Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

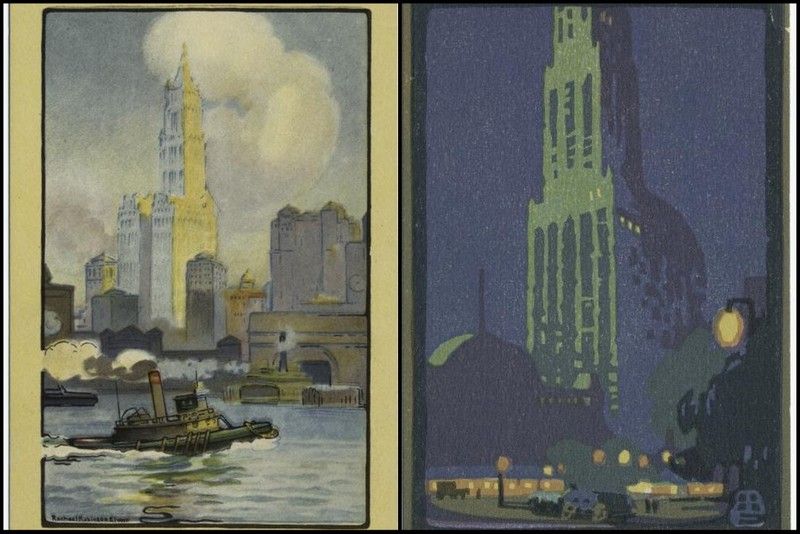

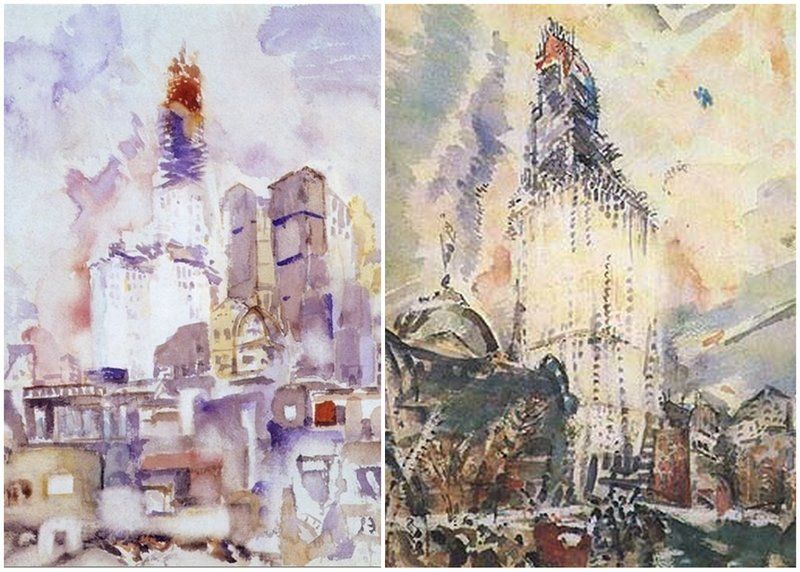

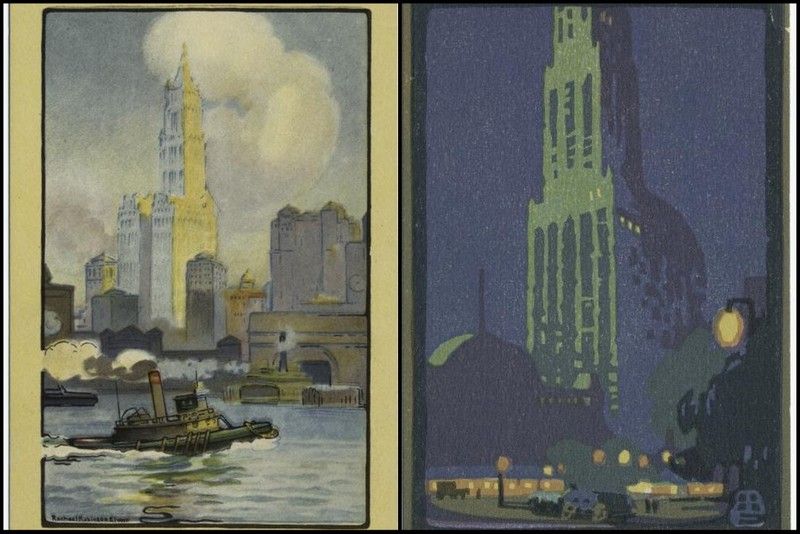

Two images of the Woolworth Building (left, 1914; right 1916) by Rachael Robinson Elmer

As skyscrapers sprouted in ever increasing numbers in New York, Chicago, and other cities around the turn of the last century, many people first viewed them as ugly intrusions lacking the charm and grace of more traditional building types. However, new design approaches, specifically suited to the the skyscraper, were developed by architects such as Louis Sullivan and McKim, Mead, and White. As a result, skyscrapers came to be seen as structures that also could be things of beauty.

With this new aesthetic, many artists created works of arts featuring skyscrapers with positive, uplifting associations. While American artists of the mid-nineteenth century had depicted landscapes of the Hudson River valley and the west, in the early twentieth century the new man-made mountains and canyons of the urban frontier filled many an artist’s canvas.

Although the first building considered to be a skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building completed in Chicago in 1885, New York soon amassed the greatest concentration of these high rise buildings, creating an iconic, ever changing skyline. We present here ten artists who found their muse among the skyscrapers of New York as these buildings became defining images of the city.

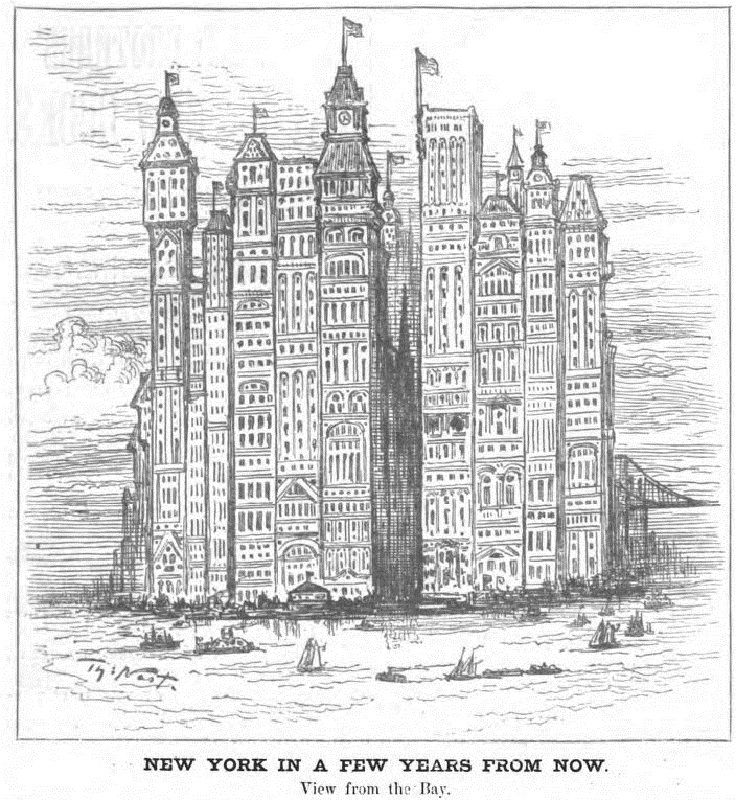

Harper’s Weekly, 27 August 1881, by Thomas Nast

Even before “skyscrapers” existed, they were the subject of an artist’s fancy.

In 1881 political cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902) drew “New York In A Few Years From Now: A View From the Bay” for Harper’s Weekly. It was a prescient view of a future Lower Manhattan, teeming with tall, slender towers. It is unclear if Nast, a German immigrant known for his sharp edged opinions and his crusade against Boss Tweed, intended this image as a future to be weary of or one to be embraced.

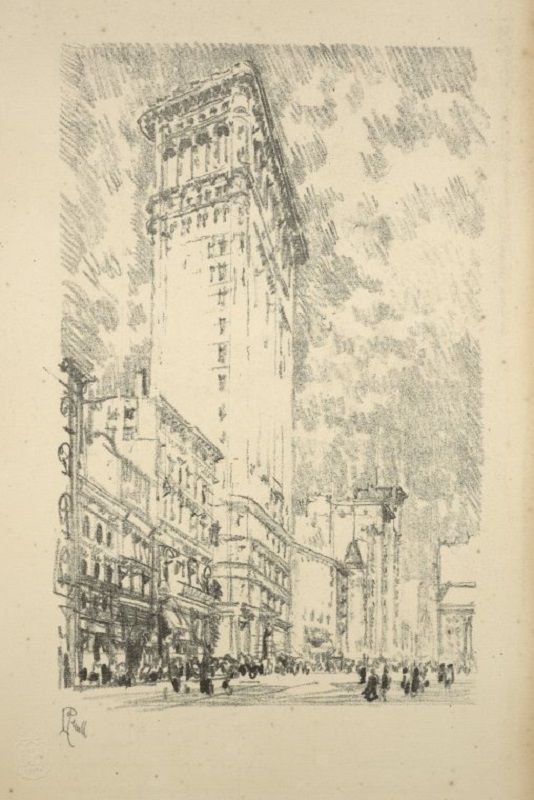

“Flatiron Building From Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Seventh Street” (ca. 1904-1908) by Joseph Pennell Via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

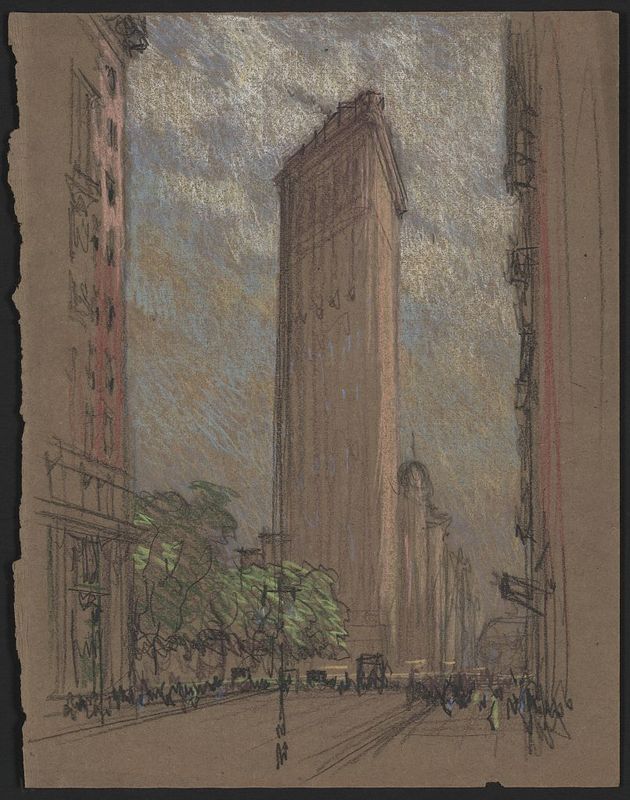

One of the first skyscrapers in New York that captured the public’s imagination was the Fuller Building, located on the triangular block at Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and 23rd Street. Due to its distinctive wedge shape it immediately became known as the Flatiron Building. Designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, the building, with its dramatic setting at a crossroads intersection and facing Madison Square Park, also became a favorite of artists.

“The Flat Iron” (1904) by Joseph Pennell Via NY Public Library Digital Collections

One of those under the spell of the Flatiron was Joseph Pennell (1857-1926), a Philadelphia native who lived in London for many years before moving to New York. His Flatiron works are among his most famous in a decades long career that included other New York scenes as well.

Woolworth Building by John Marin. Images from Wikimedia Commons (left, right)

Although born in Rutherford, New Jersey, just a few miles from New York, John Marin (1870-1953) did not arrive on the city’s art scene until he was in his early 40s. After working as an architectural draftsman, studying art in Philadelphia, and spending several years in Paris, he made a breakthrough thanks to art gallery owner Joseph Stieglitz who displayed and promoted Marin’s work.

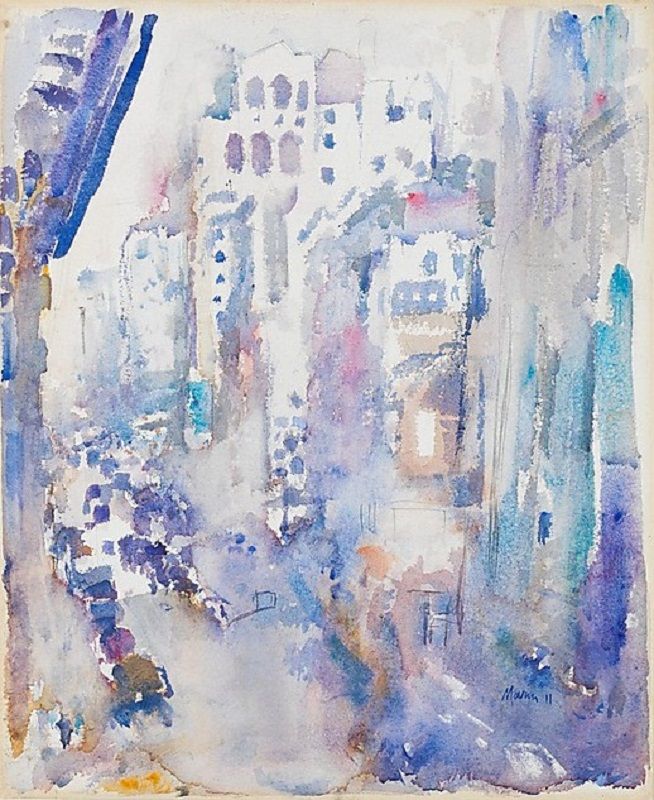

“From the Window of “291,” Looking Down Fifth Avenue” (1911) by John Marin. Via Wikimedia Commons

In New York, Marin found a muse in the city’s skyscrapers, which suited his unique style that has been variously described as post-Impressionistic, a hybrid of Impressionist, Cubist, and Expressionist, and early Modernist. Although his fame has ebbed since his death, he was considered a major artist of his time. “Marin is a visionary,” wrote art critic A.E. Gallatin in 1922, “his work always so beautifully organized and so superb in design, is full of mystery.”

One of Marin’s most renowned works, displayed here, “From the Window of “291,” Looking Down Fifth Avenue,” shows a view from 291 Fifth Avenue, home to Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery. Other skyscraper subjects included the New York Telephone Building, a “wedding cake” style building with a massing that lent itself to his Cubist influenced approach.

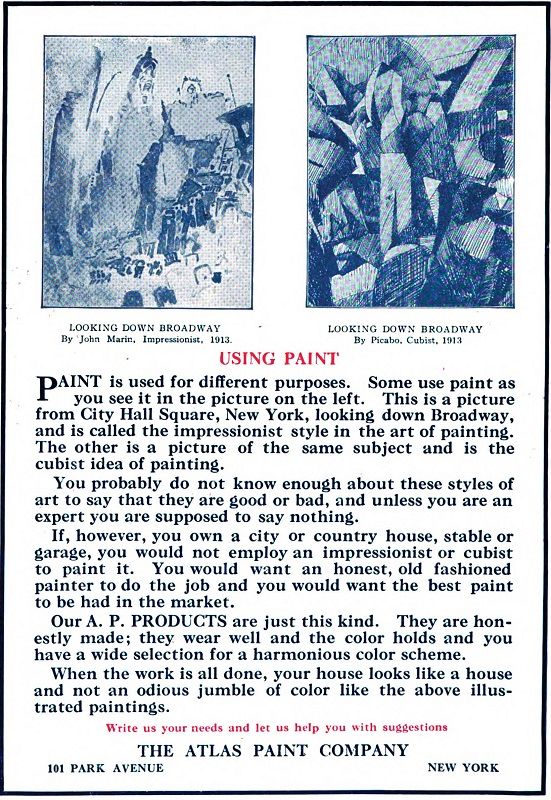

Advertisement in the The Architectural Record, August 1913

Marin’s skyscraper work was even displayed in advertisements for building paints, though his work was dismissively referred to as “an odious jumble of color.”

Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986) had a long and prolific career as an artist, painting a wide variety of subjects. She was the first woman to have a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and was one of the most influential twentieth century American painters. While her Precisionist pieces featuring skyscrapers and other New York subjects represent a small portion of her oeuvre, they are among her most celebrated. These include “Shelton Hotel New York No. 1,” where she lived with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz (the same Stieglitz who exhibited Marin’s work). The building is now the Marriott East Side.

The Shelton also provided a vantage point for O’Keefe to create “Radiator Building at Night, New York.” She painted the office building, now the Bryant Park Hotel, from her high rise studio in the Shelton. She had come to the big city from a small town in the Midwest but found her muse in the New York skyscraper.

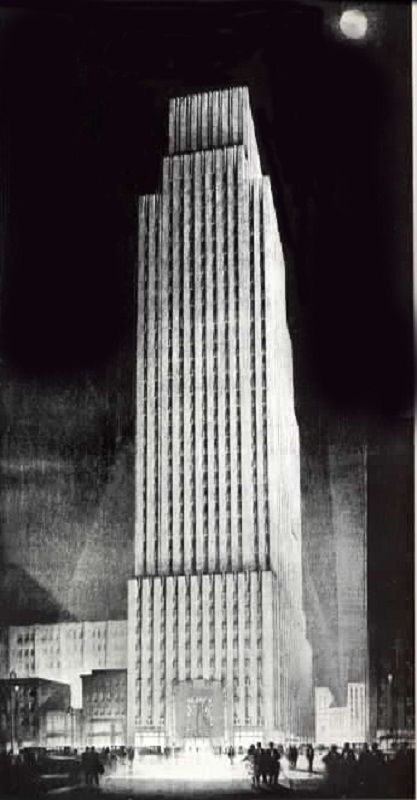

“New York Daily News Building” (1930) by Hugh Ferriss. Via Wikimedia Commons from Dover Publishing.

Ostensibly, Hugh Ferris (1889-1962) was a delineator, a person who created architectural renderings for proposed buildings, rather than an “artist.” Although his skyscraper drawings were done as commissions from architects, he executed his renderings with an artistic touch that made them a cut above the usual. The St. Louis native began his career working in the office of architect Cass Gilbert, where he created renderings for the Woolworth Building. He soon struck out on his own and worked with many firms.

Ferriss’ subjects included the News Building in Midtown, an Art Deco icon, and the proposed but unbuilt Convocation Tower at Madison Square Park. Both typify his strengths, including using depth and shading to give buildings three-dimensional character and providing rich atmospheric settings. The Convocation Tower piece also shows the neighboring Metropolitan Life Tower, demonstrating that he was equally adept at illustrating existing buildings.

Left: “The Woolworth Building From the Ferry” (1914) Right: “Woolworth Building June Night” (1916). Both by Rachael Robinson Elmer. Via NY Public Library Digital Collections

Another skyscraper that inspired artists and which was viewed as a work of art itself was the Woolworth Building. Besides artists such as John Marin, Vermont native Rachael Robinson Elmer (1878-1919) found a muse in Cass Gilbert’s 1913 creation. While studying at the Arts Student League she had became enchanted by New York and found an outlet for her art through mass produced postcards. She produced two sets, issued in 1914 and 1916, which sold well and although her works were signed, her images were more well known than her name.

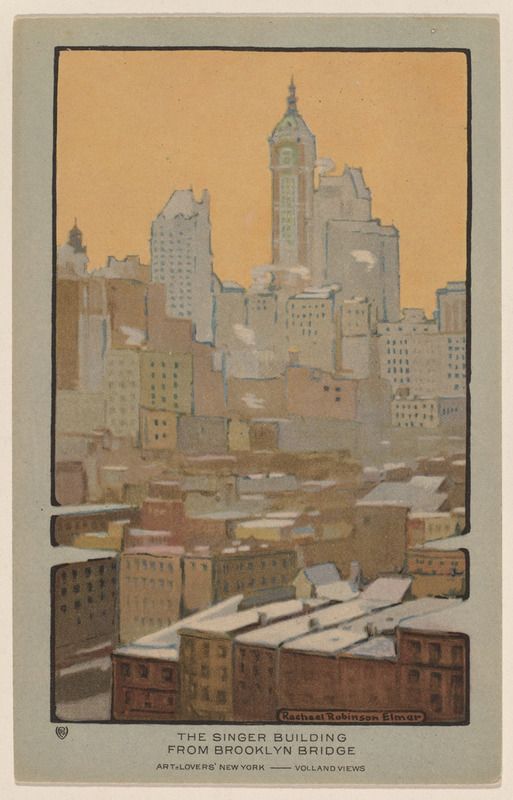

“The Singer Building from Brooklyn Bridge” (1914) by Rachael Robinson Elmer. Via NY Public Library Digital Collections

In addition to the Woolworth Building, as part of the “Art Lovers New York Series,” Robinson Elmer also illustrated a number of other New York scenes, including the Singer Building, the tallest building in the world upon completion in 1899 and the tallest building ever demolished by its owner, in 1968. Sadly, she died in in the influenza epidemic of 1919.

Join us on an upcoming VIP tour of the Woolworth Building, usually off-limits to the public:

VIP Tour of the Woolworth Building

“Sky Line and Waterfront Traffic as Seen from Manhattan Bridge” (ca. 1938) by Louis Lonwick

Interestingly, all of the artists featured here came to New York from somewhere else. In the case of Louis Lonwick (1892-1973), he came the furthest, emigrating from Ukraine as a teenager. He focused much of his art on skyscrapers and how they fit into the wider urban tableau. As with Georgia O’Keefe and Charles Sheeler, much of his work is associated with Precisionism.

In “Roof and Sky,” Lozowick links what appears to be a roof vent, a rather humble feature of a low-rise building, though shown in a way that accentuates the attractiveness of its rounded shape, with the tapered form of the Empire State Building in the distance. “Hanover Square,” shows a vista with cars and an elevated train in the foreground and skyscrapers beyond. These structures contrast, but there is a connection.

Lozowick also created murals of the Lower Manhattan skyline and Triborough Bridge for the James A. Farley Post Office in Manhattan, one of many publicly-commissioned art works in postal facilities during the New Deal.

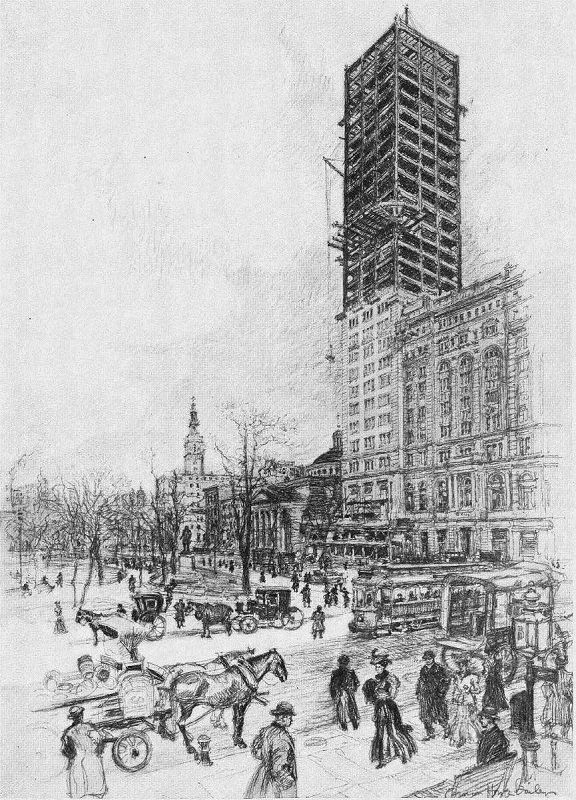

“As New York Climbs Skyward” by Vernon Howe Bailey, Harper’s Weekly, 1 February 1908

A native of Camden, New Jersey who attended the same Philadelphia art schools as Charles Sheeler, Vernon Howe Bailey (1874-1953) settled in New York after stints in Boston and London. Primarily an illustrator for newspapers and magazines who specialized in drawings of architecture and street scenes, Bailey was similar to Ferriss in that he was required to be faithful to the details of his subjects but nevertheless imbued his drawings with impressionistic influences that elevated him above most of his peers.

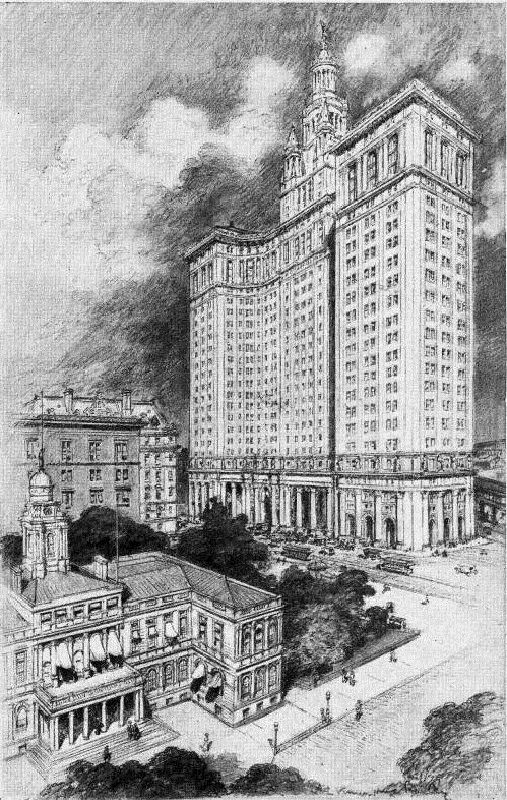

“New York’s City Hall of To-morrow,” by Vernon Howe Bailey, Harper’s Weekly, 7 October 1911

His drawings shown here are of the Metropolitan Life Tower at Madison Square Park under construction, with the second Madison Square Garden in the background, and a rendering of the Municipal Building in Lower Manhattan and nearby City Hall, showing the contrast between early nineteenth and early twentieth century civic architecture.

Architect Cass Gilbert, who wrote the introduction to Bailey’s 1928 book Skyscrapers of New York, observed that Bailey “with skillful, subtle line and well-accented light and shade, has shown in black and white that the skyscrapers of New York form the most picturesque group of buildings in the whole world.” Of course, as one of New York’s foremost skyscraper architects, Gilbert may have been a bit biased.

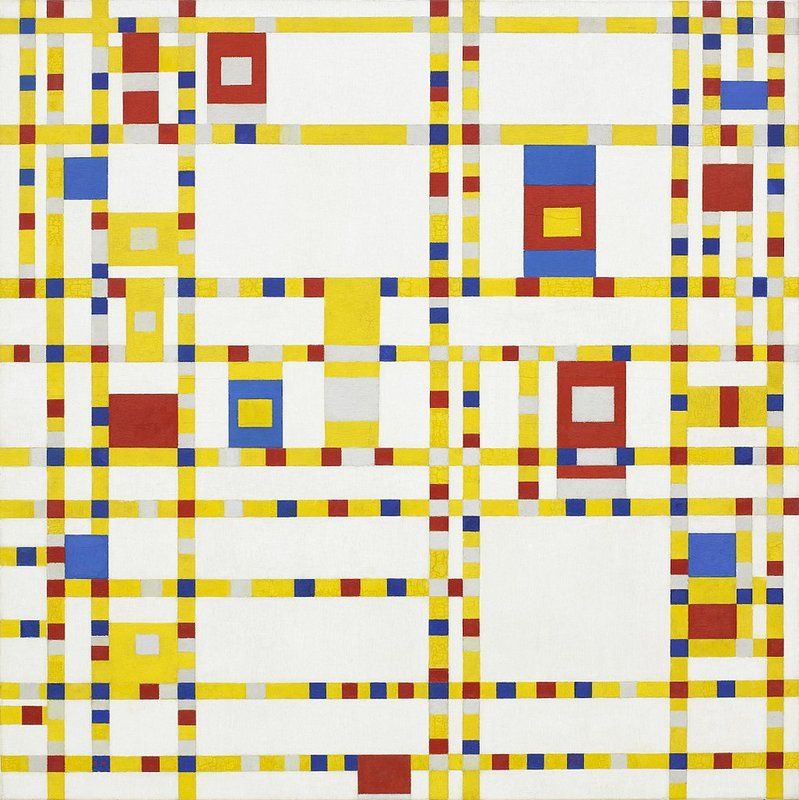

“Broadway Boogie-Woogie” (1943) by Piet Mondrian from The Museum of Modern art via Wikimedia Commons.

“Broadway Boogie-Woogie” (1943) by Piet Mondrian from The Museum of Modern art via Wikimedia Commons.

As a Dutchman acclaimed for his abstract painting, Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) seemed unlikely to take on New York and its urban form as a subject. Many of his works consisted of vertical and horizontal lines and rectangles with a palette limited to primary colors, black, and gray set against white backgrounds. In doing so, he created a widely influential design aesthetic, a style he dubbed Neo-Plasticism which he adopted after abandoning representational forms in the 1910s.

With war in Europe, Mondrian arrived in New York in 1940. His new home was not only a refuge, but, as with so many other artists, New York also became his muse. The city was a place where his geometric style could represent physical characteristics. In Broadway Boogie-Woogie, his intersecting lines and color rectangles evoke the city’s rectilinear street grid, skyscrapers facades, and the lights of the Great White Way. Completed in 1943, it also turned out to be his swan song as he died the following year while working on a new piece, Victory Boogie-Woogie, which further explored these themes.

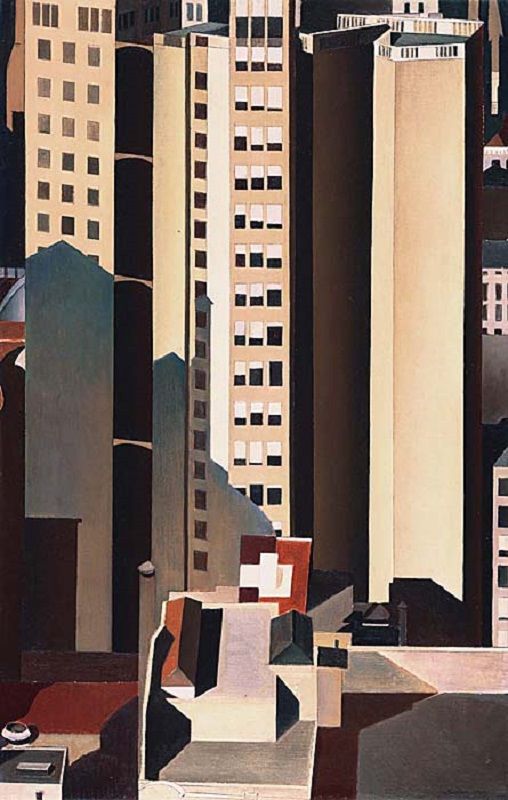

“Skyscrapers” (1922) by Charles Sheeler. Via Wikimedia Commons

Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) was a Philadelphia native who studied at the School of Industrial Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in his hometown. He initially pursued painting and photography, but with the encouragement of Alfred Stieglitz he put his camera aside and moved to New York.

Similar to Marin, many of Sheeler’s pieces focused on built structures, including skyscrapers. Stylistically, however, he differed from Marin in that he was a leading practitioner of the Precisionist approach, a US-based realist style that emphasized geometric shapes and the connections between people, architecture and other objects of the “Machine Age.”

Next, read about the self-referential skyscraper costumes worn at the 1931 Beaux Arts Ball, Hugh Ferriss’ drawing of future New York, and the top 10 Secrets of the Woolworth Building.

Subscribe to our newsletter