After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

Untapped New York has uncovered the secrets of a lot of the major “squares” in New York City, including Times Square, Herald Square, Union Square, and Washington Square Park, among many others. Next up is Madison Square, alongside Madison Square Park. The park, named for James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, has been an urban public place since 1686 but officially became a public park in 1847 when the area was a bustling, trendy shopping district.

On August 11 at 12 p.m., Untapped New York Insiders are invited to join our Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers for a virtual talk, during which he will reveal the secrets of Madison Square Park. Did you know that the park was home to some of the most famous art installations in New York’s history, including the torch of Lady Liberty? Discover the story behind the monument to New York City’s first public Christmas Tree. Uncover a historic tree in the park with a special history rooted in the park’s name. Learn about the park’s role in the invention of baseball. Hear about a hidden mausoleum right next to the park which is one of only two in the whole city. The event is free for Untapped New York Insiders (and get your first month free with code JOINUS). Without further ado, here are our top 10 secrets of Madison Square.

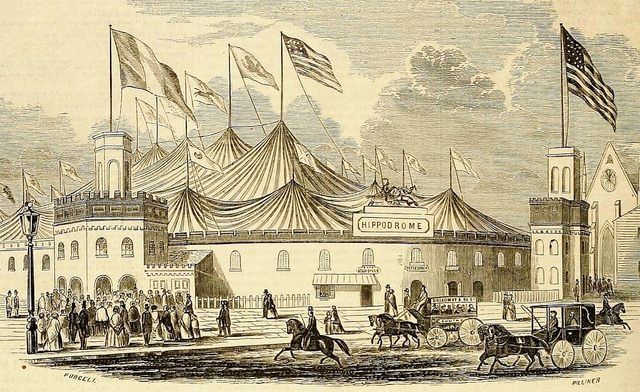

Today, we know that Madison Square Garden is located on the West Side of Manhattan in Pennsylvania Plaza. However, the “World’s Most Famous Arena” had its origins right here in Madison Square. The block northeast of Madison Square Park (between 26th and 27th Streets) was the site of the first and second Madison Square Gardens (there were four versions in total). Madison Square Garden originated in 1873 when P.T. Barnum started hosting his circus in an obsolete railroad depot north of Madison Square, owned by Commodore Vanderbilt. He made it the site of his “Great Roman Hippodrome” every year, and the first arena officially became a reality in 1879. In fact, the circus kept the first (and financially poor) Madison Square Garden building stable.

However, structurally speaking, the building could not stay up, and it was demolished in 1889. To avoid missing more than one show season, a second Madison Square Garden Building was built at the same location, designed by famed architect Stanford White. Workers built it around the clock so that just a year later, in 1890, the building was completed (and was the second tallest building in the city) until it was closed in 1925. The second Madison Square Garden was no stranger to notoriety, though. White actually built himself a seduction lair inside the building and was later shot to death on the roof. White’s apartment was inside the Madison Square Garden tower, making it an easy target for his murderer, Henry Thaw, who was jealous because of a love triangle. The third version of Madison Square opened in 1925 but at 49th street and 8th Avenue.

Every year, people around the country await the Christmas tree lighting at Rockefeller Center to ring in the holiday season. Though it’s now a nationally popular tradition, American Christmas tree displays actually find their origins in Madison Square Park. The first, albeit simple, public Christmas tree lighting occurred here in 1912. The Madison Square Park tree was called the “Tree of Light,” and it was also mentioned as the hallmark of a “community Christmas” at the national tree lighting at the East Plaza of the US Capitol. The Adirondack Club donated a tree 60 feet tall and 20 feet wide, and the cost of transport was covered by an anonymous railroad worker. Over 20,000 New Yorkers of all social classes attended the tree lighting ceremony.

Interestingly, the tree was erected for more than just the holidays; it was part of a progressive movement to address New York City’s socioeconomic inequalities. According to The Bowery Boys, Emilie D. Lee Herreshoff planned the tree lighting to emulate European civic customs as a “clean, proper, somber affair, closely tied to Jacob Riis’s equally non-riotous New Year’s Eve celebration scheduled the week after — righteous counter-programming to the Times Square celebration.” Riis believed that the holidays weren’t a time for wild behavior, and that events like Christmas tree lightings would give the poor “acceptable” alternatives. Today, the Star of Hope monument in the park honors the approximate location of the first tree lighting.

Many are familiar with Washington Square Park’s iconic arch, but did you know that Madison Square once had some iconic arches of its own? In 1889, for the centennial of George Washington’s first inauguration, two temporary arches were built over Fifth Avenue and 23rd and 26th Streets. In 1899, the Dewey Arch was built over Fifth Avenue and 24th Street in Madison Square for a parade honoring Admiral George Dewey and his victory in the Battle of Manila Bay. It remained until 1901.

Though there were attempts to rebuild the arch in stone, plans weren’t executed and the arch was demolished. In 1918, Mayor John F. Hylan had a “Victory Arch,” created at this same location to commemorate people from New York City who died in the war. There were failed plans to make it permanent, and some felt it was too vengeful against the Germans.

There is another aspect of Madison Square Park that pedestrians probably don’t notice every day: the James Madison Tree between 24th and 25th Street. This Red Oak was actually excavated from Madison’s Virginia estate. It was planted in the park and dedicated to James Madison by the Fifth Avenue Association in 1936 to celebrate Madison Avenue’s centennial anniversary.

Red Oaks can live for up to 500 years, so the nearly 90-year-old James Madison Tree is still relatively young. New Yorkers have made efforts to maintain the beauty of the tree and preserve it for generations of New Yorkers to come. Trees in the park receive special protection due to the Madison Square Park Tree Conservation Plan which catalogs the trees currently within the park, while choosing the future trees to be planted there.

Madison Square Park, perhaps unsurprisingly, used to be a cemetery (Herald Square, Union Square, and others in New York City were once cemeteries as well). It was also a potter’s field (a burial ground for those who died unknown or couldn’t pay for a burial in other cemeteries), between 1794-1797, but the field moved to Washington Square Park.

After its time as a potter’s field, the land became the site of a U.S. Army Arsenal and then a military parade ground that was named “Madison Square” in 1814. Both made for a key military post for drills during the War of 1812. Once the arsenal lost its military usefulness in 1825, it became a “House of Refuge” for juvenile delinquents until 1839 when a fire destroyed it. The land between 23rd and 26th Streets from Fifth Avenue to Madison Avenue officially became a public park with a fence in 1847.

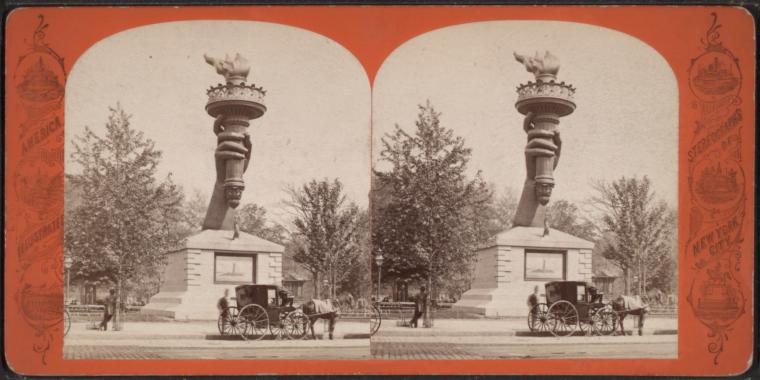

Though it’s now a national symbol and popular tourist destination, the Statue of Liberty had a difficult road to construction. Designed by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and Gustav Eiffel, the Statue of Liberty arrived in pieces from France. Starting in 1876 until 1882, the Statue of Liberty’s arm and torch were displayed in Madison Square Park to raise money for the construction of the statue and its base.

For a short while, it seemed as though the arm was all that America could get its hands on. Along with New York, Philadelphia and Boston fought over access to the arm. Though on October 28, 1886, the full Statue of Liberty was installed and dedicated on Liberty Island.

Many debate the origins of baseball, some claiming the sport began in Cooperstown, others Hoboken. But some attribute the beginnings of the sport to Madison Square Park in 1845. A 25-year-old law clerk named Alexander Cartwright formed the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, drawing from other sports for the rules. Some of these rules still are in effect, including a nine-inning game and pitching mechanics.

Cartwright and his teammates would practice baseball in Madison Square Park at Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street before moving to the Murray Hill Grounds at 34th Street and Park Avenue. By the time of the move, these rules were spread nationwide, thus many make the claim that the Flatiron District was the true birthplace of the American pastime.

In Madison Square North, there is an obelisk that was established in 1857 over the tomb of General William Jenkins Worth. The obelisk is one of two monuments in New York City that is also a mausoleum, the other being Grant’s Tomb in Morningside Heights. James G. Batterson designed the granite obelisk, whose inscription outlines his military achievements.

Worth served in the Seminole Wars and the Mexican-American War, also inspiring the name Worth Street in Manhattan. He succumbed to cholera in 1849. The city designated the area around the obelisk as a mini-park called “General Worth Square.”

New York City has been the site of many serious protests that have incited large-scale change, but in 1901, a protest over something frivolous occurred in Madison Square Park. At this time, an English businessman named Oscar Spate convinced the Parks Commissioner to let him pay the city $500 annually to place 200 cushioned rocking chairs in Madison Square Park, Union Square, and Central Park, and then charge New Yorkers five cents to use them. He got the idea from London and Paris, whose parks sometimes followed this practice of charging pedestrians for seating, and he also wanted to discourage homeless residency in the park. Spate’s rocking chairs even replaced free benches in shady locations.

When a July heat wave occurred, the pedestrians of Madison Square Park refused to pay to sit in the shade and even deliberately went there to sit in the rocking chairs without paying. The police got involved when 1,000 men and boys chased the chairs’ attendant from the park and broke the rocking chairs. The great “Rocking Chair Riots of 1901 lasted several days, and that same month, the Parks Commissioner canceled the five-year contract with Spate. A 10,000-person celebration with fireworks ensued. A determined Spate took the Parks Commissioner to court for ending the contract, but the judge didn’t force the public to pay for seating. In fact, the Evening Journal then asked for an injunction against such paid chairs, causing Spate to finally relinquish his cause. Spate also sold the chairs to Wanamaker’s Department Store, where they were advertised as “Historic Chairs.”

The Museum of the City of New York published an interesting piece on the evolution of Madison Cottage, which is in today’s Madison Square Park. By the 1840s, a popular roadhouse called “Madison Cottage” occupied the land that would eventually be the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street. The cottage had many functions: a post-tavern, stagecoach stop, cattle exhibition hall, and gathering place for lovers of horse racing.

In 1853, however, it was razed to pave the way for a Roman arena called “Franconi’s Hippodrome,” which featured chariot races, wild animal acts, and other circus-like performances. However, the hippodrome was extremely unsuccessful. In 1856, a huge change occurred: the circus arena was demolished and replaced by the luxurious Fifth Avenue Hotel, which had the first passenger elevators ever and whose guests were considered among the most socially elite in New York City. About fifty years later, the hotel was razed and became the home of the International Toy Center, which is now home to Eataly.

Next, read the Top 10 Secrets of Times Square NYC, The Top 15 Secrets of NYC’s Union Square, The 10 Ten Secrets of NYC’s Herald Square, and The Top 10 Secrets of Washington Square Park.

Subscribe to our newsletter