New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

Last month, we shared with you a curator walkthrough of the fascinating exhibit, Jacob Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half at the Museum of the City of New York. Here are 10 highlights of the exhibit that showcase the breadth of the installation and demonstrate how reformer Jacob A. Riis was much more than just his photographic legacy.

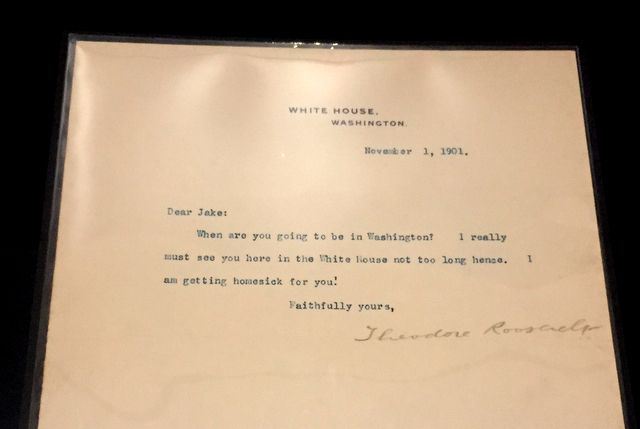

Teddy Roosevelt and Jacob Riis became close friends during Roosevelt’s tenure as New York City Police commissioner. Curator Bonnie Yochelson calls their friendship a “bromance,” telling us “The two men supported each other publicly, artfully using the media to enhance each other’s reputation.” The original letters displayed in the exhibition reveal the chumminess between the two. In the above, written on White House stationery in 1901, Roosevelt refers to Riis as “Jake” and asks when he will visit Washington: “I am getting homesick for you!” Roosevelt writes.

Another letter, on Civil Service Commission letterhead from 1894 is much longer (and begins more formally). “Dear Sir,” it reads, “Unfortunately I had to leave New York before being able to get down to see you again. I am very sorry, and I shall hunt you up the next time I come to New York.” Roosevelt expresses his desire to introduce Riis to New York City mayor-elect William Strong, the anti-Tammany Hall candidate who Roosevelt feels is a “working man’s mayor.” He praises Riis’ efforts: “I know barely any one who has done more than you to give people an intelligent appreciation of the great social problems of the day and who has approached these problems with more common sense and sobriety.”

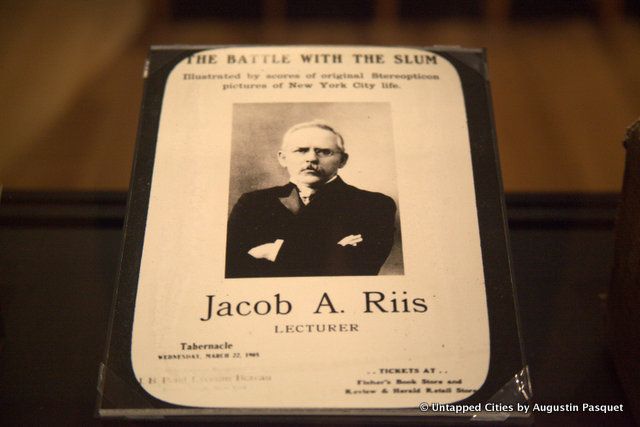

Two cases in the exhibit display some of the early editions of Jacob Riis’ many books. The first, located in the entrance hallway contains his earlier publications like The Battle with the Slum and How the Other Half Lives. The second display case shows later publications from after 1900 including Children of the Tenements and Out of Mulberry Street.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a large map that geolocates where Riis and his team were photographing conditions in Manhattan. These include many downtown spots like Chinatown, Lower East Side, Newspaper Row by City Hall but also some places further uptown like Hell’s Kitchen.

Around the map and on the wall are prints from the Museum of City of New York’s collection of Jacob Riis photographs. Some the collection are original but most are reprints using Riis’ negatives and produced in the methods available during Riis’ life. Chicago Albumen Works handled the project, using sunlight to develop the images. While these images are likely the reason why many visitors will go visit the exhibition Jacob Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half, it is just one of the many highlights you’ll discover.

In the back of the exhibit is a projection of one of Riis’ traveling lectures (along with a lantern slide projector from the time period), entitled “How the Other Half Lives and Dies in New York.” The voiceover is derived directly from a script found in one of Riis’ notebooks and narrated by Terry Borton of the American Magic- Lantern Theater. The music that plays in the slideshow, the hymn “Because He Loved Me So” is mentioned in the notebook and the images were matched up by Yochelson from Riis’ notes.

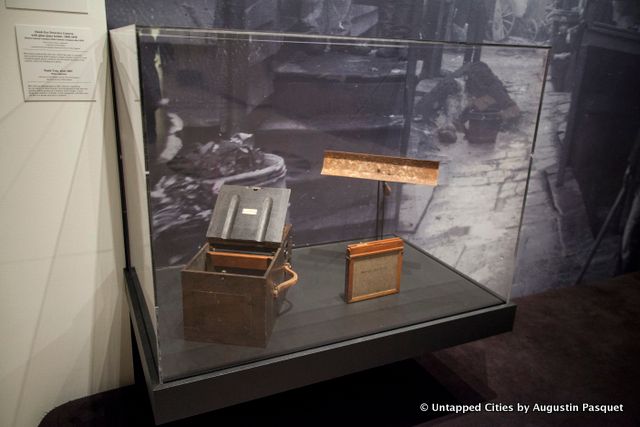

This 1888-1898 Hawk-Eye Detective Camera made by the Boston Camera Company is similar to the camera Riis and his team would have used. As described in the exhibition, the camera “easy to operate and could be hand-held without a tripod. The camera could hold glass plates inside the back of the camera.” The object next to the camera is a Flash Tray. The trough held flash powder, which when used for photography created a big flash of light, a loud sound and sparks. As the exhibit states, “It was dangerous, and Riis twice set fire to a house and once to himself.”

Five Cents a Spot, photo by Jacob A. Riis. Image via Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Roger William Riis

“Five Cents a Spot” maybe one of Riis’ most indelible images. The title of the photograph may seem obscure today, but in the day it would have immediately denoted that the place shown was an illegal lodging house. Five cents refers to the rate of the bed, which was set at a minimum of 7 cents then. Moreover, the number of people in this space could not even be captured by the full frame of the photograph – there were more than 15 here, most of which slept on the floor.

Yochelson says, “This is a typical flash photo, where there is essentially no light in this room. [Riis] barges in, takes a picture with the flash, scares the living daylights out of the people – you can see it in their faces – the flash actually makes a burst of light and a boom – so it’s terrifying. Those were the first pictures.”

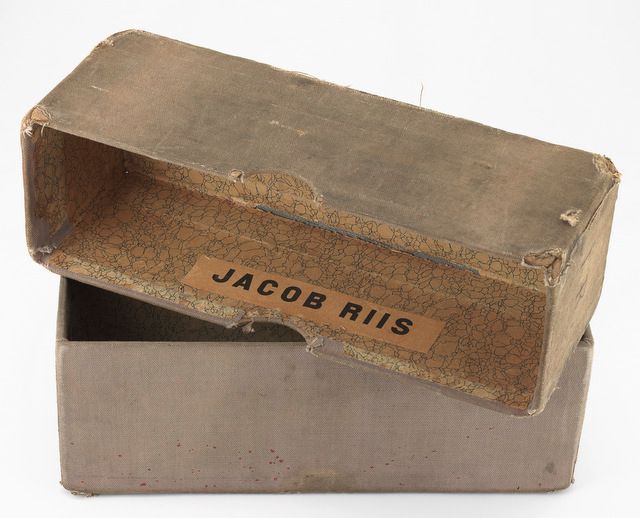

Jacob Riis died in 1914, but his photographic collection was only discovered in the 1940s in the attic of Riis’ home in Richmond Hill, Queens. With this exhibition, Yochelson hopes to reposition the narrative around Riis, which in the recent period has focused on the photographs left behind. Riis himself did not put particular stock in the images, apart from being a tool for his larger social reform initiatives, and left the collection behind himself when he moved.

In the 1940s, Riis’ son, Roger Williams Riis, was encouraged by the fine art photographer Alexander Alland to return to the house to retrieve the collection, which contained negatives, lantern slides, and prints. Roger Riis donated it to the Museum of the City of New York, and a subsequent exhibition at the museum would come to define Riis’ legacy – as a fine art photographer. Yochelson tells us, Alland “brought Riis to public attention as a photographer with a show at the Museum of the City of New York in 1948 by taking Riis’ negatives and making beautiful prints. He kind of twisted our idea of Riis as a photographer to a mid-20th century idea of what a photographer is, which is basically an artist.”

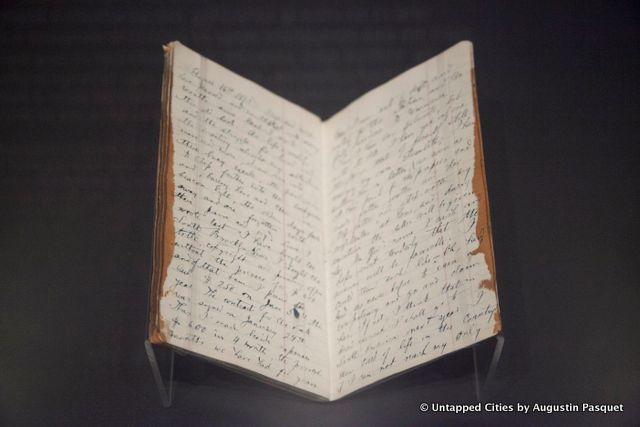

Fortunately for historians and us, Riis kept impeccable care of his notebooks, in contrast to the photographs. The exhibition showcases a few originals. One is a pocket diary from 1875, seen in the first part of the exhibition. Shown is Riis’ final entry, after four years of writing in several journals, covering the early years of his immigration to the United States. Riis was just 21 when he crossed the Atlantic in 1871, hoping to make a life for himself, establishing a career to convince his love, Elisabeth, to marry him. As the exhibition describes, the journals “recount a period of struggle and painful self-doubt.”

In the exhibition, his journal is open to the last few pages, where he expresses hope that Elisabeth will now say yes to his offer in marriage: “In God’s name I wish and hope most tenderly that the answer will be favorable. I would then work like – Oh, hard, hard, as ever before to earn competency and go and claim her. If not, I think that in dead earnest I shall go to South America next year. I am tired of this country if I cannot reach my only aim and object of so many long years.”

Elisabeth did say yes and Riis stayed in New York City for the rest of his life.

Bandit’s Roost. Photo by Jacob A. Riis. Image via Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Roger William Riis

This is possibly our favorite image in the exhibition – a documentation of the lawlessness and self-policing occurring downtown. Bandit’s Roost was an alley off Mulberry Street, near Riis’ office across from police headquarters. Of course, the casual posed nature of the people in the foreground likely suggests some form of complicity between subjects and photographer.

Check out Jacob Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half at the Museum of the City of New York and look for the museum’s special programming around this exhibit and Affordable New York: A Housing Legacy.

Subscribe to our newsletter