Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The New-York Historical Society Museum & Library has been a part of New York City for 212 years, collecting and preserving the history of the city and nation. It holds an incredible amount of documents and art that make the building a treasure trove of information. Holding so much history lends itself to having some secrets of its own. Why is New-York hyphenated? How old is really? What does Santa Claus have to do with it? Those and more are answered with our top 10 secrets of the Historical Society.

Founded in 1804, the New-York Historical Society is the oldest museum in New York City, predating the founding of the Metropolitan Museum of Art by nearly 70 years. Today, the building houses more than 1.6 million works of art and documents. The museum’s mission is to explore the political, cultural, and social history of New York City, the state, and even the nation. With small exhibits, a comprehensive online database, and ground-breaking exhibits like Slavery In New York that promote “the discussion of issues surrounding the making and meaning of history.”

Exhibitions and education programs are supported by one of the country’s greatest collections of historical artifacts, a full range of American art, and many historical documents.

Back in 1804, New York was typically written with a hyphen between the two words. Used in newspapers and books, the practice even extended to the names of other states like New-Jersey and New-Hampshire. Usage of the hyphen decreased in the mid 1800s, with the New York Times being one of the last holdouts still put it in the masthead of the paper until the 1890s. The Historical Society kept it given that that was the common spelling of the city during the Society’s founding, and also reinforced its commitment to preserving New York City history.

The hyphen generally went unnoticed, until 1945 when an angry city council men noticed the hyphen on a subway ad. According to a New York World-Telegram reporter, Chief Magistrate Henry H. Curran told President of City Council Newbold Morris “This thing -this hyphen- is like a gremlin which sneaks around in the dark… You should call a special meeting of City Council immediately and have a surgical operation on it! We won’t be hyphenated by anyone!”

Even after a silly exclamation, the Council, did in fact, tried to pass a law barring the use of the hyphen in New-York. Librarians and curators of the Historical Society held their ground and explained it has been there since its founding. One curator even remarked that they couldn’t change it now, it was after all chiseled into stone on the building. The World-Telegram report was mocked by many citizens since it was World War II. A group of musicians even wrote a song called “The Hyphen-Song” which they performed at a City Council meeting.

Today, the hyphen remains proudly a part of the Historical Society’s name, and is even part of the Society’s summer softball team name “The Hyphens.” Who new a little line could cause so much hullabaloo.

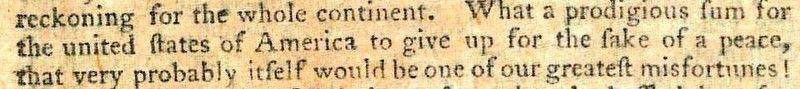

Above is what’s previously been though as the earliest use of “United States of America.” Image via N-YHS

The first usage of the phrase “United States of America” as the name of our country has long been disputed. Yes, it is in the Declaration of Independence, but there is some earlier evidence. The above image is thought to have been the first, appearing in the Virginia Gazette on April 6, 1776, found by Byron DeLear of the Christian Science Monitor. But then he bettered his own findings when he brought the Historical Society’s attention to a January 2, 1776 report by Stephen Moylan to George Washington. Moylan, an acting secretary to General Washington said “I should like vastly to go with full and ample powers from the United States of America to Spain.”

It may not seem so impressive now, but this was seven whole months and a week before the country declared independence from Britain. If Moylan came up with it, that is unclear. But there’s some idea that maybe his superior, George Washington had used it before, thus prompting Moylan to use it in a letter. We typically attribute the name to Thomas Jefferson, John Dickinson, Thomas Paine, and Elbridge Gerry. But now Washington and Moylan can be added to the list of credit.

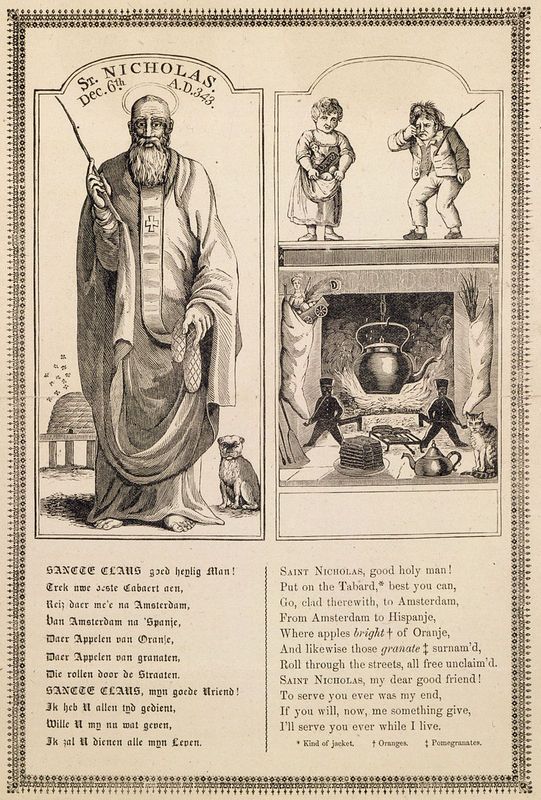

Alexander Anderson’s commissioned drawing of the American image of Santa Claus. Image via Wikipedia

John Pintard, the founder of the New-York Historical Society was a busy man who established lasting institutions and customs in New York and in the country. Besides serving on the executive board of many organizations like the New York Chamber of Commerce, Pintard was instrumental in advocating for the free public school system in New York today. He was also heavily involved in the plans for completing the Erie Canal, stayed in New York during the second cholera pandemic, and a deeply religious man.

That last part may not sound like a great accomplishment next to all the other things he’s done, but his religious involvement gave our country one of its most famous people: Santa Claus. St. Nicholas, the saint Santa is modeled after, has long been celebrated in Europe (and by the Dutch in New Amsterdam) around Christmas on a holiday called St. Nicholas Day. Pintard promoted St. Nicholas as the patron saint of both the Historical Society and New York. In January 1809, Washington Irving joined the Society and wrote a satirical fiction story called Knickerbocker’s History of New York where our American image of jolly, old Saint Nick the gift giving, chimney climber was created.

Starting on December 6, 1810, the Historical Society began celebrated St. Nicholas Day ever year. The same year, Pintard commissioned artists Alexander Anderson to create the American image of St. Nick helping to popularize Santa Claus. So, ladies and gentlemen, the American Santa Claus had its roots in New York.

In October 2014, the oldest, unopened time capsule in New York City from 1914 was opened at the New-York Historical Society. This bronze case was closed 100 years ago by the Lower Wall Street Business Men’s Association. On May 23, 1914, a group of men in Revolutionary War garb marched from Fraunces Tavern to 91 Wall Street where the former Merchants’ Coffee House used to be (often thought of as the birth place of the American Revolution).

Meeting the revolutionary men, former Columbia University president Seth Low sealed a bronze time chest with a silver hammer and entrusted it to the President of the Historical Society, set to be opened in 1974. But because of it was uncatalogued, the time capsule got lost. It wasn’t until the 1990s when curators were cataloging artifacts that they found it.

The Society had designated October 8th the anniversary of the Dutch colonization of the New York area, and so decided to open the time capsule on October 8, 2014 to mark the 400th anniversary of the settlement. The contents were fairly mundane, as they are in most time capsules, with everyday objects that show what life was like during that time. Included in the 1914 capsule were things like a copy of letter written at the Merchants’ Coffee House, telegram to the time capsule curator from the governor, a photograph of John Jay’s daughter, the May 15, 1914 edition of the New York Herald, and copies of the World Newspaper.

To see more about the big unveiling, check out our coverage of it and what was inside.

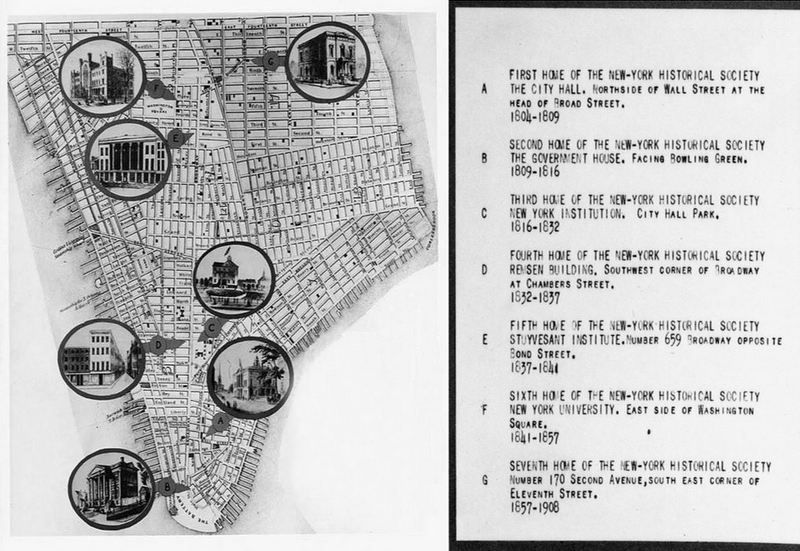

The 7 previous N-YHS locations. Image via N-YHS

The New-York Historical Society has only been in its current building on Central Park West since 1908. Before that it moved around quite a lot, changing locations seven times before construction began for 170 Central Park West in 1902. It’s first home was at City Hall in Lower Manhattan until 1809. Next, it moved to Bowling Green to the Government House (no longer standing), which was originally constructed as the house of the President of the United States when New York was the temporary capital. The map above gives a nice visual of where the museum and library moved. The second to last location, or the seventh was along Second Avenue, on the southeast corner of 11th street, pictured below.

The New-York Historical Society moved uptown to the Upper West Side because of much needed space for the growing collection. Construction of 170 Central Park West broke ground the same year the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its doors on Fifth Avenue in 1902.

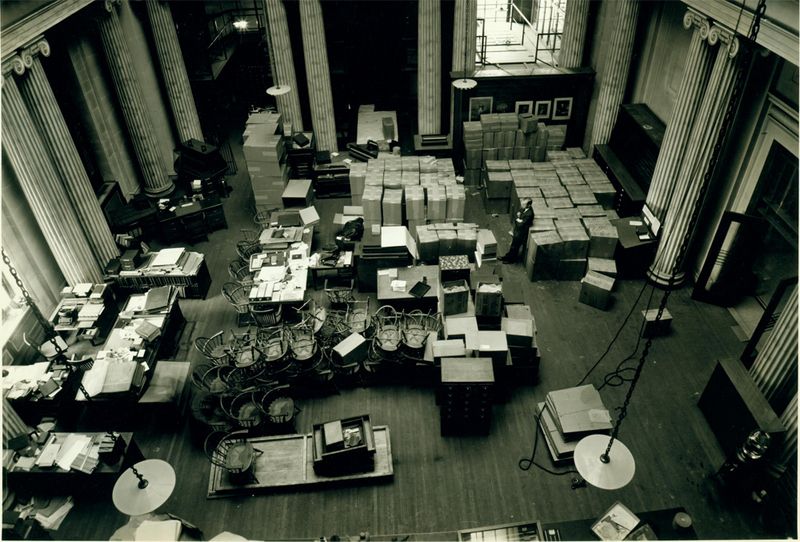

N-YHS Archives. Image via N-YHS

The Klingenstein Library in the New-York Historical Society is one of the oldest and distinguished in the United States, with more than 3 million books, pamphlets, maps, newspapers, broadsides, music sheets manuscripts, prints, photographs, and architectural drawings. Among these documents is one of the best collections of 18th century newspapers in the country, and a vast collection of Civil War materials, including Ulysses S. Grant‘s terms of surrender to Robert E. Lee.

Another distinguished title of this library is that it is one of only sixteen libraries in the country qualified to be a member of the Independent Research Libraries Association. It continues to receive important research materials, and holds the archives to many organizations. In 2013, the library was a finalist for the National Medal for Museum and Library Service.

“Le Tricorne” tapestry on the left wall

Pablo Picasso’s “Le Tricorne” used to hang in the lobby of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building. The 19-by-20 foot tapestry hung against a wall that was very damaged, so the owners of the Seagram wanted to take town the tapestry down to repair the wall. There was some conflict over the removal of the Picasso work. Having been hung there for 55 years, it, too, was falling apart, and removal could destroy the work.

There was a rumor going around that the owner just really didn’t like the Picasso, and were looking for a way to get rid of it. Whatever the decision, the tapestry was successfully moved and installed in the New-York Historical Society building, on display since March 29, 2015. It was the first Picasso work to enter the New-York Historical’s collection. It is currently being shown with other N-YHS objects, many from the European tradition that give background on Picasso’s work and the traditions he rebelled against. See the video of its installation here.

Image via Wikimedia Commons in public domain

Among the impressive collection in the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library, it has all 435 surviving preparatory watercolors for John James Audubon‘s impressive work of Birds of America, a book that shows all the species of birds in North America. The works at the Historical Society are the works that Audubon created as prep work for the final copies that would go into his first editions. Learn more about the books’ contents at John James Audubon’s Birds of America organization where they have detailed information and a digitized collection of the books.

While the historical society on Central Park West is about New York the city and state, then what is its relation to the Brooklyn Historical Society? When the New-York Historical Society had formed, it was mainly concerning the history of the island of Manhattan since that’s where most of the city’s earliest history happened. It soon moved on to have collections that would develop more discourse on state wide history and national history.

The Brooklyn Historical Society (BHS) was founded as the Long Island Historical Society in 1863 when civic pride in Brooklyn was starting to kick into gear. In an effort to retain some of the rural history of Brooklyn, BHS was created. The N-YHS takes in very broad history and as an organization trying to create a comprehensive history of the city, information can get lost when too much is being collected. So the BHS was created to tackle more specific local histories that doesn’t necessarily have to be a part of the national dialogue as intensely as the N-YHS.

Next, check out Vintage Photos of the 12 Oldest Museums in NYC and take a look Inside the Hispanic Society of America in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter