1. No One Really Knows the Origin of the Word Gowanus

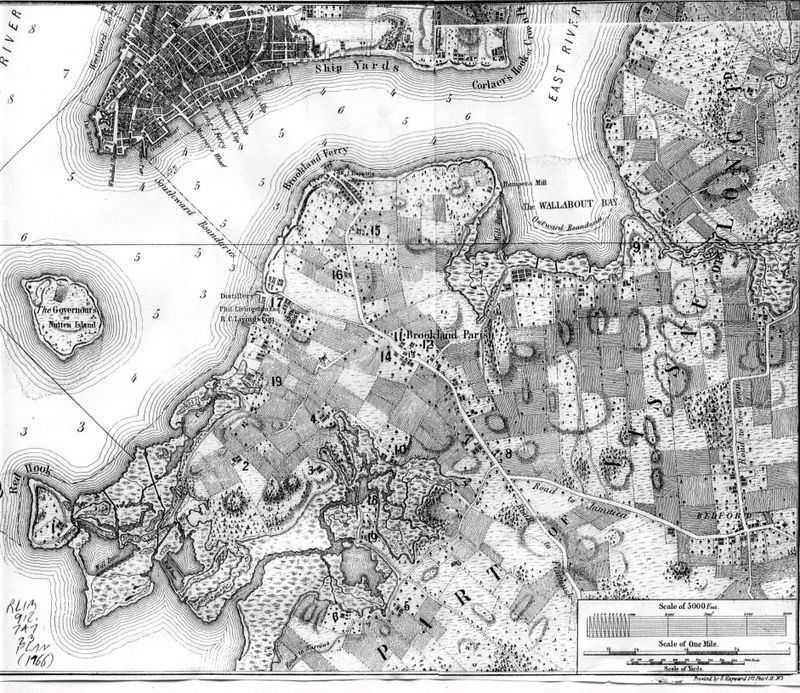

Map of Brooklyn in 1766, showing what was then the Gowanus Creek surrounded by marshland. Number 18 and 19 are the location of two important mills along the Gowanus Creek. In public domain from Wikimedia Commons. Also located in New York Public Library.

As recounted in Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal, the 19th century historian Martha Bockée Flint wrote, “No Long Island name is more puzzling and elusive than Gowanus.” The most prevalent origin story is linked to a Lenape chief named “Gouwane,” though no documents from that time period reference him. A linguistic theory points to the word Gowanisque (or Cowanisque) which comes from the word Ka-hwe-nes-ka, meaning “at on the long island.” Similarly, the word Gä-wa-nase-geh is said to be the Oneida word for “long island.” Still many others disagree with the Indian etymological connection but Alexiou writes that regardless, the word ‘Gowanus’ is clearly older than ‘New York’ and ‘New Amsterdam,’ and certainly much older than the name ‘Brooklyn.'”

2. The Gowanus Canal Once Had “Sandbars” of Human Waste

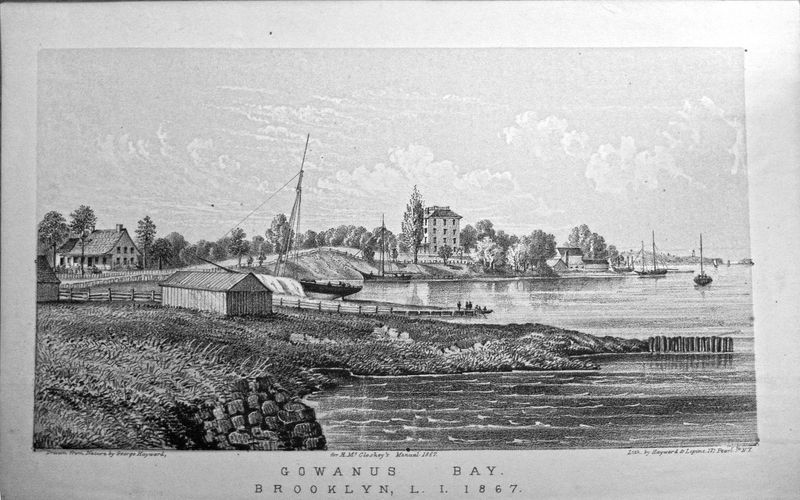

Courtesy of NYU Press, from Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal

There may be luxury condos going up next to the Gowanus Canal, but it doesn’t change the fact that the body of water is a combined sewer outflow (CSO) for the city – thanks to an engineering plan deemed both state of the art back in 1857. In fact, there are 11 of these outfalls that deliver sewage into the canal when rainwater is high, “dumping almost four hundred million gallons of wastewater into the canal every year,” writes Joseph Alexiou in Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal.

1861 was the first recorded legal complaint regarding the smell of the Gowanus Canal and its adverse health effects. Historically, the sewers used to get so backed up that by the 1870s that “sandbars of human waste” appeared along the canal, both a public health issue and navigation problem. In 1908, a test determined that the Gowanus Canal contained 625,000 bacteria per cubic meter (legally swimmable water in New York State can contain maximum 24 bacteria per cubic meter). Today, pollution continues to be an issue with high levels of nitrates, presence of toxins like mercury, lead and and PCBs, and bacteria. It even tested positive for typhoid, cholera and gonorrhea in the recent past.

3. Many Whales Have Appeared in the Gowanus Canal

A celebrity for a day, Sludgie, a baby minke whale was spotted at the mouth of the Gowanus Canal in April 2007. According to Joseph Alexiou in Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal, New Yorkers seemed to want something to root for following a large storm and the mass shootings at Virginia Tech. But by the time Sludie arrived to the canal, it already had suffered numerous cuts on her head from bulkheads along the Gowanus Bay. Due to the storm, the level of sewage was beyond inhospitable for the baby whale which had been separated from its mother. She beached onto rocks near the beginning of the canal and died a day after it was first spotted.

Alexiou writes that although the connection between water quality and Sludgie’s death was never confirmed, “her sudden, startling appearance had focused attention on the murky and mysterious waters of the Gowanus once again.”

But even before this, whales had been spotted in the Gowanus Canal on numerous occasions, with official police recordings dating back to at least 1922. In addition to whales, there have been dolphins, sharks, and a seal – but few of the the stories usually end well.

4. The Idea for a Canal Originated as Early as the 1600s

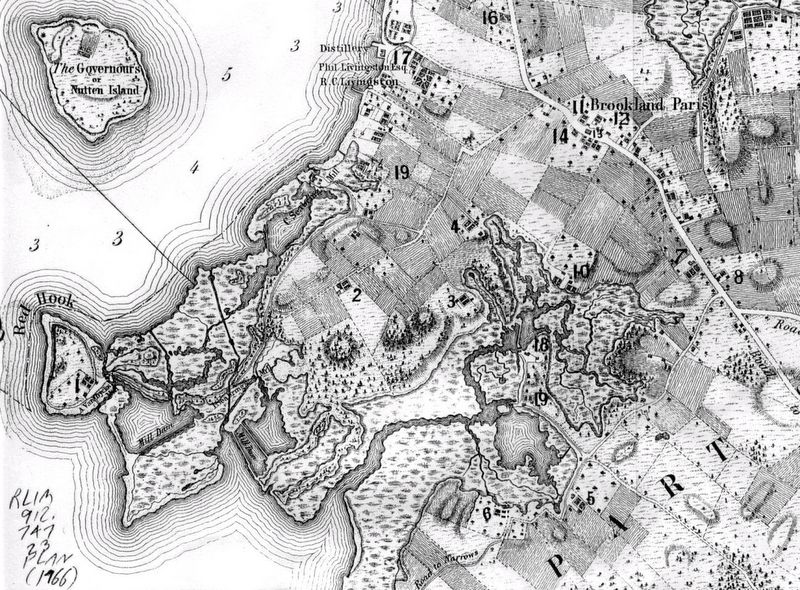

Brouwer’s Mill on Gowanus Creek, number 18 on the map. In public domain from Wikimedia Commons. Also located in New York Public Library.

This story of Brouwer’s Mill (also known as Freeke’s Mill) is not only important for the designation of being the oldest mill on Gowanus. Mr. Adam Brouwer, who built the mill, was the first to suggest the creation of a canal to avoid the dangerous waters around Red Hook. The mill, built before 1661, was located next to a hand-dug millpond, and would have been located in the middle of the present day canal. Over the the next century and more, the canal would repeatedly be widened to accommodate the increasing demands of industry and trade.

Get your tickets for this Thursday’s talk by Joseph Alexiou, author of Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal at the Museum of the City of New York here.

5. Gowanus Oysters Used to Be Over a Foot Long

A first person account by a Dutch missionary named Jasper Danckaerts, recounted in the book Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal, describes Gowanus oysters in 1679 as “large and full, some of them not less than a foot long, and they grow sometimes ten, twelve and sixteen together, and are then like a piece of rock.” Danckaerts loved them so much, he called them “the best in the country,” and later found them to be better than those he had in Maryland and Virginia. Not all the oysters were eaten fresh however – some were pickled and sold throughout the colonies, while the shells were burned and used as fertilizer.

6. The Gowanus Creek Was the Unsung Hero of the Battle of Brooklyn

Lord Stirling, who fought on the American side, ordered New Yorkers to assist in the defense of the city “every other day,” with the help of their slaves. This directive was officially passed by the New York Provincial Congress, who then required those in Kings County (Brooklyn) to follow suit. An earthen wall built in Brooklyn started at the head of Gowanus Creek and stretched to Wallabout Bay (where the Brooklyn Navy Yard is today). As Alexiou writes, “with several redoubts, it provided an inner layer of defense for Brooklyn,” with a Fort Box protecting Gowanus.

Despite this defense, the Americans would lose the Battle of Brooklyn, of which much was fought on the edges of Gowanus Creek. The famous Patriot retreat involved crossing the Gowanus Creek. Many of the troops drowned or were shot in the crossing.

Still Alexiou writes, “It is fair to call [the Gowanus Creek] an unsung hero of the Battle of Brooklyn—twice critical to the escape of Washington’s army. More than Battle Pass, honored by several plaques tucked away in Prospect Park, the Gowanus waters bore witness to that bloody day in history, as have generations of Brooklynites since.”

7. American Soldiers Would Bathe Naked in the Gowanus Canal

Kayakers in the Gowanus Canal

As noted in an orderly book from a American colonel, Gowanus inhabitants complained in 1776 of naked soldiers, swimming in the Gowanus Creek “in the open View of the Women.” They didn’t bother to reclothe en route to their tents, “with a design to insult & wound the Modesty of Female Decency.” The soldiers in Brooklyn, which in 1776 were the most concentrated of the Continental Army, were also known to raid the oyster beds of the locals. Even today, New Yorkers kayak the Gowanus Canal as well as attempt swims.

9. In the 1800s, the Gowanus Area Was a Slum

The book Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal notes the many efforts of private citizens to transform the Gowanus Creek and environs. In 1856, akin to a modern day slum tour, New York journalists were taken to see the slums of Gowanus in horse-drawn carriages. The neighborhoods teemed with European, particularly Irish, immigrants working within walking distance at the Red Hook docks. In rains, raw sewage would flood the shanties of the slums.

Get your tickets for this Thursday’s talk by Joseph Alexiou, author of Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal at the Museum of the City of New York here.

10. The Lost Sport of Ice Baseball Was Popularized Near the Gowanus Canal

The nascent sport of baseball was particularly popular in Gowanus. The Old Stone House, scene of the Revolutionary War battle less than a century before, became a clubhouse in 1855. Games were played in the fields around the house, unless they flooded – which was fairly common given the original marshland nature of the area. When the temporary ponds froze over, Brooklynites would ice skate on them, with entertainment brought in – crowds reached upwards of 10,000 at these gatherings. By 1861, the ice skating craze got combined with the baseball craze to create ice baseball. The game on February 4, 1861 between the Atlantics and the Charter Oaks was witnessed by 12,000 people.

As Alexiou describes in the book:

The rules to ice baseball were essentially the same as for regular baseball but with certain concessions: there were only five innings and only ten players allowed on the field; the ball was painted bright red for greater visibility and was somewhat softer than a normal baseball. The bases were scratched into the ice, and players could overshoot them and still be safe, like with first base in a regular game. With different seasonal physics to work with, the best skaters soon grabbed the title of most valuable ice baseball players.

11. The Famed Wall Remnant on 3rd Avenue is Not From the Dodgers’ Washington Stadium

The walls above in Gowanus along 3rd Avenue if often cited as a remnant of Washington Park, where the Brooklyn Dodgers played before moving to Ebbets Field in 1913. However, it is actually from the park built for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops in 1914.

12. One of the Earliest Known Concrete Buildings in New York City is on the Gowanus

Before the Whole Foods in Gowanus was built, a handsome building stood alone, left over from the concrete industry that came before. The Coignet building was the showcase for a new material, now known as concrete that took the building industry by storm, starting with the 1867 Exposition Universelle de Paris. Industrialists in America started the Coignet Stone Company and created the Coignet building as both office and a “flagship prototype,” writes Alexiou in Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal.

What’s just as interesting is that this imitation sandstone has been incorporated not only in residential and commercial buildings in New York City, but also in its most renown landmarks. Alexiou sites the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cleft Ridge Span in Prospect Park and Saint Patrick’s Cathedral as some of the most notable.

Next, read about the many secrets of Prospect Park.