NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

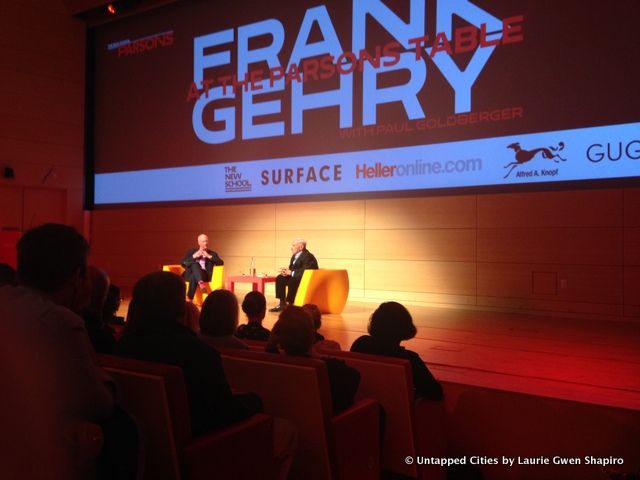

The line started near 63 Fifth Avenue and snaked east around 14th Street as far as the eye could see. The miserable souls at the end were rightly panicking that they wouldn’t get in. A passerby wanted to know: Was there a rock star in town? No, a tall man in well-designed glasses stopped to explain. “A starchitect.”

“A what?” And then after a short explanation, an incredulous follow-up: “An architect is causing this kind of line?”

Yes, and not just any starchitect, the masses were here to have a live encounter with perhaps the greatest living starchitect of them all, Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Frank Gehry.

The 86-year-old living legend is the subject of a new book by no slouch himself, the former The New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, a 64-year-old who also holds the Joseph Urban Chair in Design and Architecture at The New School/Parsons School of Design. So it was no accident that Goldberger had arranged for his friend Gehry to join him for his first New York appearance to promote the book, Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry. Two large auditoriums were used for the considerable overflow, and a veritable Who’s Who from the architecture and design worlds filled the VIP seats near the press seats.

As necks craned to see who had made it in the auditorium where Gehry would actually enter, in walked Candace Bergen.

David E. Van Zandt became The New School’s president in 2011, and one wondered if his Gehry introduction was a career highlight. He thanked the sponsors, including Heller, the firm that produced the Gehry-designed neon orange plastic chairs on stage. A minute later Van Zandt beamed as Gehry and Goldberger walked on stage to loud applause, architecture royalty.

The first really interesting question was on Downtown’s new pride and joy, better loved than One World Trade Center (which Goldberger and Untapped Cities founder Michelle Young discussed at length together on HuffPostLive earlier this year): the sleek and inspiring New York by Gehry apartment building at 8 Spruce Street. Goldberger asked, “How did you deal with the New Yorkness of it? You were dealing with a New York skyscraper for the first time, a couple of blocks away from the Woolworth Building, and in the context of an iconic skyline—”

“Everyone thinks of the Woolworth [Building] as a pretty important piece of architecture from the past and some of the buildings around it were, frankly, disrespectful. And 8 Spruce was going to be the first one that was parallel and close to it. So I started to look at the Woolworth Building, the terra cotta décor, the scale, the roof. [Because of its roof] “everyone thought I should put a hat on it, but I thought putting a hat on top (of 8 Spruce) was detrimental to the persona of the Woolworth Building.”

“You mean, let that be the only one with a hat,” Goldberger said.

“Right. The scale of the fabric form that I created is in the scale of the terra cotta – those forms are bay windows, but they are not decoration, they added value.”

View of Woolworth Building from New York by Gehry

Gehry then spoke of people he would not name who specialized in speculative apartments, and confessed he used them to speed the project along with a baseline. “What came back though looked stubby against the Woolworth. To add ten floors would be 50 or 60 million extra.” A significant sum. “But Bruce Ratner has an architectural conscience and he was convinced.”

Gehry found no shame in using a proforma floor plan. “We do not try to reinvent every aspect – we would look for efficiency. These were rentals not condos like on 57th Street. You take the jobs with the baggage that comes with it.” He later added, “Hopefully your client is willing to step into the game and push those limits. That’s all you can ask for.”

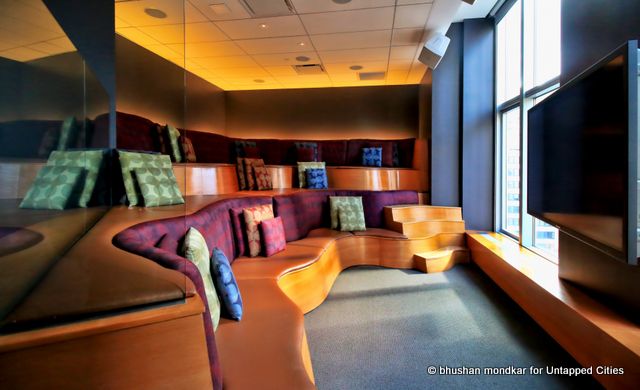

Interior space at New York by Gehry

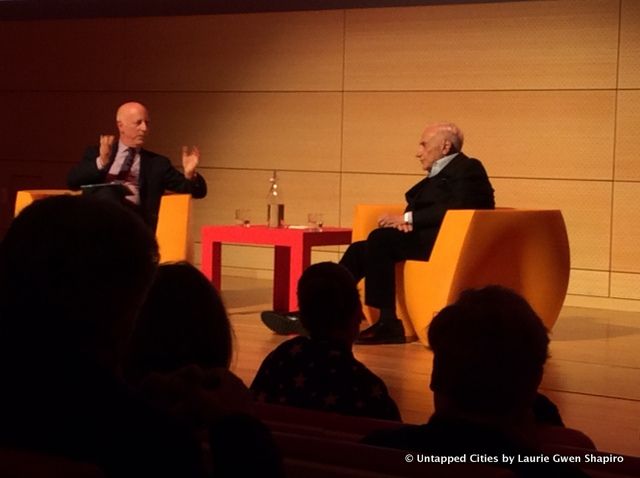

Things were about to get really interesting. Gehry kept referring to his method as play, and when Goldberger continued to use the word design, he had enough. “I don’t like the word design – take it away.”

“Maybe we should change the name here to the Parsons School of Play,” Goldberger quipped, and Gehry laughed.

Paul Goldberger, left, Frank Gehry, right

The starchitect lamented that his profession holds such a low place in the minds of art historians, hinting that functionality is a dirty word. “Look, the tradition of architecture is from way back – it was an art. How (architecture) got screwed and put to the bottom of the list I don’t know. The ancient library in Florence is one of the greatest works of art and yet works as a library. Look I’m happy to just be a stupid architect. Design has other connotations.”

After the laughter died down, Gehry dove into his new futuristic Facebook campus in Silicon Valley’s Menlo Park, explaining it was utilitarian in execution but still successful and pushing boundaries. “You can build a better building with the same amount of money. That’s what I’ve been trying to say with my work. If you can build for x (dollars), why not try to build something more delightful, more engaging, that has a mystery or you can learn something from? Something that has a history. Something to remember. Something that develops your visual intellect. If you are in a building it should be a place you like to be in – if it is a house, you want a place that makes you feel good and is a place you would like to think about every day.”

He stopped for a second to readjust into a more comfortable position. “I think we can make this stage a little more comfortable. I hope the guy who designed the chairs isn’t here.”

Goldberger suggested that they talk about “that building in Spain.”

Guggenheim Bilbao Museum in Spain

“[What] we were able to do in Bilbao had such an incredible economic impact – that it changed the culture, it changed the politics, the ideas. I had no idea you could do that. When I went there in the early ’90s it was a dead on arrival city. People tried to get out of it as fast as possible. The shipping and steel industry was gone. When I started working there they published a Fatwa – kill the American architect.”

“And it turned around, and it was 300 bucks a square foot. It didn’t take that much to have impact – now the city has earned $3.5 billion since the building has opened. The amount of change is amazing. I’m so stupid that I don’t live there, because I could live there for free and I would get all the love I need.”

Richard Serra inside Guggenheim Bilbao

When the audience positively guffawed this time, he reconsidered. “I think I am going to move there.”

“You did go there to celebrate your 85th birthday not long ago,” Goldberger said. “But if you leave there then you’d be leaving Los Angeles where you’ve been now for 67 or 68 years?”

“Wow, that’s a long time,” Gehry said.

“It is a city you are identified with I would say as completely as Christopher Wren with London or Stanford White for New York. Perhaps you were discouraged [when] Disney Hall ran into trouble, and suspended construction for a period.” Goldberger recalled how Gehry had told him he had considered moving at that point. “You felt like a pariah in Los Angeles. But now you are a big guy and a big hero.”

“Yeah!” Gehry said ironically. “That’s true! Even the mayor—“

Goldberger finished his line. “Even the mayor likes you. And the mayor gave you the Los Angeles River to work on.”

“I know that you are sensitive that your work is just these crazy shapes,” Goldberger said, explaining that earlier in the day they were at a television studio and there was a sculpture of some “bloblike thing.” As they had walked past it Gehry had muttered, “They are going to think I designed it.”

“What do you make of that perception or misperception?” Goldberger prodded. “It seems to me that the notion that everything you do is weird goes along with the notion that everything you do is too expensive.”

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles

“I don’t know about weird. It’s comfortable. I think in regard to the (Disney) concert hall people like going there. It’s a real people place. It solves a problem.” He looked around the room. “That hasn’t been completely solved here in this room. When you go into Disney Hall and sit down and the orchestra comes on stage, the relationship between the players and the audience is really strong and the orchestra feels the audience. When [the audience] likes what they are playing, they play better. And the audience likes it better. It’s a win-win. For the twelve years that they’ve been playing there, they’ve gotten better. It’s phenomenal. They tell me this, but I feel it.”

“It is an extraordinary building,” Goldberger said.

“The relationship between audience. I don’t feel it here. I wish I did. Maybe I’m unfairly comparing it to Disney Hall.”

Walt Disney Concert Hall stage, photo via Discover Los Angeles

Goldberger looked more than a little uncomfortable, the lecture was being sponsored in the New School after all. “Well, it was definitely not designed for the same concept or program.”

“That’s true,” Gehry conceded, and went on. “There is a feeling there in (the Disney Hall) and I was aware of it. The client was asking for a 2,500-seat hall and I built models of a 2,500-seat hall, small models, but you see that it wasn’t achieving that intimacy. So I convinced the client to let me explore doing a 2,200-seat hall and we did a model of that. And you felt it. So then I could move, I could add seats, I could squeeze seats in to 2,200 and build it up.” He stopped to think. “2,385 almost 2,400. And everybody could see the difference. And feel the difference.”

Goldberger asked, “Do you think that once a building is done and used for a while that it no longer fully belongs to you?”

“Oh yeah, I think so, yeah. Certainly Bilbao. [It] had so many shows where the artists were not fans of mine, and they would call me. The best one was Cy Twombly. He called me, and said I was told never to show in this place and this is the best effing show I’ve ever had – and then he died.”

“But he probably died happy,” Goldberger quipped.

“The rap on Bilbao was that it was more about the architecture and not about the art – and that’s not what the artists are saying. That was what art museum directors said. But after Bilbao, it got a lot of accolades, but I never got hired for another art museum. It was the rap.”

“Do you ever get stuck and how do you get unstuck?”

“I always get stuck and I don’t know where I’m going with it. I’m looking for something that I don’t now what it is. I don’t think it is bad to repeat yourself. There are a lot of architects with repeatable language. 3 am is when I wake up and I have a nightmare – and I feel like someone else.”

Goldberger interrupted his guest to quote F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Crack Up: “In a real dark night of the soul, it is always three o’clock in the morning, day after day.”

Gehry nodded, and admitted he grappled with the “Beekman Tower” (the original name for New York by Gehry). “I was trying to play with the folds, I was fascinated with the folds.” He thought of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s folds and Michelangelo’s folds. “It was a 3 am thing. I have nightmares about not being able to do it. Finish. I value the insecurity of (fear) because I know that I’m getting there. By now I’m used to that insecurity. But I do know when to stop. This sounds like it goes on for five years. It’s not mystical.”

An index card came from the audience, read by Goldberger: “Of all the buildings you’ve made, which do you feel you learned the most from?”

Gehry paused long, then answered: “I think the house I live in now. (In Los Angeles.) This first house made me realize how little we needed to cross the line. You don’t have to invent new technology. It’s fun to invent new technology but it’s not the ‘only.’ It’s a lot simpler this other way, it’s just asking a lot of questions.”

This naturally segued into a discussion of where he may have inherited his taste for curiosity. He was born Frank Owen Goldberg in 1929 to Irwin and Thelma Goldberg, and Gehry channeled his Polish Jewish roots for the discussion. “I think of things my grandfather told me. I think of old guys sitting around a table and arguing what Rabbi Hillel said. [Talmud scholars] sit there for hours and days and weeks even – if you go to Israel you see it – they sit at a table. So I grew up with some of that – and the Talmud starts with the word why.”

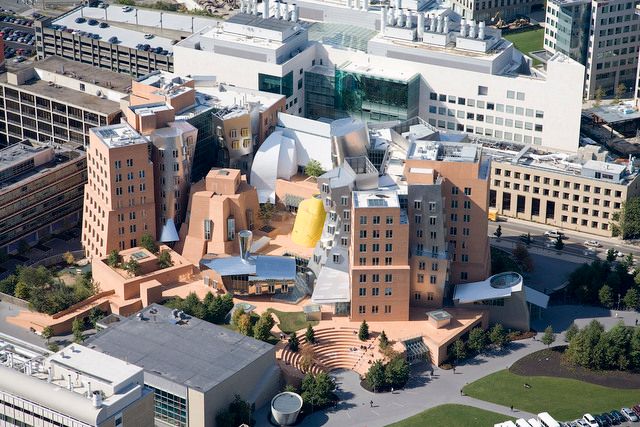

MIT Stata Center. Photo via Wired New York.

On the controversial building at MIT, the Stata Center, which Goldberger delicately said had a more “complex” reaction.” (For starters, MIT sued…)

“I thought everyone loved it,” Gehry said dryly, eventually adding, “Although Noam Chomsky didn’t like it. He was in Building 20 that had been torn down, and had a lot of space in that building [including] his library. For just an ordinary professor type he had a lot of stuff. He liked that you couldn’t lock the windows and he loved that the squirrels came in. When Chomsky complained to me about this, the building was already built, and he had already picked his new office on the sixth floor, and I said, ‘Well, I’ll design a squirrel ladder for you.'” After considerable laughter in the room, Gehry added, “I haven’t talked to him since.”

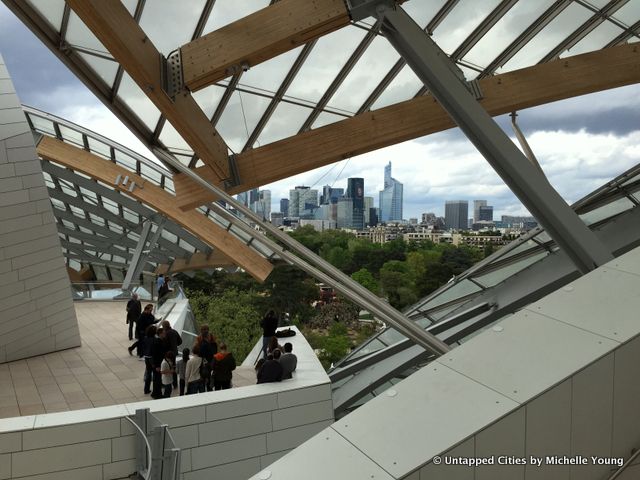

What was the inspiration for one of his latest building in France, the Fondation Louis Vuitton, which opened fall of 2014 in the Bois de Boulogne?

“I’m still trying to figure that out! When I was taken to the site, I realized Proust must have played here as a child and it brought tears to my eyes. The history of that site!” Gehry wanted to build with glass in a park, citing London’s Crystal Palace as inspiration. He discussed the glass inspiration with those who had to give approval and they liked that idea. “The problem with that though is that you can’t hang paintings on glass. So once we got approved to go higher we then had to build a building – so it became two buildings – very expensive kind of thing. But I liked the idea of having art between glass and a solid building. I’m a sailor – so [the glass] became sails – it is a full regatta in the park.”

Asked what kind of new hire he seeks, Gehry sheepishly admitted, “I don’t actually hire anyone so I don’t know.”

Paul Goldberger smirked. “What do you tell the people that tell the people that tell the people to hire what to look for?”

Gehry laughed. “I occasionally teach at Yale and usually there is a student or someone there who I like and I’ll invite to join the company.” “Some have gone on to be partners,” his venerable biographer said knowingly.

“But others have too,” Gehry said defensively. “I think there’s a fair shot for all. There’s a (mandatory) two-year period of making models. And watching the process of work. We’ve tried to go faster but that doesn’t work.”

Among people who work closest for him, he seeks individuals who are, “fairly intelligent, and can have a dialogue, who I enjoy working with.” He wants a colleague willing to play along, and one that sometimes even ventures forth with ideas of his or her own. “I don’t like working alone. I like working in a team. The only hard part of that is when my insecurities flare, people don’t always understand why I’m pacing back and forth. All I know is that architecture is being realistic about budget and time, and knowing you have to stop. That works.”

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Frank Gehry’s New York by Gehry building and the Gehry projects never completed in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter