Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Since the 1990s, the increased amount of construction work in New York City has allowed previously unseen markers of the city’s colonial past to be unearthed. We’ve brought you highlights from the NYC Archaeological Repository and 5 notable archaeological sites unearthed in Manhattan. But beginning in 2005, the Museum of the City of New York‘s archaeological team started excavating for the South Ferry Terminal Project. Those excavations have yielded thousands of artifacts along with structural remains of the colonial New York’s Battery Wall and Whitehall Slip.

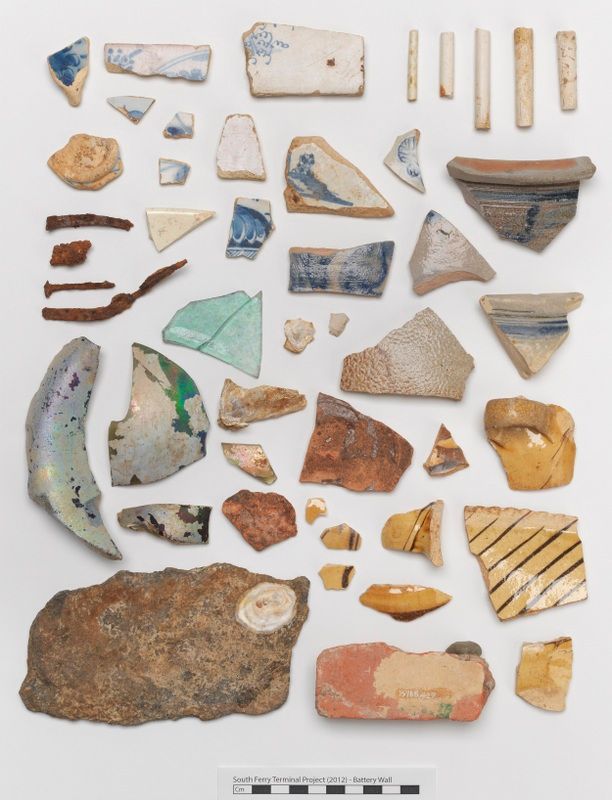

Finds from the collection. Image from Museum of the City of New York

In 2005, the City of New York was renovating the South Ferry subway station, and since it’s known that early occupations of the city were at the southern tip of Manhattan, it was no surprise when archaeologists were called to the scene. Today, in 2016, the excavation has long since been done, but the Museum of the City of New York’s archaeological team, in collaboration with the Landmarks Preservation Commission are now digitizing the 2005 finds from the South Ferry Terminal.

This digitization project will be launched on a online public database upon completion where the images of these finds will be available to view in full, vivid color. Along with the South Ferry finds, City Museum and Landmarks are digitizing other finds as well with the hopes of increasing public access to the New York City Archaeological Repository, where finds from all over city from various excavations are stored.

The pictures you will see here are just a few of the fabulous finds from the South Ferry Terminal Collection put online by the City Museum on their MCNY Blog: New York Stories. The official, final report of the excavation was published in April 2012, giving a detailed description of the history of the project, methods used, statement of research questions, historic context of the site, field results, artifact analysis, ending with conclusions and recommendations. The whopping 750-page report was prepared for the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA).

The Battery Wall pictured above was found underneath today’s Battery Park. Built as a fortification on the Southwestern tip of Manhattan around the 1740s and 1750s, it was a defense against any enemies but also against the rough waves slamming into New York Harbor. In the late 18th century, the wall became buried under landfill, and was subsequently lost when colonial fortifications were demolished and Battery Park was built in the early 19th century. Multiple sections of the wall were discovered during the excavation, and at one site remained at 40-foot long segment.

Section of the “Plan of the City of New York” by Bernard Ratzer in 1766-67, with Battery Park in the bottom left of the island. Image via Library of Congress

Along with the wall, many other small artifacts were discovered such as a medal bestowed to Admiral Boscawen by King George III commemorating his role as a naval commander in the British capture of Fort Louisbourg. The wing bone the Passenger Pigeon, a now extinct species of bird. A glass bottle seal belonging to Benjamin Fletcher who served as the British colonial governor of New York from 1692 to 1697, and the base of sugar mold that was a very important tool in refining sugar before the creation of the refineries in the 19th century.

Front and back of a copy of an Admiral Edward Boscawen Louisbourg Medal 1758. Image from Museum of the City of New York.

Passenger Pigeon wing bone. Image from Museum of the City of New York.

Base of a sugar mold. Image from Museum of the City of New York.

This last object may not look like much, but it serves as a grim reminder of New York’s participation in the slave market. Archaeologists speculate that the “X” or “+” scratched onto the pebble seen below was a West African cosmological symbol. Many similar artifacts like this have been found throughout the East Coast and are believed to have been deposited into river beds after ritual ceremonies. It may just be a small pebble, but if the African Burial Ground isn’t enough proof, than this just further evidence of the urban slavery of the early 19th century of those who helped build the New York we know today.

Scratched pebble. Image from Museum of the City of New York.

Though the excavation in 2005 shed a lot of light on colonial New York, what’s important now is that this collection is being digitized and that it will be searchable by the public. This will allow further research into this time period by opening up the discussion to outside of the New York area. Digitizing has become increasingly useful and important in the field of archaeology because it gives researchers, students, and the general public access to quick information for whatever they may need it for. Needless to say, but what the MCNY and Landmarks Commission are now doing is very exciting.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of NYC’s Former Slave Market on Wall Street.

Subscribe to our newsletter