How NYC Subway, LIRR, and Metro-North Responds to Snowstorms

Snow blowers, throwers, plows, and more specialized equipment help keep NYC moving in the snow!

Ever wonder what that castle-like building on Park Avenue on the Upper East Side is? Once one of the grandest of the armories in New York City, the Park Avenue Armory has a storied history and comes with a wonderful story of adaptive reuse. Like many institutional buildings in New York City, time and circumstances led the armory to fall into disrepair, and by the year 2000 it was named one of the 100 most endangered historic sites in the world by World Monuments Fund.

Luckily, it has since been revitalized through the efforts of the non-profit group Park Avenue Armory, and today opens its doors to a full calendar of exhibits and performances. In addition to its public facade, there is much unknown about the Armory. Here are ten facts you may not know about the Park Avenue Armory.

The Park Avenue Armory was built from 1877 to 1881 at a cost of $650,000 by the Seventh Regiment of the National Guard. This Regiment was made up of prominent Gilded Age family names that included Vanderbilt, Van Rensselaer, Roosevelt, Harriman, Livingston, and Morgan. Its roster included August Belmont Jr., the financier who helped build the city’s first subway line (and Belmont Track), and artists Thomas Nast and Sanford Robinson Gifford. Often referred to as the Silk Stocking regiment, this was the only privately funded armory – each room looking every bit as decadent as the near-by homes its members lived in.

In a recent lecture series, Military Historian and Park Avenue Armory Chairman, Elihu Rose described this elite band of men as having “easy arrogance – 100% attitude.”

Park Avenue Armory image. In public domain from New York State Military Museum

The original Park Avenue Armory was built in 1877-1881. In 1909, significant changes were made, adding a fourth and fifth floor, removing the bell tower, and giving the facade the feeling of a fortress. The armories of that time were looked upon as symbols of law and order, and it was felt that these changes represented that image.

Two men from the 53rd Army Liaison Team, stationed at the Park Avenue Armory

In 2010, a bus filled with National Guard just home from the Iraq war arrived at the Park Avenue Armory, greeted by friends and family. Although not quite the elite men’s club of old, they were the Seventh Regiment, renamed the 53rd Army Liaison Team of the New York Army National Guard. This group of between 25 and 30 men and women specializes in communications and calls the fourth floor of the Park Avenue Armory its home. The National Guard is no longer responsible for the upkeep of the building, which is now owned by New York State and they no longer use the 55,000 square-foot Drill Hall for marching exercising.

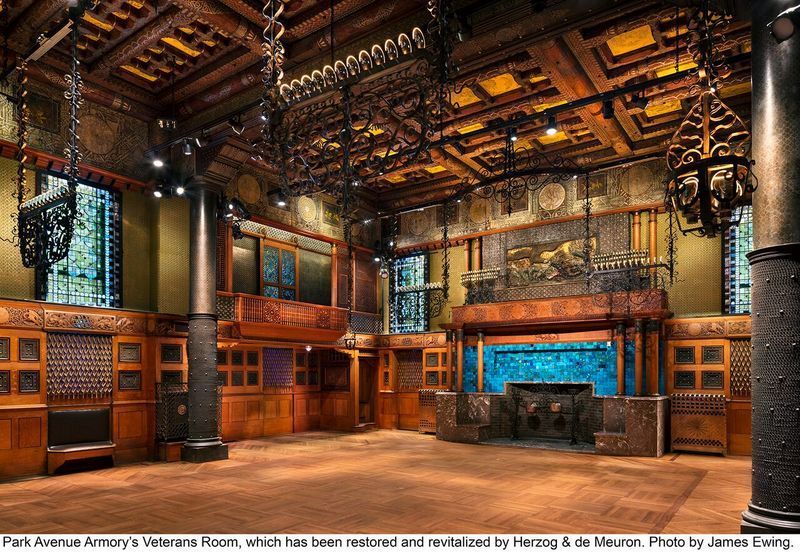

New York State has a $1 lease for the land under the Armory, which is owned by the city. This agreement dates back to 1870. A 99-year lease on the Armory was acquired by the Seventh Regiment Armory Conservancy in 2006. The non-profit group Park Avenue Armory has undertaken the exterior renovation and the enormous project of interior restoration one room at a time. When they first began their work, they found crumbling and water-stained ceilings, original flooring that had been covered up for years, over-painted walls, adding to what seemed like an overwhelming list of repairs and renovations. The estimated cost of interior projects is expected to be about $200 million.

Viewing a small patch of the original wallpaper in the Ladies Reception Room, yet to be restored

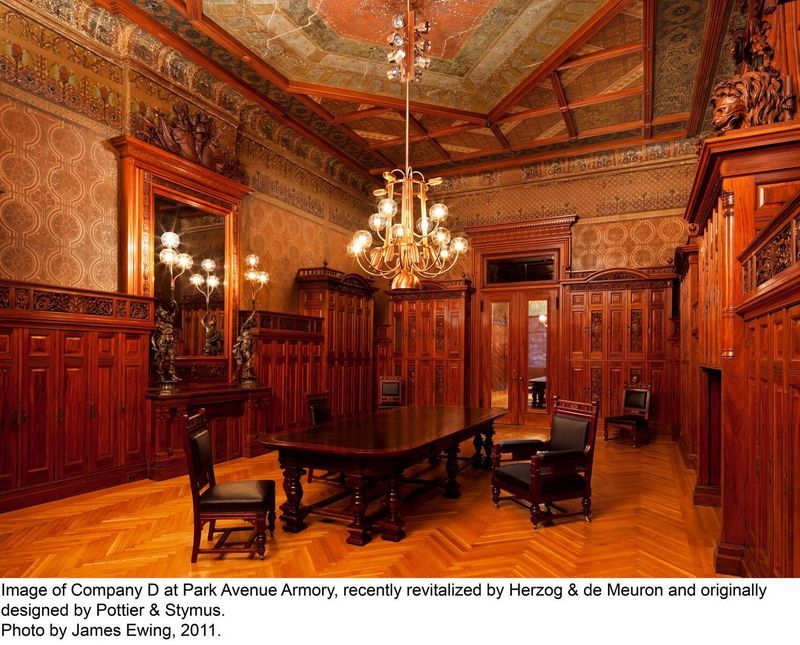

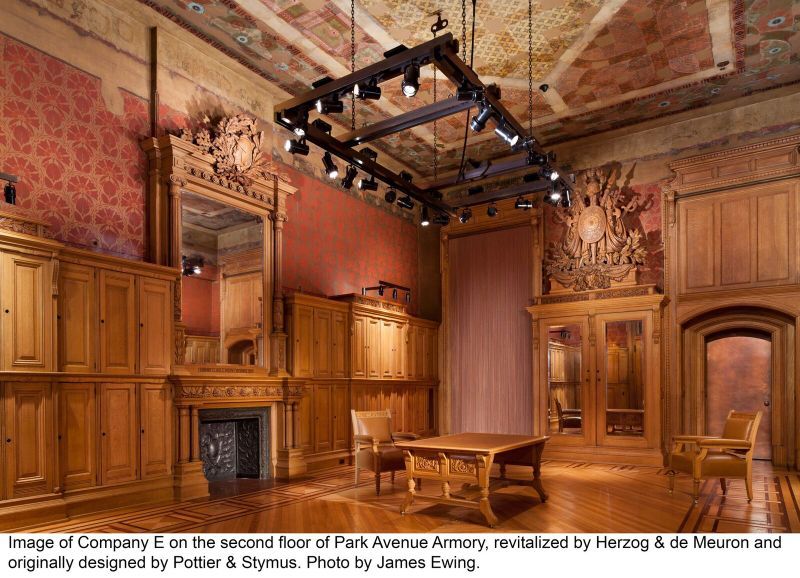

Private donors pay for the interior renovations. To date, four rooms have been completed. Company Rooms D and E were completed with money from one donor. The recently renovated Veterans Room was completed with donations from fifteen donors.

The second floor of the Park Avenue Armory houses ten Company Rooms and each room had a membership of 100 men. The memberships of these elaborate locker rooms were a family tradition, whereby generations took up membership in the Company Room of their fathers and grandfathers.

When the renovations of the Company Rooms began, it was discovered that the lockers were filled with more than dirty sneakers. Every manner of wartime paraphernalia came tumbling out, from ornate uniforms to training grenades. But the elite member of the Seventh Regiment were mostly charged with keeping the peace at home, dealing with local issues like the the Brooklyn Trolley Car Strike of 1895 or the “Croton Dam Strike of 1900, attending parades, civic receptions and the opening of monuments. They guarded against violent labor confrontations, fights over religious differences, ethnic differences and political upheavals. The regiment didn’t see battle until 1918, but they served on guard duty in the Civil War and the War of 1812.These rooms are now used for artists-in-residence, educational programs, and workshops.

There was a gym on the third floor used by the Seventh Regiment, and its constant use created cracks in the ceilings of the rooms below it. We viewed the cracks in two of the Company Rooms, D and E, visible in the photo above. While we were there, we met a fellow who was a past-member of Company Room A in the 1960s, and he spoke of the Company Room servants who would shine their boots.

A past member of Company Room A

The Ladies Reception Room named for Mary Divver. Image via Library of Congress

The Ladies Reception Room is named for a Mary Divver, who was an orphan adopted by the Seventh Regiment in 1852. She was the daughter of a military officer of the Regiment, who passed away when she was nine years old, and at the time it was decided by the Board of Officers that she be adopted by the Regiment. An annual assessment was levied upon the members for her education and maintenance of one dollar annually, and her education was carefully supervised. She married in 1863, and on the day of her marriage, the Board of Officers presented her with the sum of $2,000 as a gift.

When Louis Comfort Tiffany was hired as the primary designer of the Veterans Club Room, he was 32 years of age, and had not yet made his famous Tiffany Lamps. Instead, he was known as a landscape painter. He hired a young Stanford White to act as consulting architect, and their commission of the Veterans Room went so well that they were then commissioned to do the adjacent Library. The Veterans Room is one of the few surviving interior spaces in the entire world created by Tiffany and other prominent artisans associated with this project.

The Library, adjacent to the Veterans Club Room

Drill Hall transformed with 122,000 gallons of water occupying 33,000 square-feet underneath two pianos for the installation Tears Become Streams Become

The 55,000 square-foot drill hall was designed to look like a great European train shed by Charles Clinton, co-architect of The Apthorp. It was originally used for marching drills. However in 1881, it was thought that perhaps the room would make a good performance space, and music festivals were hosted there. They once held a festival with 1,200 singers – long before fire regulations. Today, it is the main performance space for the Park Avenue Armory.

In 2014 Scottish conceptual artist Douglas Gordon and French pianist Helene Grimaud filled the drill with water in the performance Tears Become Streams Become.

The Drill Hall was used for broadcasting the radio play The Fall of the City by Archibald MacLeish because of its acoustic properties. The thirty-minute radio play first broadcast in 1937, featured a cast of Orson Welles and Burgess Meredith. The music was composed and directed by Bernard Hermann. This was the first American verse play written for radio and was broadcast live. To simulate a crowd, they often used extras from NYU (students), New Jersey High School students, and the boys clubs.

Lobby off the entrance of the Park Avenue Armory

In its commitment that art should be for all, the Park Avenue Armory requires one free performance by all artists. When Branagh’s Macbeth was performed, the 1,000 seats in the Drill Hall were filled with public school students. In addition, student interns work as ushers and set designers under the Arts Education program at the Armory. To date, more than 111 artists have directly interacted with students through this program. Over 1,144 workshops have been created to serve more than 20,000 students and their families.

The Lenox Hill Neighborhood House Women’s Mental Health Shelter has been welcoming eighty women over the age of 45 to the Park Avenue Armory women’s shelter since 1996. Here, the women find a hot meal and a wide range of social and health services located on the fourth floor. This program is primarily funded by the New York City Department of Homeless Services, with some support from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The Park Avenue Armory continues its renovation program, while welcoming the public to a vast array of programming. They are located at Park Avenue and 67th Street.

Next, check out NYC’s 22 remaining armories and how they’re used today. Contact the author at AFineLyne.

Subscribe to our newsletter