Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Williamsburg Bridge is a suspension bridge in New York City over the East River, connecting Brooklyn’s Williamsburg area to the Lower East Side in Manhattan at Delancey Street, and was the second one built across the East River. Built in 1903, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time at over 1000 feet long (a title previously held by the Brooklyn Bridge). Today it is one of the busiest carrying vehicles between the city’s two boroughs. Previously, we brought you 10 fun facts about the creation of the bridge, but there’s plenty of interesting history surrounding the structure upon its completion. So, we’ve compiled a list of the top 10 secrets of the Williamsburg Bridge.

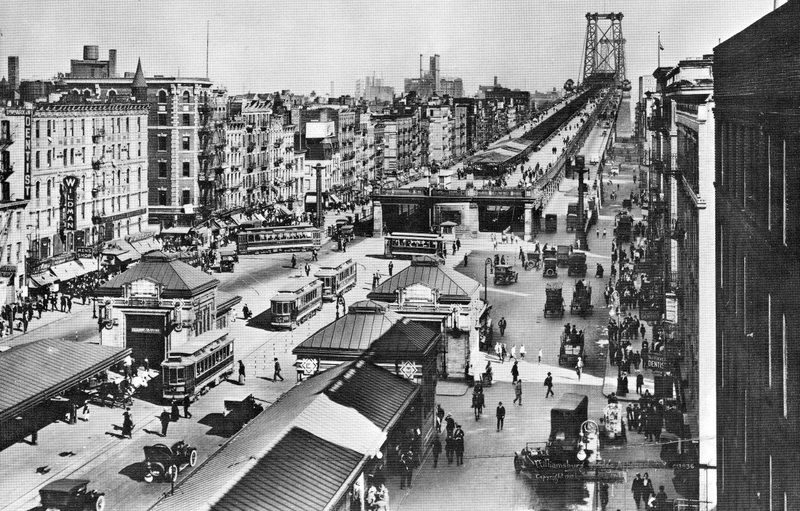

The Williamsburg Bridge opened on December 19, 1903 to pedestrians, bicycles, and horse-drawn carriages. The New York City subway system did not open until October 27, 1904, almost one year later. But that still leaves four years of no trains running service across the bridge. This was due to the surrounding complications between the Greater New York Area and the privately owned railway companies. The bridge originally designated the inside lanes for street cars and the outside lanes for buggies. But once street cars became obsolete, the inside lanes were converted for automobile traffic.

As the increase in automobile usage increased, the bridge had to be adjusted with the increase in traffic, which ultimately led to the 8-lane expansion in the 1920s. The trolley’s, or elevated city rail lines, were then able to run across the river. The original rapid transit tracks in the center of the bridge were used by the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company elevated rail, but today, the J/M/Z subways use the bridge.

A notable remnant of the Williamsburg trolley remains at the Essex/Delancey street stop today, which the Lowline hopes to turn into the world’s first underground park. Service from Brooklyn to Manhattan back then stopped through the Williamsburg Bridge Rail Terminal at Essex and Delancey.

Next, check out the Trolley Ghosts of the Abandoned Essex/Delancey Williamsburg Bridge Rail Terminal in NYC.

View from Delancey Street in Manhattan in 1919. Photo in Public Domain from Wikimedia Commons.

The Long Island Rail Road used to run across the bridge on a separate elevated extension, though it did not last long since that service was shut down in 1916. As the bridge became more well equipped to handle trains and cars, the LIRR service did not last with the growth of the subway system.

The LIRR line across the Williamsburg Bridge split from the existing Atlantic Avenue line, heading northwest on the former Broadway Elevated Line (today’s J/M/Z lines), crossed the bridge to Manhattan, and then continued towards Chambers Street.

For 12 years, from 2001 to 2013, Marty Markowitz, a passionate Brooklynite, served as the Brooklyn Borough President with a personal touch, celebrating the borough in every way possible. Known for his wild ideas, you might recall when Markowitz decided to put fun signs on the bridges connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan (or vice versa, depending on the way you see it). The Williamsburg Bridge received the one pictured above, proclaiming “Oy Vey!” to those leaving Brooklyn and entering Manhattan.

A few other quirky signs were put up at the entrance of the lower and upper levels of the Verrazano Bridge reading “Leaving Brooklyn/ Fuhgeddaboudit!” following the popularity of the “Welcome to Brooklyn” signs Markowitz put up previously with phrases like “How Sweet It Is” and “Believe the Hype.” It was a person’s response to the “Fuhgeddaboudit!” sign that prompted Markowitz to create the “Oy Vey!” one.

According to the New York Times, a man called in and complained to Markowitz that the sign was anti-Italian, asking him “You’re Jewish Mr. Markowitz. How would you like a sign that says, ‘Leaving Brooklyn, oy vey’?” Markowitz’s response? “What a great idea. Thank you.”

However, “Oy Vey!” created tension with the City’s Department of Transportation, telling him that the signs were unnecessary and distracting. According to policies of the Federal Highway Administration, signs are mandated to offer useful information. Iris Weinshall, commissioner of the Department of Transportation at the time said, “‘Oy vey’ doesn’t give you any information.”

It should also be noted that studies have not yet shown if the number of accidents increased since the signs went up.

In the first decade of the Williamsburg Bridge, engineers began to notice that the bridge was starting to sag from the heavy traffic. The situation was remedied by two additional supports that were added under each of the unsuspended side spans, and there was additional steel put into the deck to support the heavier subway cars.

Originally, Leffert Buck designed the bridge so that traffic would adapt to the bridge. But as the sagging incident showed, the new strengthening reports said the bridge need to adapt itself to traffic. Despite the sagging fix in the early 1900s, the bridge fell into a state of disrepair as early as 1964, with reports of rust raining down on pedestrians. By the 1980s, the situation had become critical and it was clear something had to be done.

Following an inspection in 1988, it was revealed that there was corrosion in the cables, beams, and steel supports. The bridge was closed to all car and train traffic for almost two months while workers performed emergency construction. Shortly after, a panel of designers tried to figure out if rehabilitation or replacement was the way to go. Rehabilitation costs were about $250 million, and replacement costs hovered around $700 million.

Part of the reason why the bridge had fallen into such disrepair was because Leffert Buck had it built without galvanizing the wires. Galvanizing is a kind of coating process that prevents metal from rusting, while still allowing it to oxidize. The Williamsburg is also the only bridge in New York City to not be galvanized.

In 1988, the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) decided to repair the bridge while still allowing traffic to cross as it would have the least negative impact on the surrounding communities and those who used the bridge. So in 1991, the NYCDOT began the 15-year, $1 billion reconstruction. Today, the bridge is stronger than it ever was.

Following the attacks on September 11th, 2001, traffic in and out of New York City was put to a stop. For the next week, the Williamsburg Bridge remained closed to all except emergency vehicles. Afterwards, new restrictions were imposed on the bridge’s HOV lane as part of a large-scale effort to reduce congestions below 63rd street. The HOV-restrictions remained in place on the Manhattan bound side until November 2003.

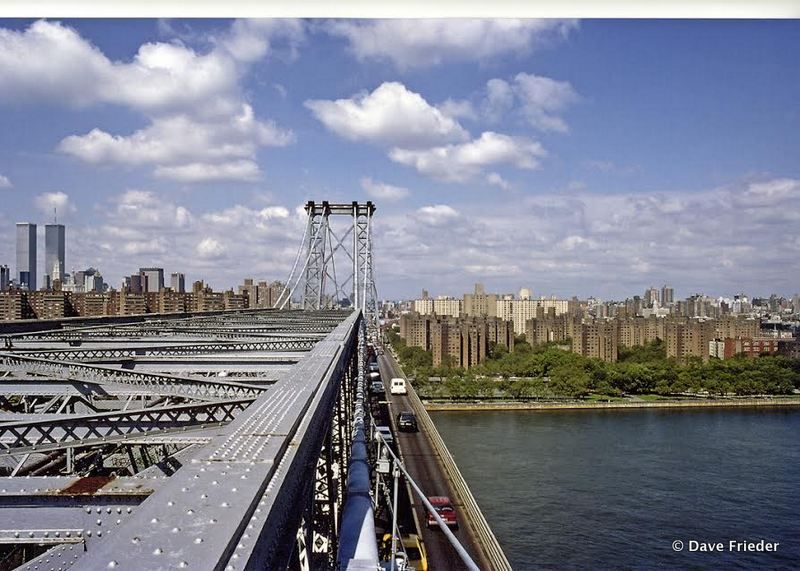

The Williamsburg Bridge is widely regarded as one of the city’s ugliest bridges. In 1903, Scientific American reported that it was “destined to be more popular on account of its size and usefulness than its graceful lines.” In fact, Supported by steel towers instead of the beautiful neo-gothic stone stone towers like the Brooklyn Bridge, the Williamsburg, though it looks more unattractive, took half the time build (7 years as opposed to 13 years for the Brooklyn Bridge).

Despite the fact that the bridge may look more unattractive, the chief engineer, Leffert Lefferts Buck, used steel instead of stone because it was stronger and much lighter.It also proved very sturdy after a fire broke out on it in November 1902. The bridge survived with minimal damage, reinforcing the strength of this new architectural practice. Besides being sturdy at the time, the steel towers were basically the only structures that could support the incredible weight of the railways and roads.

Leffert Buck was said to be inspired by Gustav Eiffel’s Eiffel Tower in his design of the Williamsburg. Buck also perviously worked with Mr. Eiffel which could also account for the similarities. It should be noted that the Eiffel Tower was initially not well received either upon being built. As Scientific American put it, “Considered from aesthetic standpoint, the (Williamsburg) Bridge will always suffer by comparison to its neighbor, the Brooklyn Bridge.”

Fun fact: Leffert Buck went to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute with Washington Roebling, one of the architects of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Before the bridge was built, Williamsburg, Brooklyn was predominantly Irish and German, nicknamed “Kleine Deutschland” meaning Little Germany. Following the bridge’s completion, a mass migration of Jewish immigrants moved from the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side across into Williamsburg, causing previous residents of the area to move to Queens. The Williamsburg Bridge was during that time known as the “Jews’ Highway.”

The Williamsburg Bridge was names after Colonel Jonathan Williams, the grand-nephew of Benjamin Franklin, though his relation to the man was not what got a bridge and area of Brooklyn named after him. Born in 1751, Williams worked with Benjamin Franklin in Nantes, France, but it was his work back in the United States that earned him high recognition among his peers and high ranking members of the government, including two sitting presidents.

Williams served a distinguished career as a politician, military figure, businessman, and writer. The land of Williamsburg in today’s Brooklyn was named after him in 1802 by an investor who purchased the area, in honor of him being the one who surveyed the land.

Colonel Williams also designed strong fortifications on many buildings across New York City and Philadelphia. In fact, New York State put him in charge of constructing fortifications for New York City.

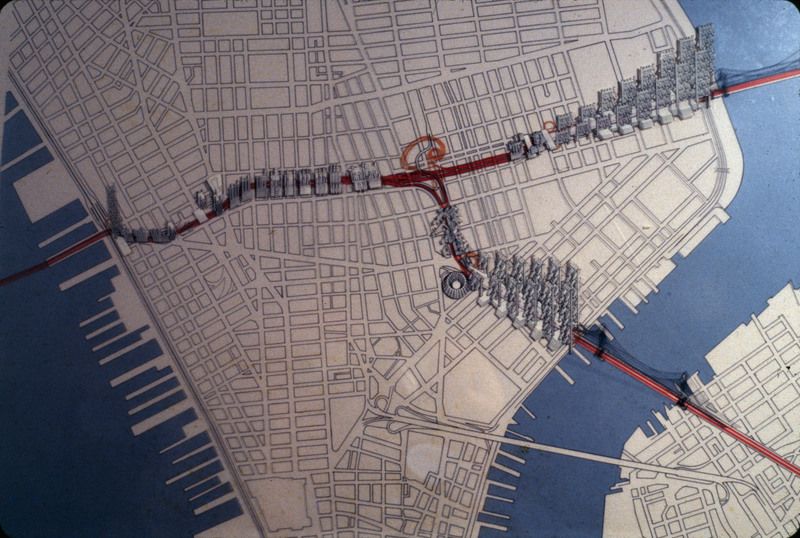

Red route highlights where the LOMEX would have gone. Image from Library of Congress

Among many of visionary infrastructure plans designed by Robert Moses in the mid 20th century, one of them was the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX), or Interstate 78. The plan would have connected the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges to the Holland Tunnel, cutting through SoHo and Little Italy. So had this expressway been realized, the Williamsburg Bridge would have obtained Interstate 78 designation.

The plans were canceled in 1971, but during the 1960s and early 70s, directional signs for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE, or I-278) posted I-78 signs for the Williamsburg.

For more on the LOMEX, see The NYC That Never Was: Robert Moses’ Lower Manhattan Expressway

When the bridge was originally built, there was a toll, presumably to levy the costs of maintaining it. But in 1910, the City of New York passed a law which removed and prohibited tolls that would finance the Williamsburg’s construction and maintenance. Since then, the bridge has remained toll free for all motor vehicles.

That almost changed in 2002, when Mayor Bloomberg was looking to sell the Williamsburg to MTA Bridges and Tunnels. By implementing a toll on this and other East River bridges, an estimated $800 million of toll revenue would be brought in annually. However, in order for something like this to go through, it needs to approval from the City Council and the State Legislature. Governor George Pataki killed the plan.

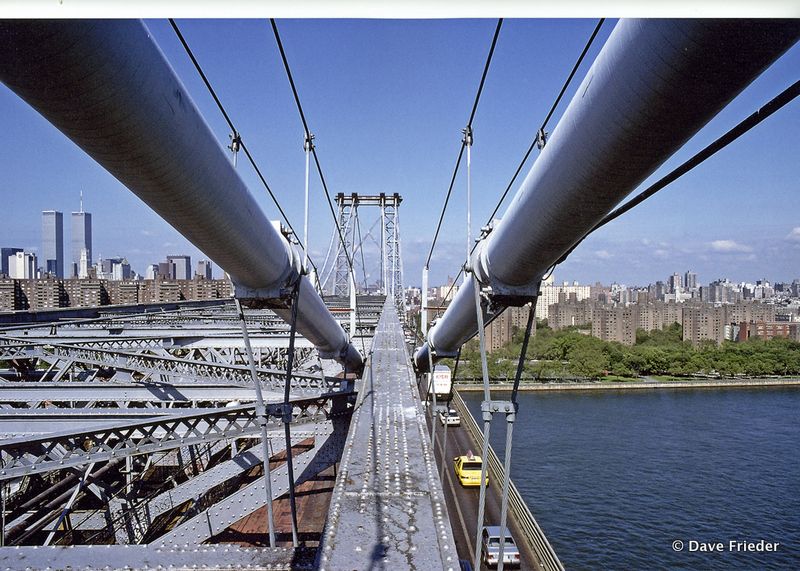

Aside from not galvanizing the wires, Leffert also used only one suspender rope to connect the deck of the bridge to two main cable ropes. What this means is that if that one suspender rope were to snap, you would lose the support of the two main cables. Only almost 90 years later during the rehabilitation of the bridge did the engineers do away with the one suspender rope, adding instead a suspender rope coming off of each main cable.

The shape of the steel going across the bridge horizontally has a kind of diamond shape to it, that is a “Lattice” truss, also known as a “Town” truss. Previously, the old Willis Avenue Bridge connecting the Bronx to Manhattan over the Harlem River, used to also have a diamond truss. But after it was replaced, the Williamsburg Bridge became the only one in New York City with a diamond truss. Additionally, since the trains run on the middle lane, the truss was able to be constructed at 40 feet, making it more stable.

The intense repair the bridge underwent beginning in 1991 had several issues that needed to be addressed. One of them included updating the deck. The original deck was made of 6 to 7 inch thick concrete, making it very heavy. It was replaced with what’s called an orthotropic deck, a kind of steel deck plate fastened transversely or longitudinally. This made the Williamsburg’s deck much stronger and lighter than the original concrete.

Next, check out 15 NYC Bridges Under Construction: Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queensboro, Williamsburg Bridges and the Top 10 Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Subscribe to our newsletter