How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

Situated on the west side of Manhattan on the Hudson River are four piers stretching from 17th to 23rd streets known as Chelsea Piers. Long before Chelsea Piers became the recreation center it is today, it had an interesting past tied to ships like the infamous RMS Lusitania and the RMS Titanic, and with both World Wars, making that area of Chelsea deeply engrained into the transportation history of New York City for over 100 years. In light of the upcoming anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, here are the top 10 secrets of Chelsea Piers.

“New Chelsea Piers on the Hudson,” 1912 . Photo from Library of Congress.

“New Chelsea Piers on the Hudson,” 1912 . Photo from Library of Congress.

Opened in 1910, Chelsea Piers became one of the city’s busiest ports for those famous large ocean liners. Most notably, passenger ships traveling along the White Star and Cunard Lines back and forth between Europe and New York docked here. The piers could hold five ocean liners at once, showing onlookers a total of twenty steaming smokestacks that stood on the ships.

The ships transported the rich and famous from Europe, but thousands of immigrants also came in with them. The ships would dock at Chelsea and then those entering the United States would be ferried from these piers to Ellis Island. If you’re familiar with the movie Titanic, you already have a pretty clear image of what the lavish life on board these ships looked like.

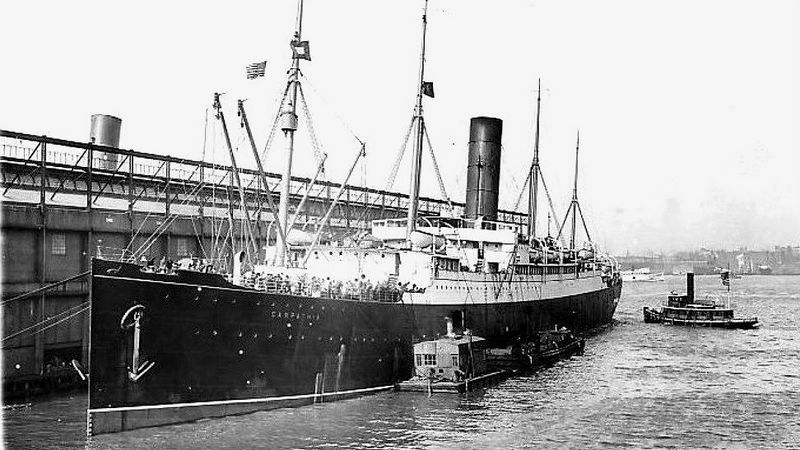

The Carpathia bringing back survivors to Pier 54 in 1912. Image via Wikimedia Commons in Public Domain

The sinking of the Titanic on April 14, 1912 is still remembered today as one of history’s most infamous accidents. Although the ship never made it to the United States, upon leaving Southampton on April 10th on her maiden voyage, the “unsinkable” ship, bound for New York, was scheduled to dock on Pier 59 on April 16th.

After striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic, the Titanic sunk, bringing down with it 1,525 passengers, including prominent New Yorkers like Benjamin Guggenheim and John Jacob Astor IV. The remaining 675 passengers were rescued by the Carpathia, a Cunard liner. On April 20th, the Carpathia brought the Titanic’s lifeboats to Chelsea Pier’s Pier 59.

For more, check out Titanic: The Millionaire’s Ship and Its Connection to the South Street Seaport

Photo from Library of Congress

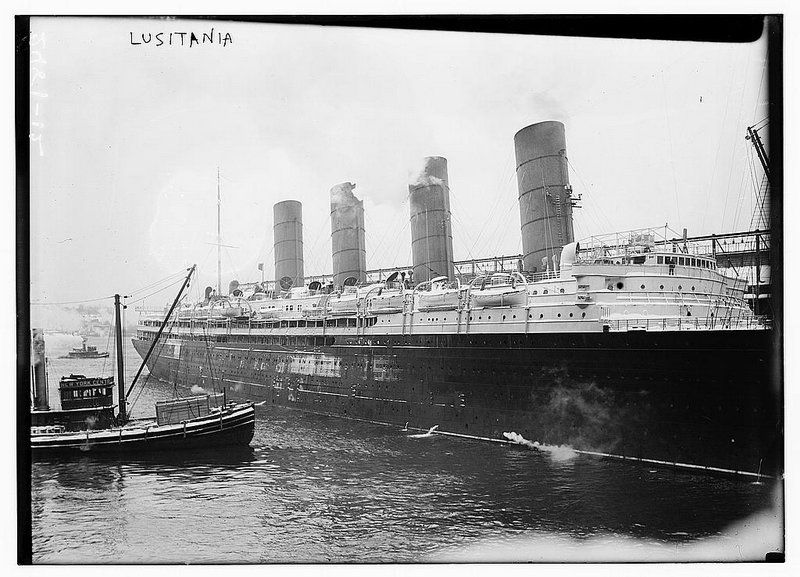

A few years later, Chelsea Piers became tied to another tragic event, the sinking of the Lusitania. On May 1, 1915, the Lusitania departed New York from Chelsea Piers for Liverpool, England. Despite warnings from the Germans that they would sink any ships attempting to pass through to England, Captain William Turner decided to sail anyway, confident that the Germans would not be able to keep up with the ship’s incredible speed.

More than half way into the transatlantic journey, as the Lusitania approached the south of Ireland, three British merchant vessels were sunk by German U-boats. Even after receiving alerts of active U-boats in the area, Captain Turner slowed down presumably because of a fog warning. On top of basically ignoring all kinds of directives to avoid U-boats, the ship was ultimately doomed.

On May 7th, a German U-boat fired one torpedo. The ship sunk in 18 minutes, killing 1,195 of the 1,959 on board, including 123 Americans. The sinking of the Lusitania sparked outrage in the United States and was the climactic event that prompted the U.S. to enter World War I.

Former 13th Avenue being converted into a new part of Hudson River Park

On April 12, 1837, New York City’s 13th Avenue was created after New York State Legislature passed an act to “establish a permanent exterior street in the city of New-York along the easterly shore of the North, or Hudson’s River.” The avenue was to extend from West 11th Street all the way up to 135th Street in Harlem and constructed out of excavated land from the north of the city in upper Manhattan.

But even though the avenue was established through a state act, construction never really got anywhere. At its peak, it extended from W 11th Street up to only W 25th Street, never making it further than Chelsea. By 1874, it was reported by the New York Times that the lower regions of the avenue were a “dreary waste” home mostly to lumber yards, saloons, and city dumps.

At the turn of the 20th century, New York City began to focus more on improving the conditions of its ports instead of worrying about getting a whole other avenue built. Today, only a single block remains of 13th Ave, known as Gansevoort Peninsula where there’s a building belonging to the city’s sanitation department. It is the city’s shortest avenue.

Remnants of 13th Ave (street designation in red added in an edit by Untapped Cities). Image via Google Maps

Want to know more? Check out our Daily What?! 13th Avenue is the Shortest Numbered Avenue in Manhattan

Photo via Library of Congress

Photo via Library of Congress

Towards the end of the 19th century, the city’s focus shifted on creating new piers on the west side of Manhattan. The architectural firm put in charge of designing Chelsea Piers were non other than Warren & Wetmore, the very firm that was designing Grand Central Terminal at the same time.

The firm’s design of Chelsea Piers saw the removal of the random collection of run-down waterfront structures. In their place would stand a row of grand buildings decorated with pink granite facades. Officially opened in 1910, it took 3o years of talks and eight years of construction to get there.

The 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin were one of the most controversial, nicknamed “The Nazi Olympics,” since Adolf Hitler was the Chancellor of then Nazi-ruled Germany. Despite the attempts to boycott the games, the United States and other democratic countries decided to participate. That summer a new name was etched into sport history with American Jesse Owens winning four gold medals in track.

The U.S. Olympic Team left for Munich on the S.S. Manhattan, which departed from Pier 60. Upon their return, the team docked in Chelsea, where huge crowds of people gathered to see Jesse Owens.

See the team arrive back in New York in the video below:

Crowded ship bringing back American soldiers to New York Harbor after V-Day in 1945. Image by U.S. Navy via New-York Historical Society

During World War I, Chelsea Piers was a popular port from which soldiers and other military personnel would embark. When the Great Depression hit, transatlantic travel drastically decreased and use of Chelsea Piers’ ports became very infrequent—at least for passenger travel.

During World War II, the port picked up traffic once again as a major point of embarkment for American soldiers going to Europe. But after the war, passenger service never fully recovered and Chelsea Piers was never able to gain back its importance as a passenger port for ocean liners.

Beginning in the early 1950s, commercial flights from America to Europe became more frequent. The rise in flights ultimately ended Chelsea Piers’ career as an important transatlantic port for ocean liners, with nearly all trips stopping in 1958. Instead of closing, Chelsea remained open, but was transformed into a cargo terminal.

It remained a cargo port until 1967, when the Grace and United States lines, two of the port’s biggest tenants, relocated to New Jersey, effectively ending Chelsea’s run as a cargo port, too. From then until the 1990s, the pier fell into decay, going basically unused, and was even scheduled for demolition. But later efforts would revitalize the area.

In 1976, there were some movements to convert Chelsea Piers into a waterfront recreation center, but those plans were never fully realized until much later, as there wasn’t much enthusiasm among citizens. A demolition plan was scheduled in the ’80s, though that never happened either. Left to decay for years, the piers became crumbling structures of rust and wood, degraded to nothing but warehouses, a city Tow Pound (Pier 60), sanitation truck repair shop (Pier 59), and a U.S. Customs impound station (Pier 62).

In May 1992, after a six month research process, the New York State Department of Transportation obtained the rights to renovate the area and construct the Chelsea Piers Sports and Entertainment Complex. Beginning in 1995, the area opened in stages with a golf club, the sky rink, and field house. After a $100 million renovation, the once neglected Chelsea Piers was transformed once again into a busy port.

The old Pier 57, still standing today, has yet to be renovated for any future plans though it has been the site of a pop-ups market. But this building is significant because of its engineering by designer Emil Praeger, which put it on both the State and National Registers of Historic Places.

Once the piers were redeveloped, many became used for different kinds of sports. But several famous TV and film studios are located at the piers. Silver Screen Studios, located at Pier 62, is Manhattan’s largest center for television and film production. Some former tenants were shows like Law & Order, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, Spin City, and Ready, Set … Cook. Movies filmed here include You’ve Got Mail, The Preacher’s Wife, Six Degrees of Separation, and Everyone Says I Love You.

Pier 59 Studios is also another premier photography and multimedia center with studios used for a range of purposes, including hosting live events and renting out project space for organizations.

Next, check out Vintage Photos: Chelsea Piers as a Neo-Classical Shipping Terminal and the Remnants of Chelsea’s Pier 54, A Cunard-White Star Line Pier With A Tragic History

Subscribe to our newsletter