Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

If you close your eyes and picture Long Island’s suburbia, the neatly manufactured streets of Levittown often spring to mind – the manicured lawns, freshly smoothed sidewalks, and neat little cape homes flanking the broad, gently curved streets. For many, this was their Long Island – created during the post World War II era of optimism, and has become the narrative that Long Island, comprised of Nassau and Suffolk Counties, countless villages and unincorporated hamlets that are home to 2.8 million people, has most been anchored to.

What is often overlooked is the fact that Long Island was settled long before Levittown – in fact, areas of European settlement on the Island are so old they predate the United States of America by a century or more. From the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century, Long Island witnessed growth that modeled itself after the preplanned garden cities of Europe. The book Gardens of Eden: Long Island’s Early Twentieth Century Planned Communities, a collection of essays edited by Robert MacKay for W.W. Norton & Company, explores some of the more unique areas in the region.

Over the decades, these areas, especially in Nassau County, were sought-after by ambitious developers for not only their exclusivity, but proximity to New York City as well. Developers also sought the rural isolation of Suffolk County, which had less than 100,000 people in 1910.

When one examines the areas explored in the book, certain themes arise. The ambitions of man to shape the natural environment, the desire to blend the benefits of both urban and country living, as well as the importance of the old doctrine of real estate – location, location, location.

Using Gardens of Eden as a guide, the following five communities are unique stops along the region’s rich and varied history, helping to shape the Long Island its residents know today.

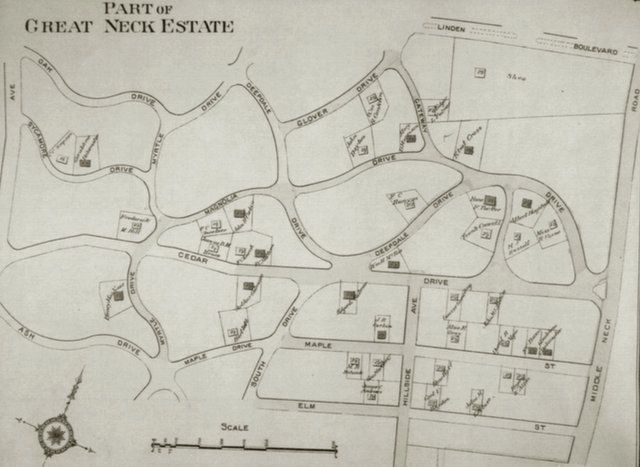

The E. Belcher Hyde Atlas of Nassau County, 1914, shows the new 450-acre Great Neck Estates between Little Neck Bay and Middle Neck Road. Courtesy Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities

At the time, Harvey Stewart McKnight’s grand 450-acre vision for Great Neck was the largest real estate project to be undertaken on Long Island. Stretching from Little Neck Bay to Middle Neck Road, one of the main arterial routes for the peninsula, the development caught the imagination of buyers and helped launch the first, if not short-lived, real estate boom in Nassau County. The project included an open competition in 1909 to solicit the most creative landscape designs, awarding a young planner $1,000 for his effort modeled after English Country Estates of old. Between Harvey’s ambitions and the collective backing of his five brothers who formed the McKnight Realty Company, Great Neck Estates eventually grew into what was called by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle a ” center of wealth and social influence.”

The project was massive in scope – lots ranged in size from 20 x 100 to 110 x 100, included 26-miles of winding country lanes, and was designed so each house had a great view, including many with waterfront vistas.

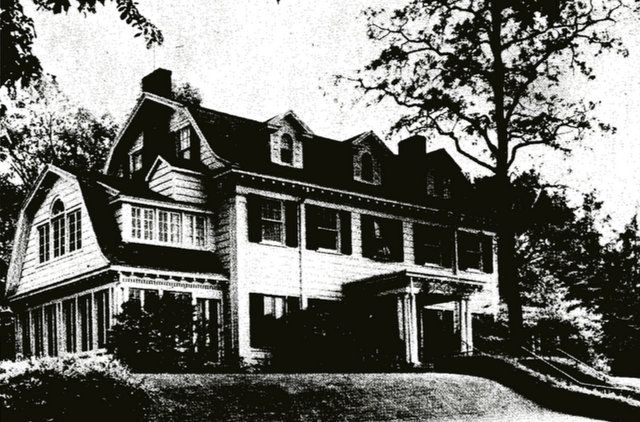

This handsome, two-and-a-half- story gambrel-roofed Dutch Colonial was photographed with its trim yard and spindly young trees in 1913. It is now the site

of the Village of Great Neck Estates village hall. Courtesy Village of Great Neck EstatesMore than just a homebuilder with prime developable land, McKnight was a visionary who saw the potential benefits of expanding the area’s commuter infrastructure. An active proponent of the LIRR’s East River Tunnels and electrification of the LIRR’s Port Washington Branch, McKnight knew that all of Nassau County would benefit from increased and speedier accessibility to New York City.

A shrewd political operative, McKnight knew the importance of home rule. To protect both the character and future of his development (and to prevent annexation into New York City, which McKnight feared was next for Nassau County), McKnight advocated for residents to incorporate as a village – on April 16, 1911, the Village of Great Neck Estates was born. By 1922, there were 150 houses in the village. Today, roughly 2,700 call the area home, and continue to build and thrive in the area.

Belle Terre Estates’ entrance lodge was designed by John J. Petit of Kirby, Petit & Green. Photo via Kenneth Brady, Village of Port Jefferson historian

Located on the hilly North Shore of Suffolk County in Port Jefferson, 62 miles east of Midtown Manhattan, Dean Alvord’s Belle Terre Estates was just one out of many projects the developer undertook, with his scope of work spanning anywhere from the City of Rochester in Upstate New York to the Town of Southampton on Long Island’s East End.

An enclave of wealth carved into the glacial hills of Long Island’s North Shore, Belle Terre was not for the urban commuter like his other projects Prospect Park South and Roslyn Estates, but rather, “an ideal spot for a summer house, be it a palatial estate or modest bungalow.”

Port Jefferson Station of Long Island Railroad. Photo via Kenneth Brady, Village of Port Jefferson historian.

Alvord purchased the entire 1,600 acre peninsula, including controversially, the water rights from the Town of Brookhaven, looking to capture the bucolic charm of the five miles of waterfront the geography provided. Like McKnight, Alvord saw opportunity with the LIRR – so much so he donated the land for the handsome still-standing station house for the Long Island Railroad’s Port Jefferson stop to serve residents of Belle Terre, roughly one mile away. (Never mind the fact that Alvord, and his good friend Ralph Peters who was president of the LIRR, both were building their own houses at Belle Terre).

The development grew as more of New York’s titans of industry caught wind of the project. By 1917, 48 residences were constructed on the peninsula. The project included stately landscaping and recreational spaces along the wind scarred bluffs of the peninsula. As time wore on, many of the extravagances of Belle Terre were demolished, and the famed Belle Terre social club burned down. In the 1930s, the Village, like so many planned communities on Long Island, sought to cling to their exclusivity by incorporating.

Still, the charm of the development remains – Belle Terre is considered by many to be one of the most exclusive residential enclaves on Long Island, and MacKay writes that Alvord “did perhaps more than anyone else to establish the standards and appearance of suburban development on Long Island at the outset of the twentieth century.”

Planted medians, red

tile roofs, and red brick streets set the tone in Long Beach. Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities.Long Beach, in what became one of Long Island’s two incorporated cities, was the idea of Senator William H. Reynolds, a developer with a strong track record who constructed thousands of houses and apartment buildings and Brooklyn and Queens. In 1906, Reynolds, like so many other developers of the era, encountered a “a blank tract of land” with “so many hundred feet waterfront” that offered “carte blanche”. It is here that Long Beach rose, and created what many called a “new city by the sea” within the ideal suburban environment Long Island offered.

The concept was to build Long Beach as the region’s answer to Atlantic City, targeted exclusively for what he deemed to be the “wealthy classes.”Long Beach was to be even better than Atlantic City, for it was located even closer to New York City. By 1907, the Brooklyn Eagle already deemed Reynold’s project a success, with the “Estates of Long Beach” opening to a crowd of at least one thousand people. The crowds, like many of the planned communities of the era, were made possible thanks to the prospect of sizable investment by the LIRR, who had plans for one of their “finest depots” that ensured the all-important 30 to 40 minute ride to Manhattan.

Hotel Nassau on the boardwalk. Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities

As time wore on, Long Beach built more hotels, casinos and invested heavily in their bathing facilities, which could at the time accommodate up to 5,000 bathers. The Eagle heaped praise upon Reynold’s accomplishment, with the publication speculating that the City by the Sea’s popularity will span the globe. By design, Long Beach was to capture the essence of the best seaside resorts, as well as emulating Reynold’s residential developments in Laurelton, Queens.

Today, Long Beach retains much of the charm and character since its founding – with its future up still being shaped by ambitious prospective development, as well as the challenges mother nature throws at its waterfront, the City’s main spirit is derived from its residents, many of whom are lifelong inhabitants of Reynold’s City by the Sea.

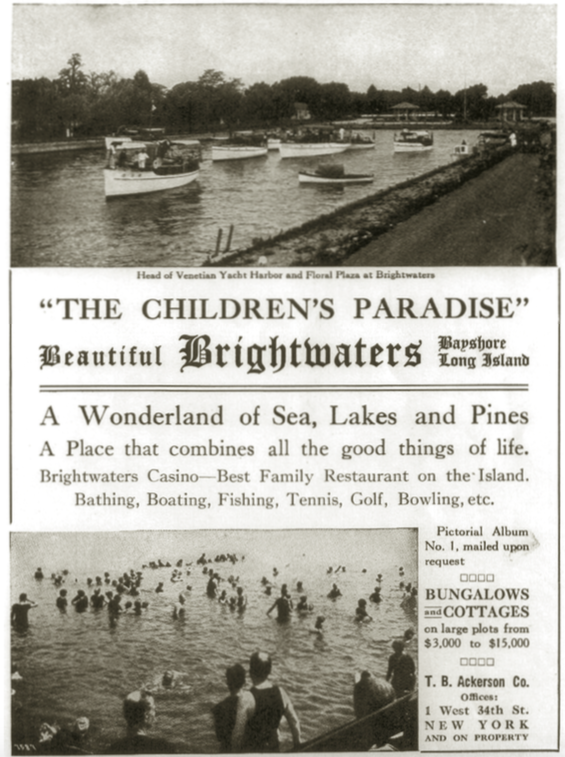

Bathing pavilion at the entrance to the Venetian Canal, ca. 1910. Bay Shore Historical Society

T.B. Ackerson’s grand vision for the South Shore of Long Island, started as a $500,000 purchase of 525 acres of land from the Charles E. Phelps estate in 1907. Ackerson quickly supplemented his purchase with other large tracts of land, totaling 1,300 acres for his eventual “Thousand-Acre City by the Sea.” The project stretched the wide expanse of the Great South Bay north to the LIRR tracks, where 400 acres were set aside for experimental farms that showcased an area’s fertility – an effort to attract more residents.

Ackerson’s vision varied from that of Long Beach – Brightwaters was to be a “an all-year home colony instead of a summer stopping place.” Like many before him, Ackerson knew the role easy accessibility would have to this project’s success – the newly completed East River tunnels, and ease of commuting to New York City from the development became the focal point of the Ackerson Company’s promotional materials.

The key concept of the project was emulating Venice. Ackerson, not one to be tamed by natural geographic layout, uprooted the existing pitch pine forests in the area (a small slice can still be found to this day within the Edgewood Preserve in Brentwood) carved lakes, and converted the salt marshes into a 175 foot wide, 20 foot deep grand canal that took two years to build from 1908 to 1910, and at the time cost upwards of $250,000.

Along with the grand canal, Ackerson created parks, forty miles of wide, planted streets, water and gas mains and electric street lighting. For homes, lot sizes were typically 100 x 150 feet, and Ackerson offered four simple models for his customers to choose from. If none sufficed, he was happy to just sell off the land and allow future residents to bring their own builders. By 1917, Ackerson built 200 homes, making Brightwaters one of the “most successful planned suburban developments of the period.”

Ackerson Company advertisement featuring water recreation. From a Long Island Railroad booklet, ca. 1917

Soon, a 620 acre section of the development stretching from the Bay to the LIRR tracks incorporated as a village, and Ackerson’s dominance over the project began to wane. Paired with downturn in development following the outbreak of World War I, Ackerson eventually auctioned off his land for a loss, leading him to the path of bankruptcy in 1920. Despite bankruptcy, Ackerson paid his debts and attempted a new project in Roslyn, before suddenly dying.

His legacy lives on. In 2007, Brightwaters celebrated its centennial with two-thirds of the village’s Ackerson-era structures still standing, and landscape remaining period correct. Ackerson’s vision still benefits residents today, and will continue to do so in the coming decades.

Timothy Woodruff house on Stewart Avenue, ca.1908. Village of Garden City, NY, Archives Collection

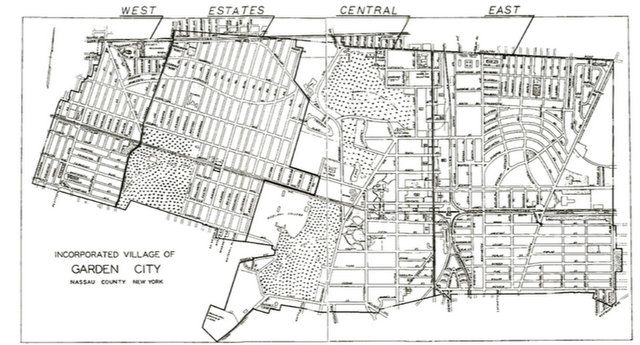

Few communities capture the charm and long lasting endearment of Long Island’s early planned communities like Nassau County’s Garden City. Founded by department store tycoon A.T. Stewart in 1869, the City evolved from its first master plan in 1870 through the 1920s. Early praise of the community focused on the urban design, including the 45,000 trees that lined the city’s roads and architecture stylings of the grand homes within the area. Soon, Garden City was compared to the “Eden of Long Island.”

Stewart, and his friend John Kellum, a local Hempstead-raised architect, set out to plan a new community from the ground up on the 7,170 acres purchased from the Town of Hempstead for $394,350. The site was ideal for Stewart’s vision, fitting his criteria of being located within 12 miles of New York City. The project drew immediate attention, with Harpers Weekly stating “Hempstead Plains, hitherto a desert, will be made to blossom as the rose.”

Brick Disciple house, ca.1875, John Kellum, architect. Village of Garden City, NY, Archives Collection

The city continued to evolve and adapt to the changing visions of the American ideal – from space that emulated the grand garden cities that dot the English countryside, to a religious center of learning and spirituality, to a place that showcased the excessive wealth and prosperity American industry provided at the height of the 1920s.

Garden City’s first railroad station and post office, ca. 1873. Village of Garden City, NY, Archives Collection

For a time, Garden City’s identity was as fleeting as the ever-shifting American ideal of utopia – and few areas of Long Island encapsulated the quick evolution of the concept as A.T. Stewart’s vision. Today, the City remains one of the most unique areas in the region – and like it’s history suggests, is always evolving.

From struggles over how to preserve its historic identity, to how to retool itself for the challenges presented by 21st century living, Garden City encapsulates Long Island as a whole. How does suburbia evolve itself to remain relevant to the times, all while paying homage to the area’s heritage and serving the needs of its residents?

As a whole, Long Island’s communities, planned, and in so many cases, not planned enough, face this struggle. With environmental constraints, rising costs, declining municipal revenues, aging infrastructure and political divisions, many look back at the areas examined by MacKay in Gardens of Eden: Long Island’s Early Twentieth Century Planned Communities with a whimsical nostalgia.

Today, the story is still the same. Ambitious developers see Long Island’s relative openness, standing in stark contrast with New York City’s density, and see both potential and moneymaking opportunity. In the past, these developers faced little resistance to achieving their goals. Today, residents work to protect their own slice of the suburban ideal that the Nassau/Suffolk region offers.

From Great Neck Estates, Belle Terre, Long Beach, Brightwaters to Garden City, policymakers and the constituents they serve can both learn and apply the lessons learned from these great suburban experiments – one of which is, without a dedicated vision, we all flounder.

Next, check out a very different type of Long Island suburb: a former Nazi Neighborhood and camp.

Rich Murdocco writes on land use and development issues, with his work regularly appearing in Newsday, Long Island Business News, New Geography, and a weekly column for the Long Island Press. He has his BA from Fordham University in both Political Science and Urban Studies, and his MA from SUNY Stony Brook, where he studied regional, environmental and transportation planning with Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran planner.

You can view his collection of published work at his website, www.TheFoggiestIdea.org, follow him on Twitter @TheFoggiestIdea, and LIKE The Foggiest Idea on Facebook.

He is a lifelong Long Islander, and lives in Nassau County with his wife Arielle, and dog, George.

Subscribe to our newsletter