✨You Can Touch the Times Square New Year's Eve Ball!

Find out how you can take home a piece of the old New Year's Eve ball!

We previously brought you the hidden history of Washington Square Park, but now get a closer look at one of the park’s and city’s most famous monuments: the Washington Square Arch. Standing at the north side of the park, it was dedicated on May 4, 1895, to George Washington as the first president of the United States. The arch has stood in this spot for over 100 years presiding over the park’s colorful and ever-evolving culture and history. Here are the top 10 secrets of the Washington Arch.

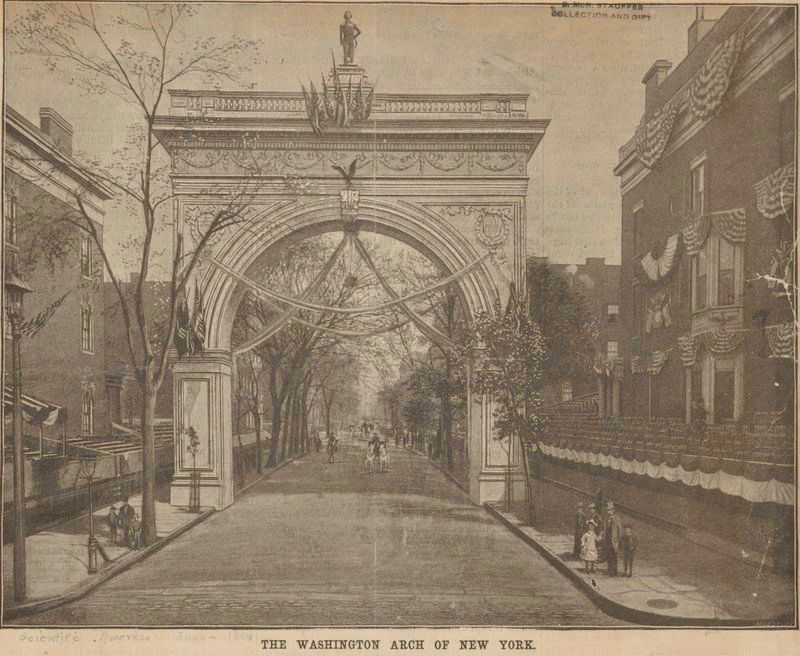

Before the marble arch was built in 1892, there was a temporary wooden arch erected in 1889 to celebrate the centennial of President George Washington’s inauguration (similar to another temporary arch at Madison Square Park). The arch, campaigned by William Rhinelander Stewart, was only supposed to be built temporarily for the celebration. Stewart, a wealthy resident of the area convinced other wealthy residents of the area to contribute funds to build this memorial, and brought in Stanford White, of the famous firm McKim Mead & White for the design.

On April 30, 1889, the wooden arch was decorated and lit up for the centennial. To build and decorate the whole thing cost $2,700, which is about $71,000 today.

The temporary arch became very popular and sparked a new campaign that brought in $150,000 (for a more permanent arch. And so in 1890, the marble arch in Washington Square Park that we are all familiar with today, still stands albeit a few feet south of where the original stood.

In 1917, a group of so-called “Bohemians” led by artists Marcel Duchamp, John Sloan and poet Gertrude Drick broke into the arch, climbed to the roof using the interior stairs and declared it the independent republic of New Bohemia. The all-night picnic involved Japanese lanterns, cooking, firing cap pistols and launching balloons. According to John Krawchuck, Director of Historic Preservation for the City of New York Parks & Recreation Department, “they had a picnic and a party and drank tea late into the night.” Though there was probably something a little stronger than tea in their drinks.

Along with drinking “tea” and staying up all night, Gertrude Drick read a proclamation she wrote declaring Washington Square to be a free and independent state, while John Sloan did an etching of the group. The group became known as “The Arch Conspirators.”

On the north side of the arch facing 5th Avenue are two statues of George Washington. On the east side stands Washington as Commander-in-Chief, Accompanied by Fame and Valor, or Washington at War, commemorating his time as general of the Colonial Army in the War of Independence. It was completed in 1916 by Hermon MacNeil. The statue on the west side of the arch was completed by Alexander Stirling Calder in 1918. It is called Washington as President, Accompanied by Wisdom and Justice (or Washington at Peace) denoting his time as the first president of the United States.

These two statues were added to the arch in their respective years of completion. Basically, they were not a part of the original arch of 1889, nor were they there when the permanent marble one was dedicated on May 4, 1895. Sadly, both the faces of statues suffered from a lot of erosion since cars became heavily used in the city. But following a full restoration and conservation of the arch campaign in 2002, the faces of Washington were re-carved and whole arch was rededicated on April 30, 2004.

The last car driven through the arch was in 1958 after the park officially became closed to cars after much campaigning.

See more on cars in the city, check out 10 Forgotten Examples of NYC’s Old Car-Centric History.

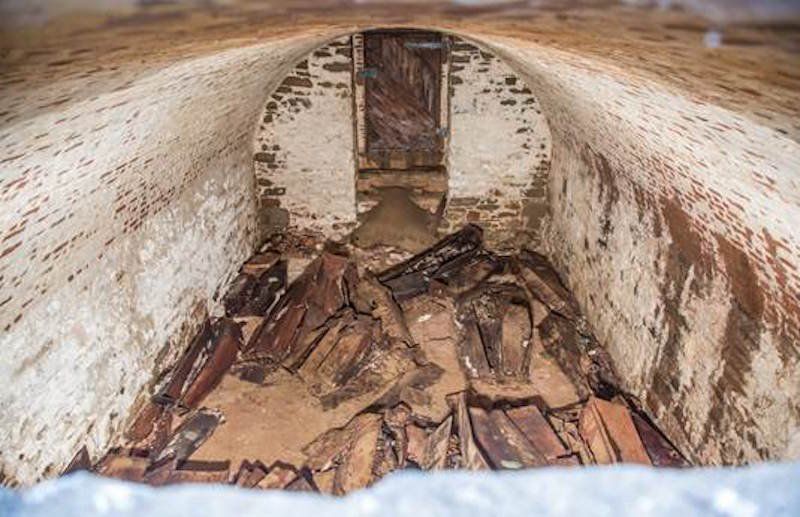

In 1890, when construction on the new arch began, first a part of the land had to be cleared, and the ground had to be broken to build the foundation the arch would stand on. But after just a short 10 days, construction was stopped when workers found skeletal remains underneath the area of the park. That was only 10 feet underground. After going down another two feet, every shovel full of dirt contained skeletal remains.

In the early years of the park following the Revolutionary War, the founders of New York City designated a few plots of land around the city as “potter’s fields,” public burial grounds for the poor who died mostly from yellow fever. Washington Square Park was one of them. However, one resident claimed that the potter’s field was only in the southern section of the park, not the north where the arch is. After an excavation was done, the resident was proven right after the discovery of a headstone from 1803 in the north side determined that area in particular to be an old, formal German cemetery.

Although work resumed, the issue of class distinction did not leave. In fact, the area had been slowly transforming into an area for tenements for the poorer population. When the cornerstone of the arch was laid on May 30, 1890, in front of an audience of 6000, Chairman of the Citizens Committee on Art, Henry Marquand proclaimed “It is true that the neighborhood may be all tenement houses in a few years. But have the occupants of the tenements no sense of beauty? No patriotism? No Right to good architecture?”

What else is buried underneath the city? Check out what NYC’s Former Cemeteries Are Now and 5 Notable Archaeological Sites in Manhattan.

Stanford White, the designer for the Washington Square Arch pulled from multiple inspirations, Roman architecture and the Arc de Triomphe in Paris that was built a about 50 years before, being the two most visible influences. White looked to make this one more modern and simple than the one in Paris, but he did also make sure to incorporate more antique elements into the design including allegorical figures, bands of decorative motifs, and wreaths of laurel.

Using White’s design, Frederick MacMonnies did all the relief sculpture work and Phillippe Martiny designed the eagles sitting on the north and south perches of the arch. The reliefs behind the two Washington statues are the allegorical figures some of which are represented by various Greek gods (for example, Wisdom to the left of Washington is Athena).

Fun fact: the arch was designed pro bono by Stanford White! Next, get a look Inside the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

Once used as an NYC Parks office, access inside the arch and its roof are restricted and closed to the public. A few have been lucky enough to enter using the small, dwarf-sized door on the arch’s western facade. The inside is fairly tight with a winding 102-step spiral staircase.

The staircase is made of Gustavino tile, the same tile that was used on the ceiling of the Oyster Bar at Grand Central Terminal. The staircase and roof access were never meant to be open to the public, the staircase especially was put in place solely for maintenance purposes. The roof is very fragile so NYC Parks tries to limit movement up there to prevent water from leaking in the arch.

For now, NYC Parks brings people in more official settings for interviews, so they are the ones who take the pictures and bring the arch’s hidden interior out the the public. Last year, NYC Parks broadcasted a live Periscope video of an exploration inside and atop the arch.

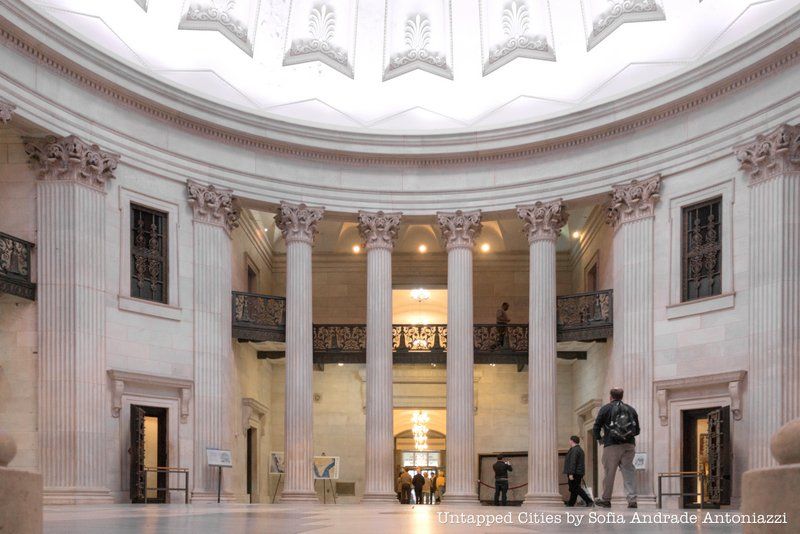

The arch is constructed out of marble from a now-closed quarry about 21 miles north of New York City in Tuckahoe, Eastchester. Quarrying in Tuckahoe ceased in 1930 which would cause some problems when it came to restoring the arch later on in 2001.

So how did the city get around that problem? Interestingly enough, pieces of Tuckahoe marble were being used as fill when the road was dug up for improvement during construction of the Taconic State Parkway. These pieces of marble were unneeded and just provided fill, so they were salvaged and used in the intense restoration project in 2002.

Tuckahoe marble was not only used for the Washington Square Arch, it was also used to build Federal Hall and St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Before 1980, arch was extensively covered in graffiti. In the 1990s the Parks Department went through intense efforts to clean the arch of its graffiti and proceeded to coat it with an anti-graffiti coating to prevent any more vandalism. Mr. Krawchuk from the Parks Department in an interview with the Wall Street Journal said “the messages were fascinating as we were taking off layers of paint […] Viet-nam era stuff.”

On May 4, 1980, artist Francis Hines made the Washington Square Arch the subject of an art project in which he wrapped the arch in 8,000 yards of polyester nets. Hines frequently uses ropes and fabric to wrap large objects, where the tension created by the ropes represents the “human struggle to free itself from restricting forces.”

The cloth used on this arch was secured by 3/8-inch cable and hand-fabricated steel fixtures. The cloth covering the arch stayed on through May 10th of that year. It served as a central point in the community movement to improve and restore Washington Square Park and the arch. The artist Ai Wei Wei has also created an installation focused on the arch.

Despite what you may think, the Washington Arch itself is not a New York City Landmark. It is, however, part of the Greenwich Village Historic District as designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in April 1969. An interesting fact though, the 2004 arch restoration effort received awards from both the Greenwich Village Historical Society and the Lucy Moses Preservation Award from the Landmarks Conservancy.

For more, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Washington Sqaure Park and 8 Monumental Arches of NYC: Washington Square Park, Grand Army Plaza, Manhattan Bridge

Subscribe to our newsletter