✨You Can Touch the Times Square New Year's Eve Ball!

Find out how you can take home a piece of the old New Year's Eve ball!

Bloomingdale’s is one of those storied New York City department stores that grew from a small shop to the megastore it is today. While the gleaming store may not seem to hold many secrets, we’ve uncovered some truly fun ones – after all, it’s hard not to accumulate some great history if you’ve been around since 1860.

Lyman Bloomingdale first opened the store, Ladies’ Notions Shop, on the Lower East Side with his father selling hoop skirts, a style popularized by Empress Eugénie of France. In 1872, Lyman’s brother Joseph, returned to New York after working as a traveling salesman. The two brothers opened “Bloomingdale’s Great East Side Bazaar” on 3rd Avenue between 56th and 57th Street, a bet for the time period, because the shopping district was still located downtown. To counter this, the East Side Bazaar sold far beyond hoop skirts. Differentiating from other retailers at the time, who generally specialized in one type of garment, the Bazaar carried a variety of women’s and men’s fashions, most which were imported from Europe. It was the precursor of the modern-day department store.

Neighborhood demographics began to shift, as the city’s wealthy moved further and further uptown to construct their Gilded Age mansions. The construction of the Third Avenue elevated rail further supported the prospects of the uptown store, and a 1902 advertising campaign surrounded the theme “All Cars Transfer to Bloomingdale’s.”

Laid in the cornerstone of the Lexington Avenue flagship of Bloomingdale’s in 1930 are two time capsules that allegedly contain an autographed baseball from Babe Ruth and a number of other historical paraphernalia. The time capsule is supposed to be opened in 2130. Of particular interest is the presence of three banks books with deposits of $25 each, intended to collect compound interest over 200 years, which could be worth millions today. Read more about the time capsule here.

In 1886, the store moved to 3rd Avenue between 59th and 60th Street, but growing demand necessitated more expansion and the rest of the block was bought over the next 15 years. But despite renovation into an Art Deco style in the 1930s, two French Empire style portions still remain between the two larger portions of the block.

The vintage photograph below provides a glimpse of what 60th Street looked like. It seems that this side has always been utilized as a loading dock (albeit with horse and carriage back then). There are two French Empire style buildings about halfway down the block. The rest of the block, moving towards Lexington Avenue, was demolished to make way for the Art Deco-style department store we know today.

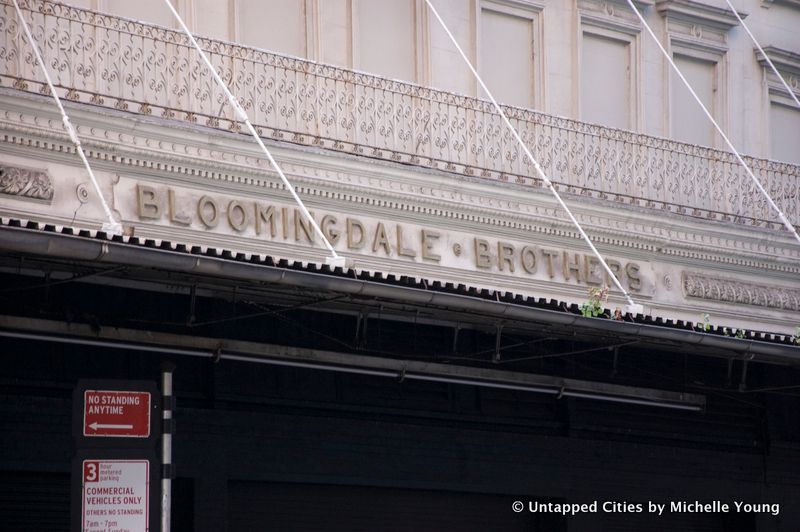

The words “BLOOMINGDALE BROTHERS” is also still visible on this facade:

The first marathon to take place in the NYC area happened in November 1907 and was won by a Bloomingdale’s employee named John J. Hayes, also known as “Johnny.” Hayes was then the assistant to the manager of the sporting goods department.

The 25 mile “marathon” took place in Yonkers, with Hayes training on the roof of the Bloomingdale’s store, on a cinder track made for him by the company. One year later, in London, Hayes, born to Irish immigrants, would go on to win the Olympic Gold Medal and set the world record. He was the first and only Olympic gold medalist to enter into the marathon until 1972, and was promoted to manager at Bloomingdale’s following his Olympic win.

Though now closed, this quirky gem of a restaurant had been located inside Bloomingdale’s since 1979. Le Train Bleu was modeled after a dining car of the French luxury train, The Calais-Mediterranée Express which was an overnight train between Calais, in the north of France, and the French Riviera that ran from 1886 to 2007. The hallway to the “dining car” had the feel of a real train (and some vintage travel posters to boot), and the car itself was decorated with mahogany, plush green detailing and Victorian-style lamps.

As Scouting NY reports, “Le Train Bleu restaurant was the brainchild of Marvin S. Traub, who fought in World War II, received a master’s in Business from Harvard, and worked his way up from the bargain basement of Bloomingdales to become president in 1969. In his NY Times obituary, he is credited with transforming Bloomingdale’s ‘from a stodgy Upper East Side family department store into a trendsetting international showcase of style and showmanship.'”

In 1984, Bloomingdale’s sold 35 ounce bags of ice chips from a 100,000 year old glacier in Greenland for $7 a bag, branded as “Glazonice.” At the time, the store marketed the ice as the oldest and purest you can find on the planet. It was also said that because of the denseness, it would not dilute your cocktail. The ice, all 4000 pounds of it, was purchased through the company of a polar explorer, William Baker, who was also had of W Communications television group. As Baker told The New York Times, ”What’s more perfect for celebrating the birth of a child or a wedding than 12-year-old Scotch with 100,000-year-old ice?” The Sun Journal reported in 1984 that more than 60 bags were sold in the first two weeks and that people were driving into the city from places like New Haven to pick it up. On the silver mylar bags was also the claim: ”Put your ear close to the glass and listen to the whispering of the past.”

Master designer and Helvetica font proponent Massimo Vignelli, who also created the graphic standards for the New York City subway, designed the Bloomingdales logo, a variation on the Bauhaus font, Futura. As New York Magazine reports, “Rumor has it that the solution was completed minutes after the client had walked out the door; Massimo waited several weeks to reveal it in order to justify his fee. Whatever it was, Bloomingdale’s got its money’s worth.”

Vignelli also designed Bloomingdale’s iconic “Brown Bags,” that initially came in little, medium and big sizes, and its boxes. There have since been expansions into “Tiny Brown Bag,” for gift bags, “Tiny Brown Card,” along with bags with the same design in a patent-leather style.

Bloomingdale’s rents its skybridge from the city of New York and must pay rent annually. They are not allowed to demolish the structure but must upkeep and renovate it according to its physical needs. This skybridge connects Bloomingdale’s shopping center to its business offices across the street. This skybridge is accesible to the public through the Bloomingdales entrance on the third floor.

window.gie=window.gie||function(c){(gie.q=gie.q||[]).push(c)};gie(function(){gie.widgets.load({id:’eENZiBASR8JkUvYccT4uiQ’,sig:’LCx8EedfVwcOfyBsNnqqXWdz54Wfgu7-61ZD9sqP2Bk=’,w:’390px’,h:’594px’,items:’583901355′,caption: true ,tld:’com’,is360: false })});

In 1976, on her second visit to New York City, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip spent an afternoon in Bloomingdale’s – likely a public relations stunt agreed to on both the department store side and the royalty side. The New York Times reported that “the Queen seemed slightly bewildered.” The same Marvin Traub, who dreamt up the Le Train Bleu restaurant told The New York Post that Queen Elizabeth “didn’t choose Saks, and she didn’t choose Bergdorf — she chose Bloomingdale’s.” Another Bloomingdale’s employee told the New York Times, “we thought — and the Queen agreed — that it would be a very American experience for her to go amidst all the crowds and just pretend she might be shopping.”

Regardless, the Queen’s arrival to Bloomingdale’s meant a reversing of traffic on Lexington Avenue so that she could get out of her car on the right side. As The Bowery Boys describe, she then went “quietly” from floor to floor looking at the goods, admiring the British imports, was shown a fashion show, and met designers like Calvin Klein. The Prince meanwhile was shown Bloomingdale’s best sellers which included at that time a “Talking Calculator” and a pet rock.

Bloomingdale’s “Model Rooms” came into being in 1947, but received worldwide acclaim starting in the 1970s with its over the top installations and star-power curators that included Frank Gehry and filmmaker Federico Fellini. One room, entitled “The Cave,” was sprayed completely in white polyurethane. According to The New York Times, the Model Rooms on the fifth floor “became a mecca in the 1950s for those who aspired to learn what was stylish, sophisticated, well-made but not too expensive in a living room set or a window treatment.” The most famous of the decorators was Barbara D’Arcy, author of the book Book of Home Decorating which featured photographs of the rooms in the 1960s and 1970s.

On Queen Elizabeth’s visit, she walked through model rooms that had American reproductions of English antiques, and she stared at the Chippendale chairs and remarked “What wide chairs!”

Next, check out the top 10 secrets of the Plaza Hotel.

Subscribe to our newsletter