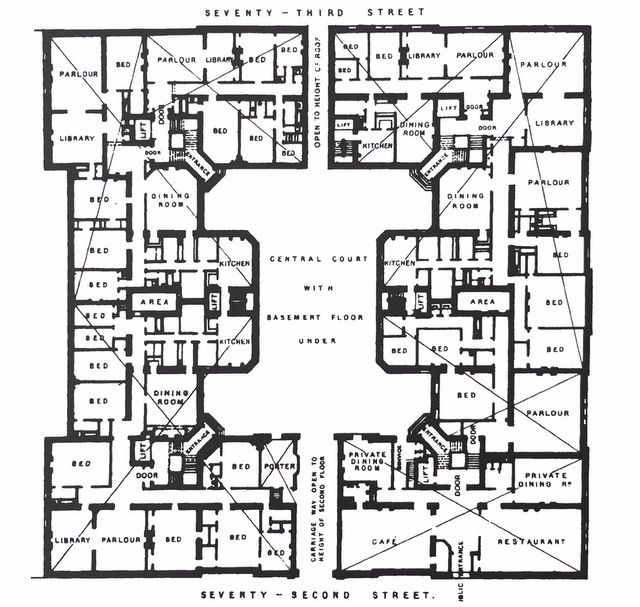

Alpern tells us that the original drawings and documents are lost, but published descriptions give clues as to what was intended. A floorplan with the Royal Institute of British Architects show a cafe and restaurant on the first floor, with a public entrance along 72nd Street (close to Central Park West). This never came to fruition and the dining room of The Dakota was limited to residents.

To support the dining facilities, which included a main dining room, a private dining room, and a reception area, the basement of The Dakota had a kitchen and service spaces. Residents could also order what is essentially room service from these facilities, which existed until after World II. After this, it was converted into an apartment/gallery for the artist Giora Novak.

East Roof Detail, 1965. Image via The Library of Congress

There is quite a lot of eclectic ornamentation on The Dakota, including double dragon iron supports on the railings and grotesque like details. On a gable on the south facade is the date 1881 (which Alpern suggests is the date the construction of the building itself began, while foundation work began in 1880) and the head of a “perhaps-Dakota Indian.” There are two circular portraits over the entrance at 72nd Street and another two above an arch on the Central Park West side. Like the subjects carved in the lobby of the Woolworth Building, there is no record of who these people may be and none look like Clark or Hardenbergh. Alpern suggests that one above the main entrance is “strikingly close” to Isaac Merritt Singer and the one next to it his last wife. The subject of the portraits along Central Park West remain a mystery.

On floor plans for The Dakota, you can see a back entrance to the courtyard along 73rd Street. Alpern writes that “before long, [this entrance] was closed off and used only for the entrance and departure of funeral participnts.”

Peter Illiyich Tchaikovksy was the opening night draw for the new Carnegie Hall in 1891, where he conducted five pieces. In a letter to a friend, he noted that he returned after a rehearsal to the “immense house where [music publisher Gustav] Schirmer lives…We found a number of people there who had come merely to see me. Schirmer took us on the roof of his house. This huge, nine-storied house has a roof so arranged that one can take quite a delightful walk on it and enjoy a splendid view from all sides. The sunset was indescribably beautiful. When we went downstairs we found only a few intimate friends left, with whom I enjoyed myself most unexpectedly.”

He also kept a notebook entitled Trip to America, inside which he noted humorous musings wondering whether the water was safe, what type of hats men wore and noted “in other countries, if somebody comes up to you and they’re nice, you suspect, ‘What do they want?’ Here in America, they don’t want anything. They just want to be nice.”

Originally, The Dakota entrance featured two, free standing cast-iron lanterns atop a pedestal. These impressive structures began with multi-armed lanterns, then had central globes. At some point, the lanterns were moved next to the curb of the road instead of just in front of the facade, and then removed completely (likely when 72nd Street was widened). The gas lanterns you see today attached to the wall of The Dakota were installed at this time and the metal sentry booth was added.

Get the book The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building.Next, read about 12 crazy facts about the nearby Ansonia Hotel and see more vintage photographs of The Dakota.

Subscribe to our newsletter