The Stolen Queen: A Mystery Whodunnit Set in the Met Museum

Author Fiona Davis shares the inspiration for her latest historical fiction novel set in NYC!

Like many places in Chinatown, 50 Bowery is a site with layers and layers of history – since the days of the early settlement, it played host to waves of immigration and entertainment, and today is undergoing conversion into its latest incarnation: a 22-story hotel being developed by one of Chinatown’s notable real estate families. Starting in December, we were given special access to the construction site at 50 Bowery, along with the numerous archeological finds discovered beneath the site. While the New York Times has also recently covered the history and controversy amidst this historically rich site, we will show here the many unique remnants found during the excavation for the hotel.

For the historical documentation, 50 Bowery Holdings, LLC hired Chrysalis Archeological Consultants, the renown firm that has lent its expertise to the burial finds beneath Washington Square Park and other notable sites in New York City. As 50 Bowery was not landmarked and is not within a historic district, the Chu family did not have any legal obligation to perform an archeological study – but Jonathan Chu and his sister Lauren become fascinated by the site’s history and agreed to fund an assessment. The Chu siblings have also been avidly collecting ephemera from the site’s history, sometimes accidentally bidding against each other on eBay. As Jonathan shows us, some of what they’ve been able to purchase online has been of far better quality than those he ave found in museums, and the items form a nice counterpart to the actual artifacts uncovered in the archeological dig.

Items purchased by the Chu siblings about 50 Bowery and its surrounding sites, including the Chinese Tuxedo

Walking through the finds with Alyssa Loorya, President and Principal Investigator of Chrysalis Archeological Consultants, she informed us that the team even “brewed recipes based on this project – we made bitters, we made a beer, and an elixir of long life.” The site at 50 Bowery was at varying points a tavern (possibly the Bull’s Head Tavern which was either partially at or around the property), the Atlantic Garden (a famous German beer garden), a theater, a hotel and a stove dealership. In more recent years, it has been a Chinese restaurant, a Popeyes, and a Duane Reade.

Jonathan Chu at the construction site in December

Loorya contends that there’s a “great level of continuity of this one plot of land as a stopping point for travelers in and around the city, and will be again.” The items discovered also tell the story of changing immigrant communities. 50 Bowery was on the edge of what was Kleindeutschland, settled after by the Italians and the Chinese. As such, the finds include bottles, dishes, pots, tiles, and more, brought together through the continuity of culture and uses at this site. Whereas the previous structures at 50 Bowery have come and gone, the history lives on in the myriad of items found here.

Here are 15 items in the study we found the most fascinating:

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

One of the recipes the Chrysalis team made was an “elixir of long life,” inspired by this small glass vial found on the site. Emblazoned on the bottle are the words “Die Keisserliche Privilegirt Attonatiche W. Kronessents” which translates to “The Royal (Kaiser) Privileged Altona Essence.” According to the Chrysalis report, “this was a medicinal tincture produced under the auspices of the crown near Hamburg, Germany.”

Loorya places this bottle within the context of Prohibition, when medicinal beverages became an easier way to procure a drink during this time. “We were able to find a patent recipe for it, and it was one of the things that we brewed,” Loorya says. Unfortunately, she continues, “It tasted absolutely horrible.” Loorya describes that the tonic was meant to only be tasted a few drops at at time, placed on the tongue.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

Bitters go back to ancient Egypt, says Loorya, and they tend to have similar ingredients compared to those used today. Though they come in slender bottles now, they used to come in larger bottles like this one by Dr. Jacob Hostetter, based in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who produced a best-selling bitter that was a whopping 94 proof. Though it was intended as protection against various maladies that a pioneer explorer or Civil War soldier might catch, Dr. J. Hostetter’s bitters were not surprisingly also served as an actual drink ordered by the glass.

The team at Chrysalis made the bitters, infused over a two-week period, based on a recipe they found, and sought out all the natural ingredients, including Peruvian bark from local apothecaries and distributors online. Nonetheless, Loorya says, “I’m certainly not drinking it by the glass…but we gave out little bottles to people, and I’ve had friends who have used it in mixed drinks and they said it’s made the best Manhattans they’ve ever had.”

A portion of a poem from Hostetter’s United States Almanac from 1867, part of a million dollar advertising campaign by the company states:

For these, though Mineral nostrums fail,

Means of relief at last we hail,

HOSTETTER’S BITTERS medicine sure,

Not to prevent, alone, but cure.

Lauren Chu placed one of Hostetter’s bottles inside a new time capsule in the foundation of 50 Bowery. An 1826 time capsule was sealed on the site during the construction of the theater but was never found. “Clearly someone got to it before us,” says Loorya.

In addition to discarded bottles and plates, Chrysalis uncovered parts of the Atlantic Garden itself. In the excavation, part of the wall and part of the floor of Atlantic Garden were uncovered with artifacts found in the dirt within. Loorya believes these tiles, created by the American Encaustic Tile Company, were extras because no mortar was found on them. They nonetheless show how colorful and decorated the building would have been. You can also find tiles by the prolific tile company in the Columbus Circle subway station.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

The Atlantic Garden was so successful that they ended up expanding onto the plot of land next door to 50 Bowery to 52 Bowery, and all the way to the Elizabeth Street side. Eventually, the basement of the Atlantic Garden, which once had a bowling alley was filled up and built on top of.

In addition to these founds below ground, the Chu family removed a pulley from the vaulted retractable roof of the Atlantic Garden, bricks and wooden beams from the structure before demolition began.

It should be noted that no artifacts or archeological structures were discovered from the 18th century, when the site could have been the Bull’s Head Tavern. The Crysalis report notes, “It is possible, however, that the fieldstone portions of the wall uncovered at 50 Bowery were remnants of the Bull’s Head Tavern, incorporated into a nineteenth-century construction, either the 1825-1827 Theatre Hotel or the later structure of the Atlantic Garden,” but the team found it more likely that those portions were more likely constructed at the same time.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

“New Yorkers have always been drinking bottled water,” Loorya jokes, but with valid supporting evidence. In addition to a 1790 bottle her team found at South Street Seaport, this stoneware bottle from Kronthal Springs in Kronberg, Germany was found at 50 Bowery. Some of the springs in Germany were known for their medicinal properties and were imported into the United States. Mineral water from Kronthal Springs were

first bottled in 1875. In 1899, 4000 cases of Kronthal mineral water were shipped to the United States.

The Star of David was used as a medieval brewer’s symbol, known as the “Brewer’s Star,” which was used in the above bottle by the Brooklyn-based North American Brewing Company, and by other beer companies. According to this report, “the brewer’s star was intended to symbolize purity; that is, a brewer who affixed the insignia to his product was thereby declaring his brew be completely pure of additives, adjuncts, etc. In fact, folklore has it that the six points of the star represented the six aspects of brewing most critical to purity: the water, the hops, the grain, the malt, the yeast, and the brewer. But others assert that the emblem’s use by beer-makers originated independently of the Jewish Star, and has no historical connection thereto…It is known that the star was the official insignia of the Brewer’s Guild as early as the 1500s, and that its association with beer and brewing can be traced as far back as the late 1300s.”

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

It took a while for Chrysalis to figure out what these were – copper pressure cooker lids used to cook traditional German fare. Loorya believes these can be restored to look closer like their original shine. In addition to cooking ware, animal bones including a bone from a cow were were discovered at the site and determined to be food remains. “Many had cut marks showing butchering or marks from utensils used by the diner,” the Chrysalis report states.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

This light blue bottle is notable because it was discovered with the paper label still partially intact, with an address on the Bowery.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

Dozens of the light teal Zoolak bottles, containing a lightly fermented milk drink, were found at the site. It was created by a Dr. Dadirrian (whose name is on the bottle) and produced by Edgar E. Wright of Brooklyn. The recipe, for every 100 parts Zoolak included:

Water 87.69

Proteid substances 3.98

Fat 4.91

Milk-sugar 2.03

Alcohol 0.07

Ash or mineral salts 0.78

Lactic acid 0.50

Carbon dioxide 0.04

Loorya says Zoolak would probably be similar to kafir, based on what she has researched about it, but the team has yet to recreate a sample to date.

You can catch advertisements for Zoolak on New York City billboards in vintage photographs.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

This tiny milk creamer jug, known as the Mildred, comes from England and was imported by L. Straus & Sons, opened by Lazarus Straus, the fater of Isidor Straus who purchased Macy’s (and perished on the Titanic with his wife Ida).

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

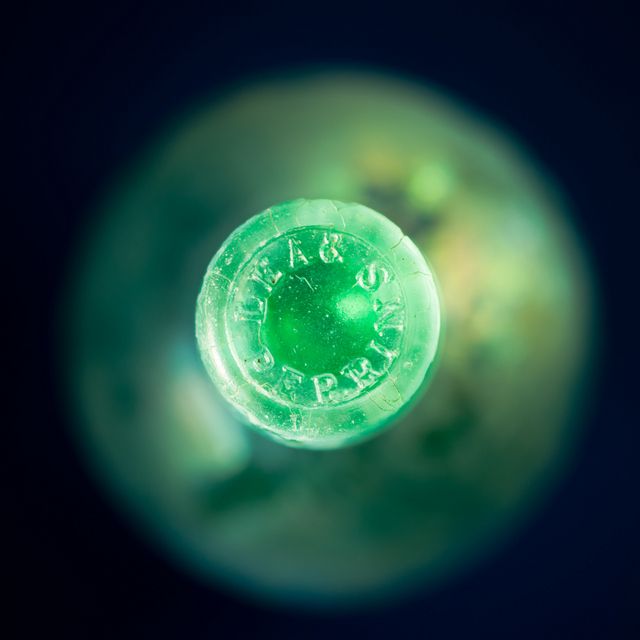

Starting in 1838, Lea & Perrins’ Worcestershire Sauce was sold out of a chemist shop in Worcester, England run by John Wheeley Lea and William Henry Perrin. This bottle made its way to 50 Bowery and was found intact with the glass stopper, a style of bottle not in use until 1850.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

E. and J. Burke, consisting of the brothers Edward Frederick Burke and John Burke, were Irish brewers, bottlers, distillers and importers who had locations in both Manhattan and Long Island City. For a period of time, they were the exclusive bottlers for stout brewed by Arthur Guinness, Son & Co.

Products produced under their own label had a cat as their mascot, seen at the bottom of the bottles (shown above). In 1943, Guinness bought the Burke brewery, the second brewery the company operated outside of Ireland and its first in the Americas.

The above is one of the large oyster shells collected on the site. The size of a hand, it was of typical size for a pre-20th century oyster, according to Chrysalis. Oysters were consumed at a rapacious pace by both the city’s rich and the poor. By the early 1900s, over 1 billion oysters were harvested per year from New York harbor. Read more about the tragic history of New York City’s oysters and the multi-pronged efforts for their revival.

Photos by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

The Bürgerspital Vineyard in Germany is one of the oldest vineyards in Europe still in production, first planted in the year 1334. The flat, round bottles from Bürgerspital, known as Bocksbeutel, were based on the shape of a leather sack pouch and are quite similar in shape today. In fact, according to the Bürgerspital website “In 1726 the Council of the City of Würzburg decided that the ‘Bocksbeutel’ be the mark of quality compared with poorly produced wines. At the ‘Council’s behest, the first sealed specimens of the Bocksbeutel are stored in Bürgerspital’s cellars and the true, the pure, unadulterated wine, rapidly and brilliantly triumphed’, reported the District Archivist Sebastian Göbl.” Loorya reports that there are currently attempts to import this wine to the United States.

Photo by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

Many of these thick, ceramic utilitarian plates were found on the site at 50 Bowery, including several stamped “HOTEL,” dumped into the alcoves of the Atlantic Garden. The archeological analysis suggests that portions of the Atlantic Garden may have been repurposed from the structure of the Theatre Hotel that came before it.

Other plates found at the site were more detailed, including this plate that tells the Chinese “Willow” folklore story, a popular design used on porcelain plate ware from England starting in the late 18th century.

Photos by Chrysalis Archeological Consultants

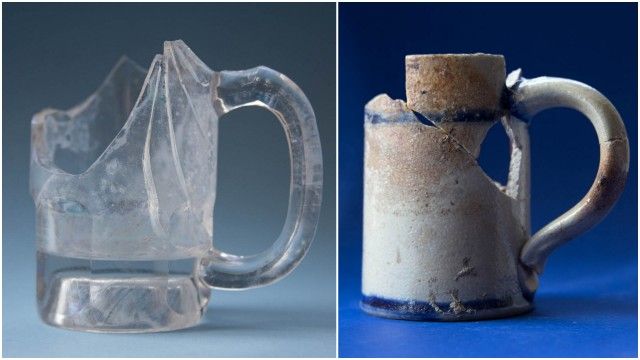

Various beer steins were found, which is logical given the historical usage of the property. One thing to note says Loorya is that the intact nature of most of the finds, or the ability to put pieces back together easily, demonstrates that these archeological finds are primary deposits.

One beer bottle, labeled CC Haley & Company’s Celebrated California Pop Beer, comes from sometime between 1872 and 1885. The Chrysalis team attempted to make a small batch of the California Pop Beer, and Loorya says “it was really tasty. A minty berry, lemonade-y thing, flavored with spruce and wintergreen.” The beer also contained spruce oils, sassafras and ginger root.

Intact, hand blown bottles. None of the bottles found at 50 Bowery were machine produced, but were blown into a mold, which dates the items to the 19th century.

Intact, hand blown bottles. None of the bottles found at 50 Bowery were machine produced, but were blown into a mold, which dates the items to the 19th century.

Lauren Chu tells us that the family is still working out where the archeological finds will be showcased, but they will be somewhere within the hotel. In addition, the hotel will house an outpost of the Museum of Chinese America.

Next, discover 5 Alleys and Small Streets in Chinatown and take a peek into the construction at 5-7 Doyers Street, where gangs once used underground tunnels to escape.

Subscribe to our newsletter