Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

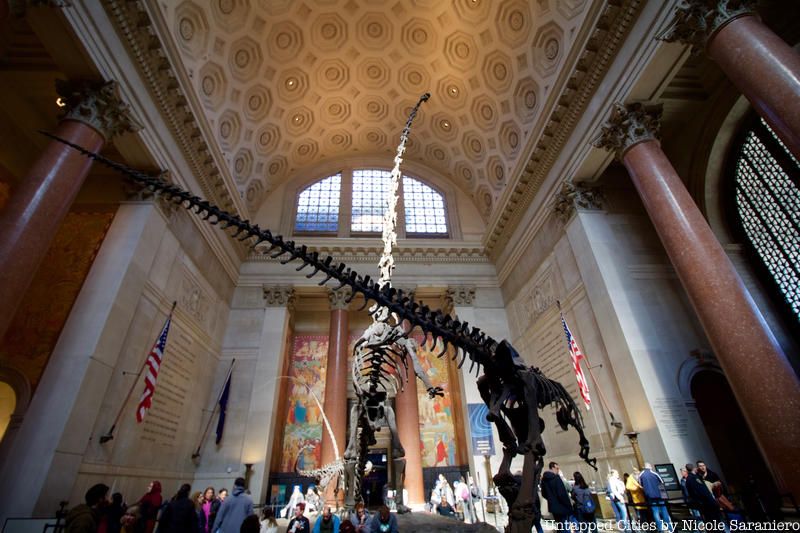

With its trademark dioramas and extensive collections, the American Museum of Natural History on the Upper West Side, is one of the most prominent museums and scientific research centers in the world. It encompasses four city blocks and consists of more than 27 interconnected buildings with over 45 permanent exhibit halls. Its physical vastness aside, it also has over 200 working scientists and sponsors over 100 annual field exhibitions. Thus, it was, and still is, a pioneer in discovering and circulating information on human culture, the natural sciences, and the universe. With all of this impressiveness, it’s not surprising that the museum and its history are packed with equally impressive secrets. Here are our top twelve.

In 1871, after much pleading, fundraising and petitioning, the first of the museum’s exhibits went on display at its original location in the Central Park Arsenal building. The museum was conceived by Albert S. Bickmore and backed by prestigious men like J.P. Morgan, Andrew Haswell Green and even Theodore Roosevelt. By 1876, the museum had over a million visitors each year, which was almost 10% of all Central Park visitors.

By 1877 it became clear that the flourishing museum needed more space, so it moved to Manhattan Square-a chunk of land across the street from Central Park between West 77th and 81st streets.

The American Museum of Natural History has a huge digital gallery with vintage photos of the museum, which you can scroll through here.

Architects Calvert Vaux (who helped design Central Park), and J. Wrey Mould had grand plans to occupy the entire Manhattan Square space. These plans included a domed, five-story square around a Greek cross with four courts and an octagon shaped crossing. Vaux also planned for the museum’s edifice to be 700 feet long on each side, centered around a massive tower called the “Hall of the Heavens.”

In fact, according to New York 1880, Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, the American Museum of Natural History would have been the world’s largest museum and the largest building in North America at the time, if these plans hadn’t been altered.

The new museum didn’t get off to a great start-by 1886 attendance was one-sixth of what it was at the Arsenal. You’ll learn more about this rocky start next.

During its early days at both the old and new locations, the museum ran into financial troubles, mostly because it bought expensive collections; in 1874 it purchased a fossil invertebrate collection for $65,000. According to Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion into the American Museum of Natural History by Douglas Preston (who worked for the museum), the museum hoped to pay for it with a public subscription fee. Unfortunately, the public wasn’t interested in the collection, leading to serious debt.

In 1880, with the trustees cracking down on spending and visitors at a low, its president even suggested closing it. But thanks to Morris K. Jesup, one of the founders, the museum still stands today.

Jesup, who then became the museum’s third president, completely transformed the museum to save it. Under his leadership, which lasted over 25 years, he increased the size of the exhibition space from 54,000 square feet to 600,000, increased the number of workers from 12 to 185, and landed an endowment that was over a million dollars. Most importantly, he pioneered the Museum’s practice of sending people on expeditions, propelling it into an era of exploration.

Considering that as of 2014, it has received nearly $50 million from visitor donations and admission fees, it’s hard to imagine the museum’s former emptiness.

Preston also recounted the fascinating early history of the museum in his book. According to him, there was almost a Paleozoic Museum based on London’s Crystal Palace (which was in Sydenham Park) in Central Park instead. A British artist named Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins had grand plans to restore and decorate Syndenham Park with pools, fake geographic structures and life-sized dinosaur models.

This park “caused quite a sensation,” so that news of its restoration quickly reached the U.S. In 1868, the head of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park, Andrew Green, decided to build a similar Paleozoic Museum in Central Park, which was still undergoing construction. He personally wrote to Hawkins asking him to undertake this task.

Hawkins came and collected fossils from around the U.S. (the museum was only dedicated to American creatures). There would have been a “giant iron framework covered with vines” arching the museum, and there was going to be “a menagerie of extinct mammals and dinosaurs.”

What happened to these extravagant plans? Boss Tweed hired henchmen from the Tweed Ring to break into Hawkins’ studio and sledgehammer his molds and dinosaur models to pieces. (Nope, not kidding).

Since Tweed couldn’t profit from such an establishment, he initially disguised henchmen as Central Park commissioners, who ordered that the museum’s foundations be plowed. However, a determined Hawkins kept working on his project, so Tweed took direct action to get his way. One of the henchmen even told Hawkins that he “should not bother himself about dead animals when there were so many living ones to care for.”

Boss Tweed, who then tightly controlled the state legislature as senator, was actually one of the people who happily approved the construction of Bickmore’s American Museum of Natural History. Bickmore himself approached the intimidating politician with a letter from a former New York governor and friend of Tweed’s requesting the bill’s approval.

Tweed was evidentally less sympathetic towards the devastated Hawkins, who soon returned to England.

After the museum moved to Manhattan Square, it was President Ulysses S. Grant who laid the first cornerstone at its permanent location 1874, three years before it opened. As documented in a New York Times article from the May 30, 1874 issue, a number of distinguished guests watched this happen and there was even a prayer and live music.

Though the American Museum of Natural History currently has one of the largest history collections in the Western Hemisphere, it only had a single volume for quite a few years after the founding of the original museum.

According to Sci-tech Libraries in Museums and Aquariums, there was no official library at the museum’s initial home in the Arsenal Building. Bickmore himself donated the museum’s first official volume, Travels in the East Indian Archipelago, which marked the beginning of its library collection and is now in the museum’s Rare Book Section. Eventually, Bickmore handed over his whole collection and worked towards soliciting more donations (rather than purchasing books). Only when the museum moved to Manhattan Square was a formal library established in an attic.

Over the years, the library accumulated impressive amounts of works, partially due to its merging with the Department of Maps and Charts and the addition of the Photographic Collection. By 1916, it encompassed five rooms. In 1961, it moved to its current location, and now has over 550,000 volumes.

Many know Theodore Roosevelt as a naturalist and fervent lover of the great outdoors. He would often go on hunting trips and return with game. One of his largest donated game was a cow elephant he shot on a 1909 hunting trip with his son Kermit, who shot the elephant’s calf. This elephant is in a display consisting of eight others in the middle of the Akeley Hall of African Mammals. The hall is named after naturalist and taxidermist Carl Akeley, who was also on the trip with Roosevelt. Roosevelt donated more game to the American Museum of Natural History, though most of it just isn’t on display.

The Sanford Hall of North American Birds is currently home to over 20 dioramas of bird species. Its construction actually played a big role in furthering the conservationist cause and even helped lead to a major refuge and treaty.

At the time of the hall’s construction, plume-hunting for the hat making industry forced many coastal bird species, such as the great egret, to near extinction. Frank Chapman made dioramas to allow visitors to see the magnificent bird species in decline because of the hat industry.

The awareness sparked by these dioramas, along with Chapman’s actions outside of the Museum of Natural History, helped lead to the establishment of refuges like the Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, a federal law that helped protect migratory birds.

Since the museum is filled with such rare and priceless objects and specimens, it’s not too surprising that a major heist took place here. On October 29, 1964, Jack Roland Murphy and Allan Dale Kuhn jumped a fence, climbed a fire escape, crawled along a ledge and swung down to the fourth floor with a rope. Beforehand, to plan such an elaborate entrance, they spent a week visiting the museum to familiarize themselves with its layout.

They then took $410,000 worth of jewels (worth $3 million today), including one of the world’s largest sapphires. However, the burglars were soon caught. Three important jewels, the Midnight Star and De Long Star Ruby, and the Star of India were found in Miami. However, another priceless jewel, the Eagle Diamond, was never found.

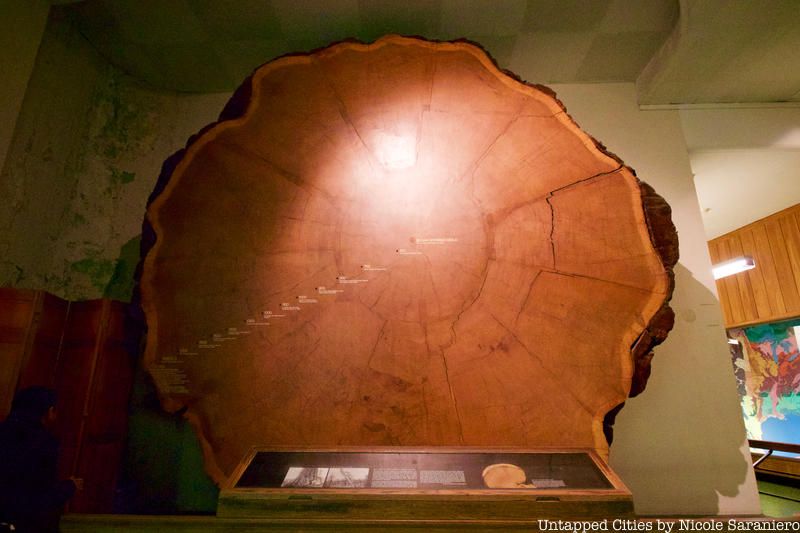

In the Hall of North American Forests in the American Museum of Natural History rests a slice of a 1,400 year old giant sequoia tree. The tree used to stand at more than 300 feet in California, but lumberjacks felled it in 1891. Sequoias have many unique features, including thick, fire-resistant barks, natural wood preservatives and high disease resistance. It is currently illegal to cut one down.

If you were to look up in the Hall of Ocean Life, you’d see a 94-foot-long blue whale suspended from the ceiling, which has been there since 1969. That figure used to be an inaccurate representation of a blue whale, since researchers only based their measurements off a dead whale that was washed ashore in 1925 on Georgia Island.

Once researchers could study a living version of the whale, they found that their previous measurements were off. After the museum was renovated in the early 2000s, the Hall of Ocean Life reopened in 2003. It now had a more anatomically accurate whale with shaved down eye sockets, a trimmed tail, a lip around its blowhole, a naval, and gallons of new paint.

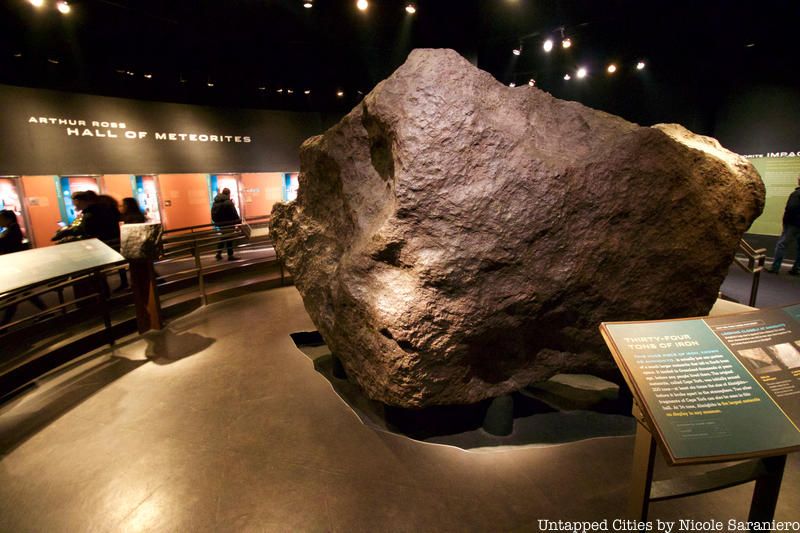

The largest meteorite in the Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites is 34 tons…and supported by columns that reach through the floor and into the bedrock underneath the museum. The meteorite, called “Ahnighito,” is the largest on display in the world and came from a meteorite called Cape York that was about 200 tons and broke apart in the air about 10,000 years ago. It was discovered in Greenland in 1894.

A stainless steel time capsule (called the Times Capsule) occupies a pedestal outside the museum’s Columbus Avenue entrance. Architect Santiago Calatrava designed the capsule for a design contest hosted by the editors of the New York Times in 1999. The capsule was sealed in 2000 to honor the beginning of the third millennium. Unlucky for us, the capsule, containing random objects representative of the third millennium, won’t open until the January 1, 3000.

In our previous behind the scenes exploration inside the artist studios where the dioramas are created, artist Jack Cesareo told us the American Museum of Natural History has one of the city’s longest hallways. It stretches from Columbus Avenue to Central Park West.

Next, discover vintage photos of the 12 Oldest NYC Museums, The Top 10 Secrets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Top 10 Secrets of the Guggenheim Museum in NYC. Get in touch with the author @sgeier97.

Subscribe to our newsletter