How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

The location of New York City’s potter’s fields (a term which the New York Times explains comes from the Bible) follows the path of the city’s development from the early days of the country. Potters fields were located in what was considered far enough from what were then the boundaries of the current settlement. Many of our most notable parks were once potters fields, including Washington Square Park, Union Square Park, Madison Square Park, Bryant Park, and more.

Hart Island was purchased by New York City in 1868, used prior as a prison camp for Confederate soldiers during the Civil War, and burials began in 1869.

Today, Hart Island is home to over a million buried bodies, making it is the largest tax-funded cemetery in the United States. About 1500 burials take place per year.

Also in New York City is the largest of all cemeteries in the United States, Cavalry Cemetery in Queens with over 3 million buried.

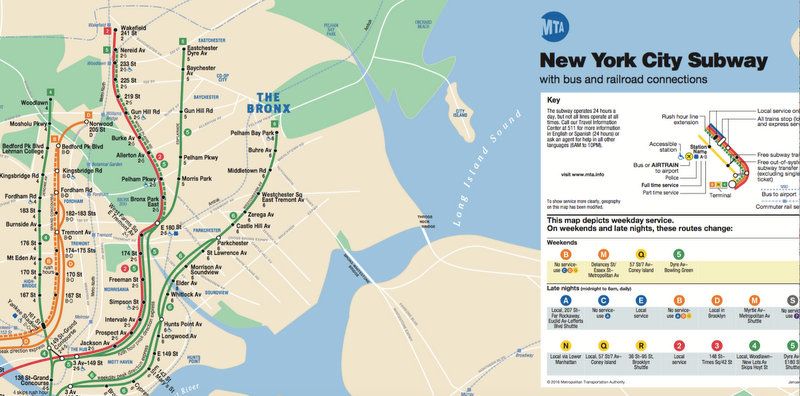

Hart Island is just to the east of City Island, but is not drawn on the MTA maps

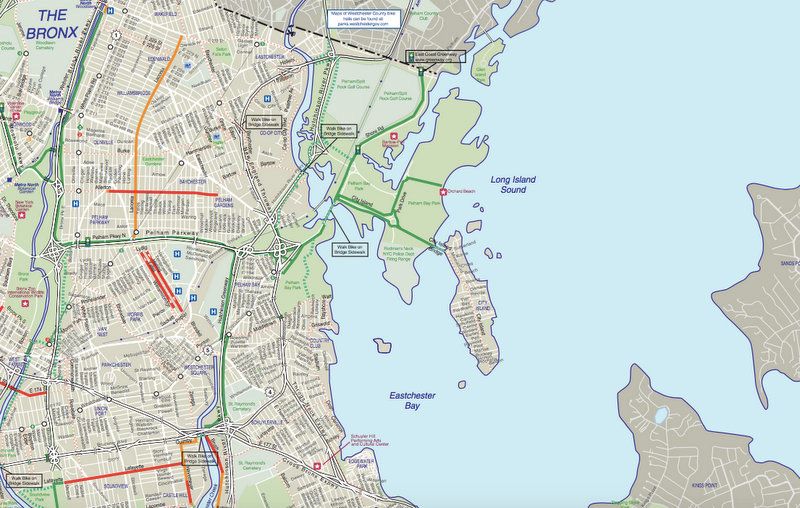

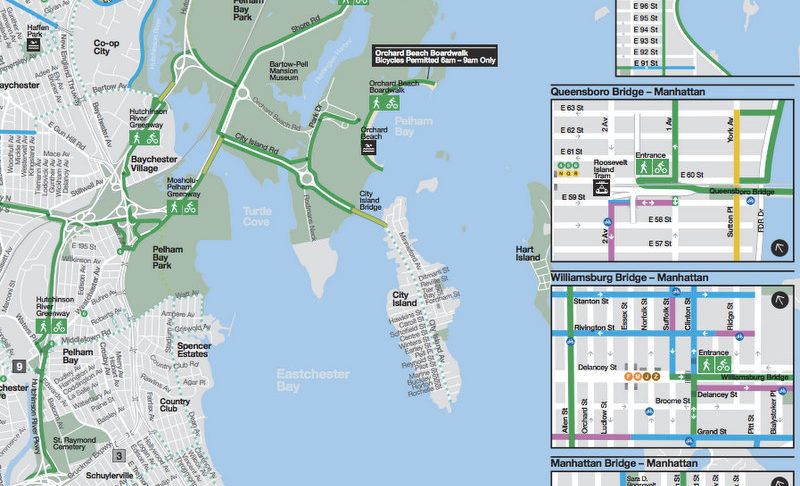

The MTA subway and bus maps are known to leave out or exaggerate details for clarity, and Hart Island is certainly one of those details. Unlike Rikers Island, which is alternatively labeled and unlabeled depending on the version of the map, Hart Island is not even drawn on the map. Similarly, Hart Island did not appear as any kind of land mass in the Department of Transportation Bicycle Maps until 2012, where it was labeled “Hart Island Potter’s Field.” But starting in 2015, half of Hart Island was covered over by zoomed in maps of other neighborhoods.

2011 NYC DOT Bike Map, missing Hart Island

2013 and 2014 NYC DOT Bike Maps, showing Hart Island

2015 and 2016 NYC DOT Bike Maps, Hart Island is cut off

Even historically, the 1906 IRT subway map, which was much more detailed than later maps, cuts off just after City Island (although the map is fun, because you’ll see the shoreline of the Bronx prior to the infill that became Orchard Beach.

Two times a week, the newly dead are brought by ferry to a dock on the eastern side of Hart Island. Prior to the 2021 transfer of management to the Parks Department, this ferry also brought inmates from Rikers Island. The inmates dug the trenches and buried the bodies stacked in threes, three feet under the ground. In recent times, Rikers Island prisoners were paid for this work, which used to be a daily activity in the 1800s. The New York Times has a great map showing the location of burials on the island since 1869, derived from maps at the The Hart Island Project.

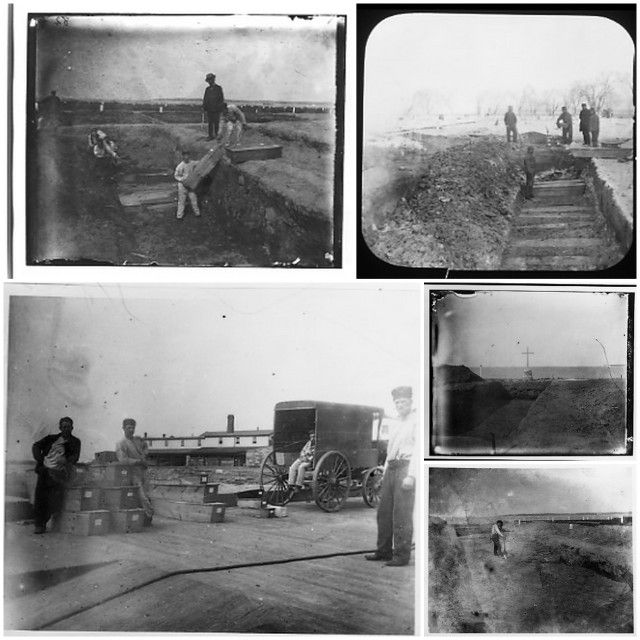

Hart Island photographs by Jacob Riis

According to Melinda Hunt, who runs the Hart Island Project, “When [Jacob Riis] first acquired a camera in the 1890s, the first place that he went was Potter’s Field.” He describes Hart Island in the book, How The Other Half Lives:

One free excursion awaits young and old whom bitter poverty has denied the poor privilege of the choice of the home in death they were denied in life, the ride up the Sound to the Potter’s Field, charitably styled the City Cemetery. But even there they do not escape their fate. In the common trench of the Poor Burying Ground they lie packed three stories deep, shoulder to shoulder, crowded in death as they were in life, to “save space;” for even on that desert island the ground is not for the exclusive possession of those who cannot afford to pay for it.

On the 100th Anniversary of Riis’ first photograph, Melinda Hunt and photographer Joel Sternfeld photographed the island using the same 8×10 format Riis used. These photos were published in the book Hart Island: Discovery of an Unknown Territory.

Like many of the city’s other islands, Hart Island has served as the home for many of New York City’s unwanted activities. There have been military barracks for the U.S. Navy during World War II, a narcotics rehabilitation center, a quarantine zone for yellow fever, a prison, women’s insane asylum, a tuberculosis hospital, a Cold War Nike missile base, and a training camp. Many of these buildings still stand abandoned, including an abandoned chapel, the hospital buildings, offices for the Department of Corrections full of papers and more.

Even for those with relatives buried in Hart Island, visiting is known to be a challenge. According to Melinda Hunt of The Hart Island Project, New York City is the only municipality that demands people to provide a death certificate before visiting the public cemetery. Visits are allowed only once a month on Thursdays and by request, and until 2015, visits were limited to a small gazebo near the ferry dock. Starting in 2015, gravesite visits were also allowed once a month – 2016 dates are all on either Saturday or Sunday. As a direct result of the activism of the Hart Island Project, the Department of Corrections updated the administrative code for Hart Island operations, with burial records and a visitation policy published online.

Bobby Driscoll, the Disney child actor, is one of the “notable” people buried in Hart Island. Driscoll was the voice of Peter Pan in the animated film and starred in Disney’s Song of the South. He died unknown, thought to be homeless, so was taken here. The grave of the first child to die of AIDS is also on Hart Island.

Melinda Hunt from the Hart Island Project has previously spoken about one grave different than the rest – that of the first child to die of AIDS in New York City.

Buried deep in the wooded area, however, there was one marker with an unusual number, “SC-B1, 1985.” Upon inquiry, we found that the marker belonged to a solitary grave of the first child victim of AIDS to be buried on Hart Island. Extra precautions were taken to bury the child in a separate and deeper grave. This AIDS grave seemed like a ‘tomb to an unknown child. It came to represent all children who were yet to die of AIDS as well as child victims of earlier epidemics.

16 other AIDS victims were buried in the 1980s on the southern half of the island, under 14 feet of soil as an added precaution.

A 2016 Google Earth View shows the current trenches

Melinda Hunt of the Hart Island Project has been fighting to make Hart Island visible and accessible –not only for those with loved ones buried on the island but also for public record. The Hart Island project website records the stories of those on the island buried since 1980 and allows anybody to upload information. Records of many earlier burials were lost in fire.

As the New York Times article shows, about 300 to 600 of 1,500 buried on Hart Island a year are used as medical cadavers, a practice which continues today. The article states, “An opt-out provision in the law would seem to exempt the bodies of people who indicate that they do not want to be dissected or embalmed. But few are aware of it, and it may be unenforceable.” And sadly, reports the New York Times, record keeping of these types of body loans is “sloppy; documents show some bodies signed out and never signed back in.” And, cadavers can be checked out for long periods of time – sometimes for years.

People end up in Hart Island for a myriad of reasons – their own destitution, the destitution of next of kin, a lack of known relatives, abuses in the guardianship system, lost personal records indicating a person’s burial choice, among others. In some cases, people have been lost in the hospital and nursing home system, despite attempts by relatives to locate them.

But family members who are successfully located can be disinterred, and the New York Times article ends with two slightly more uplifting stories. Meanwhile, the Hart Island project continues to record stories of those buried here and make them more visible to the public.

Next, check out the secrets of Roosevelt Island and delve into New York City’s other islands.

Subscribe to our newsletter