Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

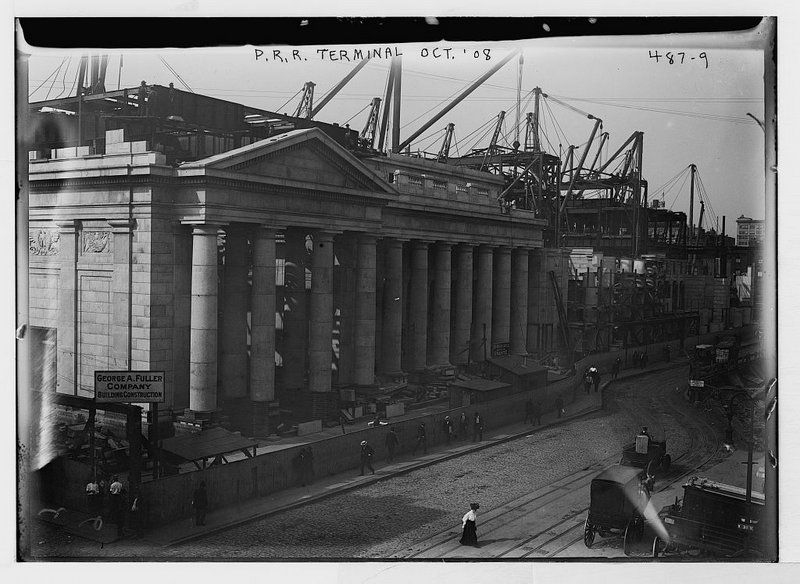

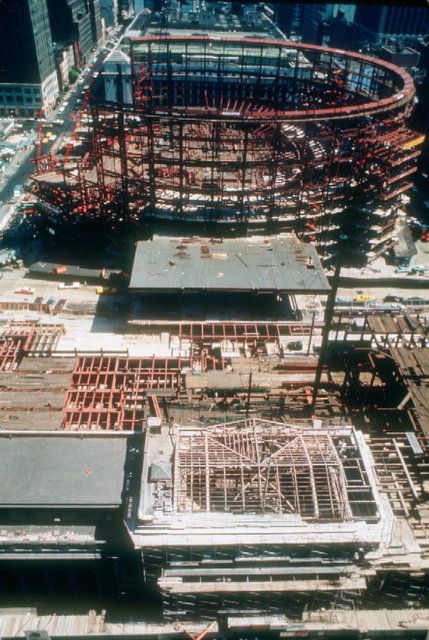

The destruction of the original Penn Station, which began on October 28, 1963, is largely considered one of New York City’s greatest sins. Designed by the illustrious architecture firm of McKim, Mead, and White, the sprawling structure was a Beaux-Arts masterpiece. Opened in 1910, the building would survive for just over fifty years before being demolished to make way for Madison Square Garden.

Over the years, we’ve tracked down remnants of the original station, from the 22 stone eagles that flanked its roofline to architectural remnants inside the current transit hub. As Penn Station undergoes another transition, we’re looking back at the very first iteration. For this list of secrets, we consulted Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers, our resident Penn Station expert and playwright of the previous off-Broadway play The Eternal Space. Here, we dive into his favorite secrets and share some rarely-seen photographs from the show.

The Pennsylvania Railroad had to demolish 500 buildings and displace roughly 6,000 people in order to build Penn Station. The workers were methodical with their demolition plan. The last building they kept standing and operating was a pub so the construction workers had somewhere to drink. The Railroad company did not pay relocation expenses.

Today, as plans are put forth for the redevelopment of the area surrounding Penn Station, buildings in the neighborhood are once again at risk of demolition. Under the current redevelopment plan, first put forth under former governor Andrew Cuomo as the Empire Station Complex Project, several landmarked eligible buildings would be sacrificed to make way for 10 new office towers. That plan has since been given a new name under Governor Hochul, the Pennsylvania Station Area Civic and Land Use Improvement Project. In recent months, support for the plan has waned and developer Vornado has said their work on the project is currently paused. Meanwhile, those who support alternative visions for the future of Penn Station have put forth some intriguing renderings.

Discover hidden remnants of old Penn Station and explore a new train hall inside a historic Post Office building!

Before Pennsylvania Station opened in 1910, passengers traveling on the Pennsylvania Railroad from points west were not able to cross the Hudson River. All passengers had to disembark from their trains in Jersey City.

In Jersey City, at a terminal site now occupied by the Exchange Place PATH station, travelers would board ferries to get them across the river to Manhattan. Once on the New York side, they would alight at the Cortlandt Street ferry station and travel on to their final destinations.

The former Penn Station covered two city blocks and 8 acres of land, making it the largest indoor public space in the world when it opened. The massive structure featured grand Classical architectural elements like long collonades and large arched windows.

In 1929, an air-rail service was launched between New York City and Los Angeles, whereby passengers could take a train to Columbus, Ohio, fly from there to Waynoka, Oklahoma, train to Clovis, New Mexico, and fly from there to Los Angeles.

The Pennsylvania Railroad partnered with the Santa Fe railroad and Transcontinental Air Transport, Inc. to offer this passenger service and enlisted a number of celebrities to inaugurate it, including Charles Lindbergh, Gloria Swanson, and Mary Pickford. According to Lorraine Diehl in The Late Great Pennsylvania Station, in New York City, Amelia Earhart broke a bottle of champagne on the propeller of a Ford trimotor airplane displayed in the main waiting room of Pennsylvania Station. She led the first 19 passengers to the train for the first leg of their cross country journey. It has been said that the plane couldn’t fit in the entrances so it had to be disassembled and then reassembled inside the waiting room.

The original station contained many corridors that once connected it to nearby destinations such as the New Yorker Hotel and other subway stations. The most famous of these lost passageways was the Gimbels Passageway which stretched out over 800 feet under 33rd Street, connecting Penn Station’s 7th Avenue subway lines to the 6th Avenue lines accessible at the Herald Square Station under the former Gimbels Department Store.

The Hilton Passageway, which still exists in part, used to connect the 1,2,3 trains in Penn Station to the Hotel Pennsylvania. Today, it serves as a corridor that connects the lower Amtrak concourse, the Long Island Rail Road, and New Jersey Transit to the 1,2,3 trains. It is now blocked off by bricks – you can see the original opening by the change in white bricks along the wall. Over the course of renovations, another passageway was revealed which once led from the LIRR concourse to IRT or the 1,2, and 3 trains as they are known today. Boarded up in the 1980s, the passageway featured Guastavino tile.

The former Penn Station was the first train station to allocate separate concourses for arriving and departing passengers. This innovation helped control the flow of traffic to the station’s 11 platforms which served 21 tracks.

Pennsylvania Station was really just one piece of a larger $114 million (approximately $2.5 billion in today’s money) puzzle that included a new right-of-way from Newark to Manhattan, bridges, tunnels underneath the Hudson and East Rivers, and a new rail yard in Queens. At its peak of operation in the 1920s, Pennsylvania Railroad boasted 28,000 miles of track and 279,000 employees.

At the same time, it was running 6,700 trains a day transporting fully 10 percent of all freight in America, and 20 percent of all passengers. Still the scope of Penn Station is staggering: roughly 550,000 cubic feet of stone, 27,000 tons of steel, and 15 million bricks were used during construction of Penn Station

Pennsylvania Station, although looking much older, was only 53 years old when its demolition commenced in 1963. The glass ceiling had been painted over for safety during World War II and was never undone, lending to the perception of a station in decline.

The once bright facade and interior spaces were clouded over by soot. Penn Station’s demolition was precipitated by the bankruptcy of the Pennsylvania Railroad company, which was forced to sell its air rights.

Passengers continued to weave in and out of Penn Station even during its demolition. Not one day of travel was disrupted during this phase. In order for train service to continue uninterrupted, a steel deck was built over the platforms and tracks, which were below street level.

As demolition continued overhead, various structural and non-structural pieces remained in the areas below. Which leads to our next secret…

Staircases, handrails, a stunning cast-iron partition, glass bricks that once formed the floor and ceiling of the original station, two eagles (of the many that have found new homes around the country) and many more remnants of the original Penn Station are still located in the subterranean replacement. You can track them down on our Remnants of Penn Station walking tour.

New renovations at the station have obscured some of the remnants that were once visible, but the renovations have also paid homage to the original station. A new mosaic mural at one of the station’s accessible entrances depicts the iconic clock from the original station.

The original coal-fired power plant of the station, built as a mirror image using the same Tennessee granite as the lost Stanford White masterpiece, still exists on 31st Street. Today, the power plant is in a significant state of disrepair, with broken windows.

When it was in operation, the powerhouse building generated electricity to power the station, provided heat, light, elevator hydraulics, refrigeration, and even incinerated garbage. By 1989, the power plant on 31st Street was almost completely obsolete. Check out photos of the obsolete equipment inside the power house here!

Next, see more photos of the demolition, photos of the station in its heyday!

Subscribe to our newsletter