Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Bowery Boys Greg and Tom. Image courtesy of Benjamin Stone Photography

Grey Young and Tom Meyers are “The Bowery Boys,” the voices behind the popular podcast series that provides thousands of listeners with fascinating stories of New York City history. Today marks the release of the Bowery Boys’ new book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York which gives readers the entire story of Manhattan from top to bottom, neighborhood to neighborhood.

For a sneak peak into this colorful book, Untapped Cities is excited to share an excerpt from Chapter 4. Below you will find the history surrounding Hanover Square and the Great Fire of 1835, along with points of interest in Manhattan’s East Financial District.

The book! Find The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon. Photo by Michelle Young/Untapped Cities.

“Stone Street, Pearl Street, and the other curvy, narrow lanes that surround Hanover Square may say more about New York’s history than any other area in the city. They’re like the rings of an old tree.

Today’s streets mimic the original lanes used by the residents of Dutch New Amsterdam, who were themselves following old Lenape Indian paths established long before. Stone Street retains only a portion of its original length (the lobby of the out-of-place 85 Broad Street tower helpfully brings the two sections of the street back together). Pearl Street was the original coastline.

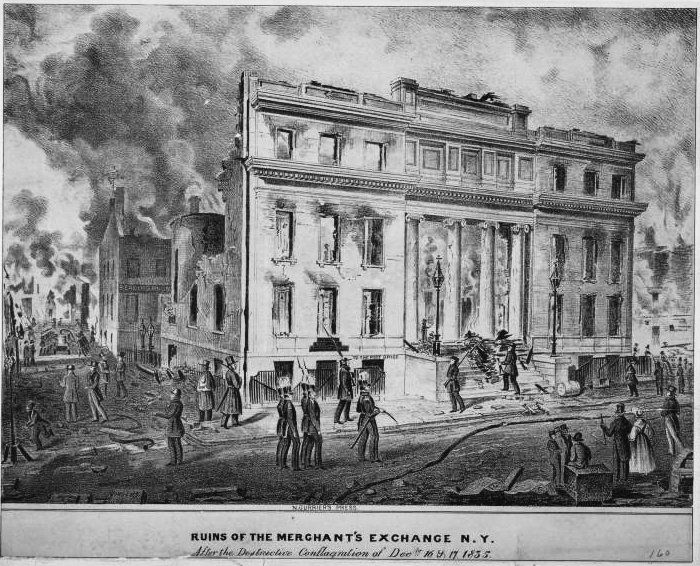

The Merchant’s Exchange ablaze during the Great Fire of 1835. Image via the NYPL

These street names originate from a variety of eras. Pearl Street was a British corruption of the Dutch “Peral-Straat,” named for the pearly oysters that bedazzled the riverbed. William Street is named for the Dutch landowner Willem (or Wilhelmus) Beekman; he was such a stand-up guy that you’ll see his name all over the city.

And Beaver Street might have the most important name of all. As New York was initially a settlement for fur traders, city fathers named a street for the mammal that traders killed the most. Beaver “wool,” as they called it, was exported from the new colony to Europe in the seventeenth century, where it was all the rage.

Hanover Square sounds rather British, and it is, named in the 1730s for the English dynastic House of Hanover, of which King George III was a member. His was the equestrian statue ripped down in Bowling Green in 1776 (see Chapter 2). He was also almost certainly mentally ill, but that’s for another book.

So you get the picture: Both the physical streets and their names go way back. But with the exception of Fraunces Tavern (which is today mostly a reconstruction anyway), no buildings stand here that are more than 200 years old. Where’d they all go? Almost everything, from Wall Street all the way down to the Battery, was destroyed in a single terrible incident: the Great Fire of 1835.

Stone Street charms today, but it too was engulfed by flames during the 1835 blaze. Photo by Greg Young

By the 1830s the area below Wall Street had become the commercial heart of the island. Hanover Square, its name restored following the understandably anti-British period that swept through New York following the Revolutionary War, was by now surrounded by newspaper offices and book publishers. The streets bustled all day long with residents and merchants (many of whom lived above their shops). The side streets just off the square were lined with dry goods wholesalers and warehouses, each packed with merchandise and supplies that were being bought, traded, and stored—fabrics, housewares, lumber—all of it fueling the city’s growth, and all of it quite flammable.

On the windy and exceptionally cold evening of December 16, 1835, a fire broke out at a dry goods wholesaler at the corner of today’s Pearl Street and Exchange Place. As the streets were so narrow, flames handily leaped from building to building. Volunteer firemen from around the city raced to the spot, the area of the fire now quickly growing, to try to contain the blaze, but they found themselves direly outmatched. As they frantically pumped water from the East River, the frigid night air froze the water to ice right inside their leather hoses. Their pumps jammed. When, finally, they could get the water to flow again, the frozen spray blew back upon the men, covering their coats in ice.

Soon every bell and alarm in town was sounded, and anxious (and curious) New Yorkers raced down to witness the fire. Afraid that the fire would soon engulf their shops, business owners began tossing their inventory out into the street. Some hauled their property off to seemingly safer buildings outside the path of the blaze, only to see those buildings too succumb as the fire, spreading unpredictably, changed course and engulfed them.

“[T]he fierce dragon of flame soon overtook them in these places of fancied security and devoured the edifices with their precious contents,” wrote historian Benson John Lossing in 1884. “When the shutters, warped with heat, were unfastened and flew open, the interior of these great stores appeared like huge glowing furnaces. The copper on their roofs were melted and fell like drops of burning sweat to the pavement.”

For a time, Hanover Square was giving shelter to valuable goods, but these too were caught aflame by flying embers. Saltpeter began exploding a block away. For several hours, the fire raged on, spreading uncontrollably. By midnight New York’s entire East Side was in flames. The fierce night wind blew embers, like fiery bombs, across the East River, catching the rooftops of Brooklyn houses on fire.

Amazingly, those raging bitter winds kept the inferno to the south side of Wall Street. But soon the Tontine Coffee House, by 1835 one of the city’s most important financial centers, was endangered, its shingles now flecked in fire. One wealthy bystander, Oliver Hull, announced he would give $100 to the firemen’s fund if rescuers could save the building. His offer was accepted— the unpaid volunteers who made up New York’s fire department were able to save the Tontine from the blaze.

Firefighters had no other choice—they had to use dynamite on their own city in order to save it. Only by blowing up the buildings in the blaze’s path were they able to stop its terrible progress.

By the time the last flame was extinguished, New York had lost more than 700 buildings, leaving a sizable portion of the city (which, at this time, only extended up to about 14th Street) in smoldering ashes. The city had suffered a financial and emotional wallop, and countless businesses simply vanished or went bankrupt. Incredibly, not a single human life was lost in the disaster.

“That portion of the city which has been destroyed contained more of talent, respectability, generosity, industry, enterprise, and all the qualities that ennoble and dignify our race, than the same space, perhaps in any other city in the world,” wrote the New-York Mirror two weeks later. The city quickly rebuilt over the so- called burnt district with a patriotic zeal.

Most of the buildings that today line this portion of Pearl Street, Stone Street, and South William Street were constructed in the years immediately following the fire. Several have experienced radical redesigns, but most retain their original form: three- to four-story Greek Revival buildings, the most popular architectural style of the postfire period. For decades, commercial concerns here sold everything from crockery and umbrellas to an exotic variety of imports. Today’s Stone Street is where you go for a pint (or three), perhaps a meal of fish and chips, and a side order of forgotten history.

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

Fraunces Tavern is one of the most important historical buildings in New York City, the site of meetings during the Revolutionary War and the place of George Washington’s emotional farewell speech to his Continental Army officers after America had secured its freedom in 1783. In the two brief years that New York served as the new nation’s capital, the offices of the Departments of War and Foreign Affairs were located right here in the Tavern. At some point, both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr worked here. Can’t you just see them with big stacks of parchment, squeezing past each other in the hallway?

Much of the colonial exterior you see today is a fanciful reconstruction. But Fraunces has always endured as a persistent embodiment of American virtue, even surviving destruction twice by terrorizing forces—200 years apart.

In the opening chords of the Revolutionary War, Samuel Fraunces was an open supporter of America’s fight against the British. During the summer of 1775, when student instigators from nearby King’s College—including the aforementioned Hamilton—stole a cannon from the Battery and fired at a British naval ship, the war vessel returned the compliment, sending a cannonball crashing through Fraunces’s roof.

A more deadly attack occurred exactly 200 years later and from a truly mysterious source. The tavern was busy with a lunchtime Wall Street crowd on January 24, 1975, when a bomb tore through the dining room, killing four men and nearly blowing out the side of the restaurant. The bomb was planted by FALN (Armed Forces of Puerto Rican National Liberation), a rogue terrorist group that bombed several locations in New York in the 1970s. No one was ever arrested for the attack.

Inside the dining room along the Broad Street side hangs a large mural depicting New York in 1717. It’s scarred by a large crack, a lasting reminder of the FALN attack. (54 Pearl Street)

The office tower at 85 Broad Street might seem ordinary and uninteresting—the former home of Goldman Sachs, natch—but it happens to shield an important piece of New York City’s history in its shadow.

On its northeast corner on Pearl Street, you’ll find cream-colored bricks in the sidewalk that demark the location of New York’s first City Hall building. It was also, no surprise, a tavern.

In 1641, Director-General William Kieft had a costly stone structure built at what is today Coenties Slip and Pearl Street and called it City Tavern. Why “Tavern”? Back then, taverns served more purposes than simply dispensing booze. They served as inns, meeting halls, social networking places, and sometimes even offices. It makes sense then that when the city was incorporated in 1653, City Tavern morphed into what would be New Amsterdam’s very first city hall (Stadt Huys, or city house).

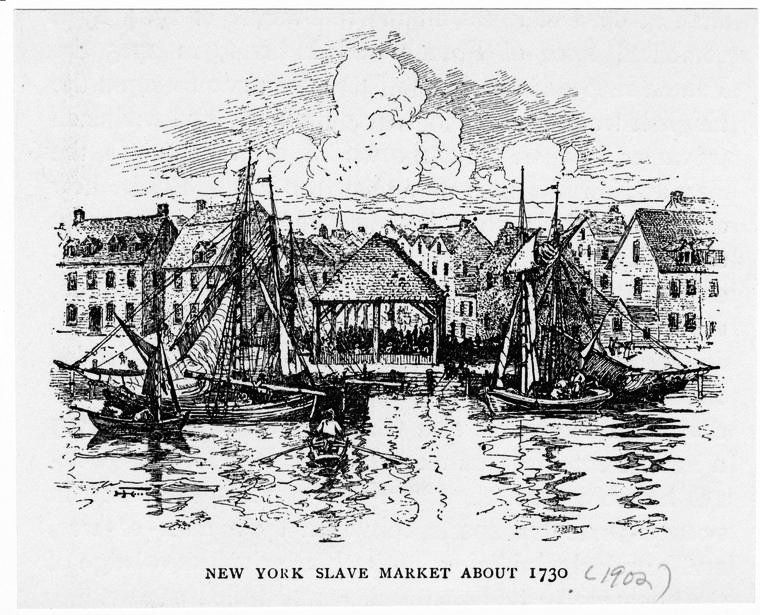

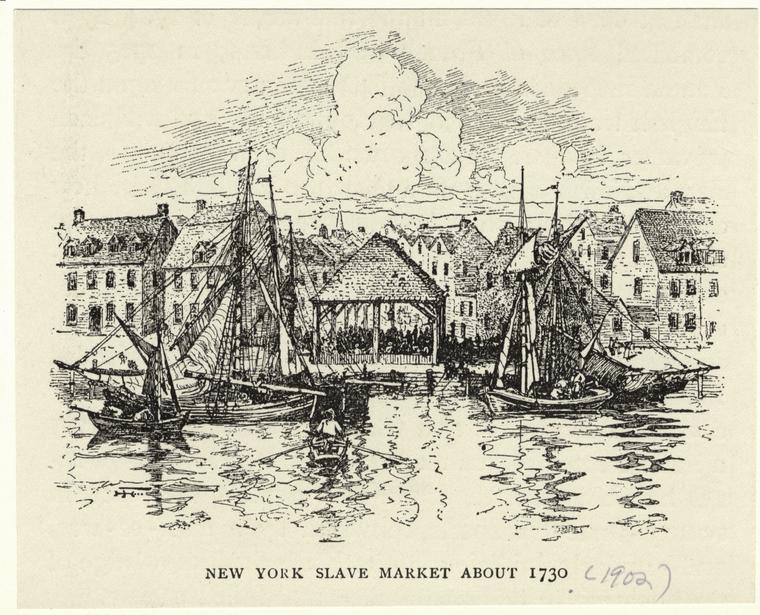

A 1902 illustration depicting how the New York slave market might have looked along the waterfront in 1730. Image via NYPL

When the British took over control of the colony in 1664, the building kept its place of importance. Underscoring its position was the building to its south, erected in 1670 as a tavern and owned by the governor of New York, Colonel Francis Lovelace.

Lovelace’s Tavern was conceived as a second-tier administration building and seemed to offer the same services as the larger building. (It’s sometimes referred to as the “King’s House.”) In fact, the tavern connected right into the municipal chambers, making it effectively an annex of City Hall. Lovelace’s Tavern was a popular place, its halls crowded until the wee hours with revelers, drinking wine and smoking their pipes.

Lovelace’s Tavern burned down in 1706 and the land was reallotted for development in the growing mercantile district. But you can still see remnants underfoot, here in the shadow of 85 Broad Street. (85 Broad Street)

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

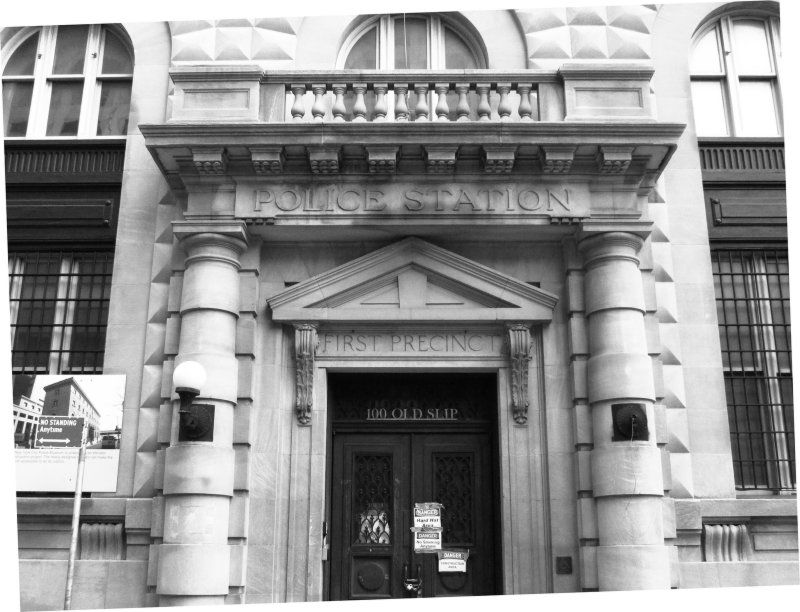

Imagine all the cop shows and movies you’ve seen that are based in New York. If they shot on location, they probably took place in some of the city’s old Gilded Age police precinct buildings, which popped up optimistically all over town about 100 years ago during a period of massive police reforms. This stalwart at 100 Old Slip, built in 1909, was specifically designed to police the waterfront district. In fact, the street’s name references the original water inlet that once ran along here. Today the building is home to the New York City Police Museum, although damages suffered during Hurricane Sandy have kept it shuttered for years. (100 Old Slip)

The police station at 100 Old Slip must have seen its share of seafaring scallywags. Photo by Greg Young

Not only was the legendary seventeenth-century privateer (okay, fine, “pirate”) William Kidd (aka Captain Kidd) a New Yorker, he was a wealthy one at that. His home at 119 Pearl Street, at the southern tip of Hanover Square, was situated close to the old wall for which Wall Street was named. It was waterfront property, back before all that landfill got in the way, the better to gaze out over the harbor’s many islands where maybe he buried a treasure or two. (See Chapter 1.)

The Kidds’ lavish home—with “104 ounces of silverware,”(4) a healthy wine cellar, and the biggest Turkish carpet in the city—allowed him to pay for a pew at the newly built Trinity Church in 1698. The captain even donated equipment to aid in the church’s construction. No Kidding. (119 Pearl Street)

(4) From Edward Robb Ellis’s The Epic of New York City.

The street is named Mill Lane, stuck like an appendage between South William and Stone Streets, a half block south of Hanover Square. It’s approximately thirty feet long, or the length of five or six Wall Street bankers, laid end to end. (Mill Lane)

Mill Lane: Home to the city’s first Jewish community during the Dutch years. Photo by Greg Young

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

Photo by Greg Young

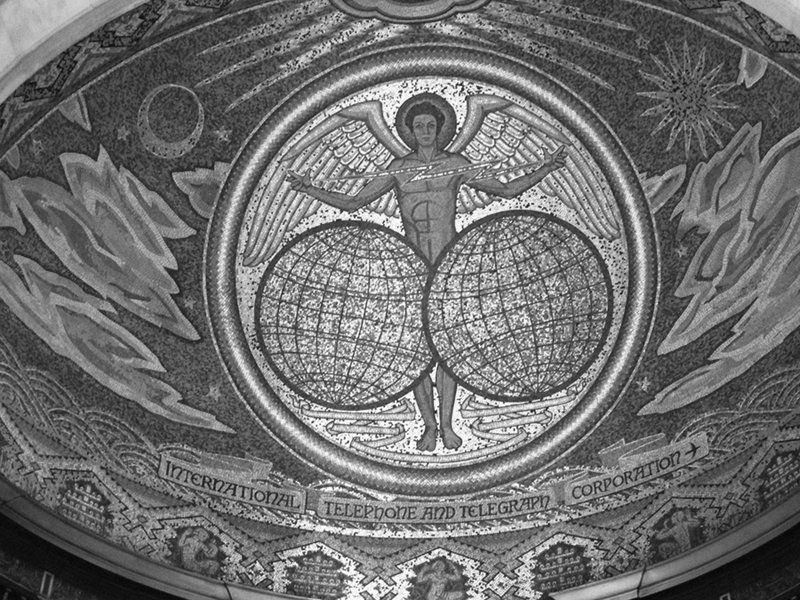

The tile mosaic above the entrance at the International Telephone and Telegraph Building at 75 Broad Street, constructed in 1928. A brawny nude angel directs electricity into the dual worlds of telecommunication. So subtle! (75 Broad Street)

Delmonico’s was New York’s first great restaurant, introducing in 1827 the fineries of French cuisine to a city accustomed to gorging on oysters out of a slop bucket. For more than a century their various locations throughout the city became the feasting place of cigar-chomping power brokers and celebrated authors salivating over Lobster Newburg or a flaming Baked Alaska (both of which were first cooked up in Delmonico’s kitchens).

Delmonico’s still dishes it up in a swanky setting here on South William Street. Photo by Greg Young

Delmonico’s original restaurant at 23 William Street was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1835. They quickly rebuilt, and when an enlarged restaurant opened in 1891 here at 2 South William Street, the architect incorporated elements from the original location: a set of columns purportedly plucked from the ruins of Pompeii (back in the days when one could just pluck columns from ancient ruins). Had one of the original Delmonico brothers, John or Peter, visited Greece instead of Italy, maybe we’d see a piece of the Parthenon hoisted over the door. (2 South William Street)

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

Sketch of New York slave market in 1730. Image via Digital Collections/New York Public Library.

Many secrets lie locked within the street plan of lower Manhattan. One of the most disturbing is the city’s relation to slavery, which existed in the city from its earliest days until the early nineteenth century. Many of the structures mentioned in this chapter—including the wall of Wall Street itself—were constructed by slave labor. One of the most notorious landmarks of the slave trade sat here, at the corner of Wall and Water Streets (once the shoreline, back in British New York). The Meal Market was established in 1711 not only for the buying and selling of raw products like grains, but also for the purchase and leasing of “negroes and Indian slaves.”(5) (Wall and Pearl Streets)

(5) Notes of the City Council, December 13, 1711.

Float around the Financial District and admire the impressive architecture—and notice that everything seems to be always sitting in the shadows. Because there are so few wide-open public spaces down here in Lower Manhattan, building designers and architects often made the details on these facades extra bold in order to make them “pop” along the dark canyons. Many of these details recall a time when sea transportation and shipping were critical to the financial success of New York City.

The towers at the corner of Wall and Pearl Streets wear the brooches of ocean travel. The Seamen’s Bank for Savings was formed in 1829 as a sailors’ bank. Onto the exterior of its former headquarters at 74 Wall Street, built in 1926, you will find fantastic carvings of sharks, pelicans, sea monsters, and other living accouterments of the sea.

Across the street, over at 67 Wall Street, more bold mythological drama awaits: the whimsical faces of gods and goddesses, including Athena’s owl. (67 and 74 Wall Street)

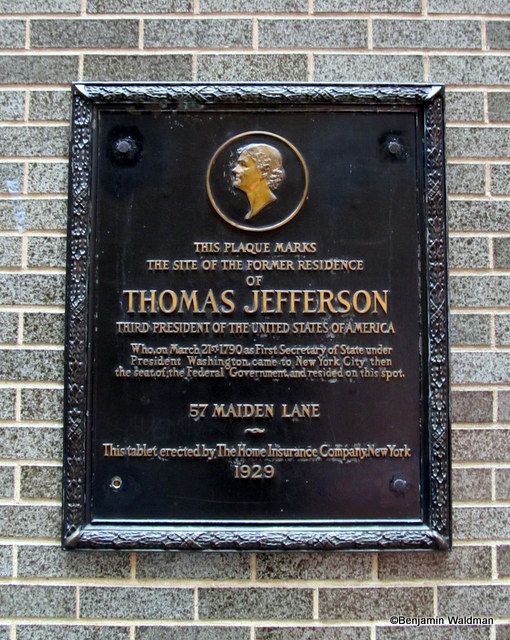

We visited Washington’s former residence in Chapter 2. Now get this: 1) Thomas Jefferson’s former home was at 57 Maiden Lane (there’s a plaque in the enchantingly named “Home Insurance Plaza” approximating its location); 2) Alexander Hamilton’s former home, 57 (then 58) Wall Street, was three blocks away from Jefferson’s; 3) Aaron Burr’s former home, 3 Wall Street, was just two blocks away from Hamilton’s. And as if we need to remind you—Burr would later mortally wound Hamilton in a duel in 1804. (57 Maiden Lane)

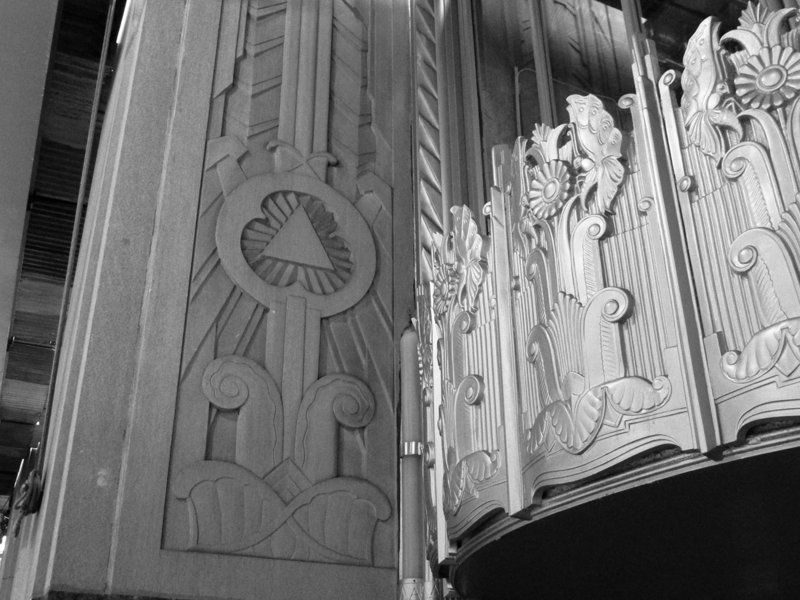

At first glance, 70 Pine Street does not appear to be filled with intrigue. This glamorous 1932 art deco skyscraper, once called (rather blandly) the American International Building, has delightful silvery ornamentation that makes it feel like the Chrysler Building’s fancy-pants downtown sister. But hang on, because things get really “reflective” in the entranceways.

Lobby interior of 70 Pine

The building features a fourteen-foot miniature representation of itself inside the center pillar of the east portal. And inside that mini-me? Another, even tinier version. And this continues, building reflected in building, into the realm of subatomic particles. (Okay, we exaggerate a bit. But it gets seriously small.) Creepy things continue around the doorways, where an unusual pyramidal motif will leave you with more unanswered questions.

Are the Freemasons behind this? Is there a spooky message to decipher? Does this have to do with Mary Magdalene? Alas, no. The building was originally commissioned by Henry L. Doherty as a temple to his Cities Service Company, a utility company. Their logo was a pyramid. Today we know a greatly expanded Cities Service Company by another name: Citgo. Their logo? A pyramid. (Mic drop.) (70 Pine Street)

Mystery of the pyramids: Intriguing iconography adorns this skyscraper on Pine Street. Photo by Greg Young

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

Washington looks somewhat askance at the New York Stock Exchange (built across the street in 1903). Photo by Greg Young

Federal Hall National Memorial, currently administered by the National Park Service, has always been a popular landmark with tourists, thanks to its position on one of the most photographed intersections in New York. Who can resist that noble statue of George Washington silently meditating on the financial juggernaut of the New York Stock Exchange? As he took his presidential oath on April 30, 1789, Washington looked down this very street, Broad Street, packed with residents witnessing the birth of their new nation.

He did not, however, take the oath in the building that stands there today. The original structure was built in 1699 by the British, who used materials from the city’s demolished defense wall—the “wall” of Wall Street—to construct it. The building became the center of most governmental functions, from city administration to the meeting place of Congress and the seat of the federal government from 1789 to 1790.

The present building, the Federal Hall National Memorial (originally the U.S. Custom House, opened in 1842), looks more like an ancient Roman temple. Throw a toga over Washington’s shoulders and you could call him Caesar. But a curious link to both the original structure and Washington’s inauguration can be found inside a dark room within the building: the Freemason’s Bible used for the swearing-in of the president. Both Washington and the man administering the oath, Robert Livingston, were loyal Masons. (Wall and Broad Streets)

The Wall Street exterior of the former J. P. Morgan Bank is covered in small cuts, traces of a terrible terrorist attack that occurred on Wall Street on September 16, 1920. That day, as the streets were filling with office workers taking their lunch breaks, an unidentified man parked a horse and carriage near the corner, about 100 feet east of Broad Street. As the Trinity Church bells rang at noon, the man dropped the reins and fled, never to be seen again. One minute later, 100 pounds of dynamite exploded inside the wagon, blasting back everything in its sphere while iron slugs shot through the air, creating a horrific scene of carnage. Thirty-eight people were killed and more than four hundred were injured in the attack, many while sitting inside at their desks.

Morgan famously refused to repair his bank building, preferring to leave the pockmarks on its side in a sign of defiance. With a little morbid imagination and some amateur sleuthing, it’s still possible to trace the trajectory of the explosion along the wall to the very spot where the poor horse and wagon stood. The culprits, rumored to be Italian anarchists, were never caught. (23 Wall Street)

The Equitable Building (120 Broadway) is a whole lotta skyscraper for such a little space. Its striking, robust form befits its original tenant, the Equitable Life Insurance Society. But many considered it a harbinger of gloom and doom when it was completed in 1915 in the Wild West days of skyscraper construction. As buildings grew taller, residents soon complained that the superstructures cast enormous, dreary shadows along the streets of Lower Manhattan. Due to the controversy surrounding buildings like the Equitable and the Woolworth Building, New York’s crucial Zoning Law of 1916 dictated that buildings be constructed with setbacks, in the “wedding cake style,” as they called it, to help contain shadows and to allow more sun to reach the sidewalks.

Lobby interior of the Woolworth Building

Compare the Equitable Building with 28 Liberty Street (formerly One Chase Manhattan Plaza), one block east, the one with the weird white-tree sculpture (called Group of Four Trees). The modern plaza exemplifies the second great zoning change in New York (passed in 1961), which made it easier for skyscrapers to ascend straight up without setbacks when open public spaces were constructed at their bases. (More on that in Chapter 18.) (Pine and Nassau Streets)

Sure, across Nassau Street from 55 Liberty Street stands the hefty Federal Reserve, an imposing Game of Thrones–like fortress literally filled with billions of the world’s lucre. Who needs it! Let us cast our eyes instead upon the mischievous carved alligators that adorn the doorway of this graceful, slender tower. Why might they be smiling?

One possible clue: It was on this very spot that the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was founded by Henry Bergh (6) in 1866.

For decades this building was the headquarters of Sinclair Oil, instigators of the Teapot Dome scandal in the 1920s that almost brought down Warren G. Harding’s presidency. Their famous mascot is a green dinosaur named Sinclair, a distant ancestor of these alligators here. (55 Liberty Street)

(6) The roots of Mr. Bergh’s other great contribution to American life can be found in Chapter 16.

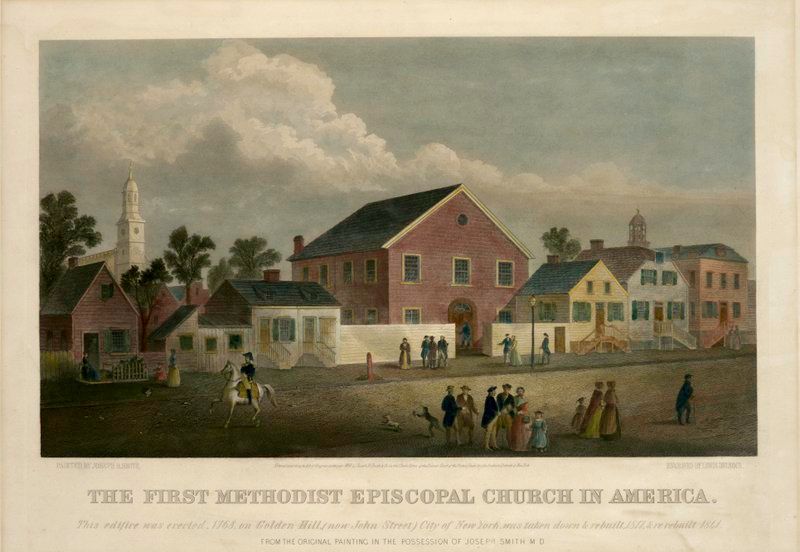

The view of Golden Hill (sometime in the 1760s) and the original John Street Church. Image via the NYPL

The view of Golden Hill (sometime in the 1760s) and the original John Street Church. Image via the NYPL

The sturdy John Street Church, which sits between two hemmed-in, open-air patios, was built in 1841, six years after the Great Fire. This was the Methodist congregation’s third church; the first was constructed on this same spot in 1768. The church’s contributions extend beyond religious history. During the Battle of Golden Hill,(7) a conflict in 1770 that took place between British forces and the revolutionary-minded Sons of Liberty, injured soldiers were taken to the first John Street Church for shelter. Today this is an almost embarrassing example of lovely old architecture being unceremoniously dwarfed by new (in this case, the Philip Johnson–designed 33 Maiden Lane, which looks like something out of a frightening science fiction novel). The berobed bust of the English theologian John Wesley (1703– 1791) in the courtyard is so not amused. (44 John Street)

(7) The Battle of Golden Hill took place approximately at the corner of John and William Streets. While a minor skirmish in the revolutionary scheme of things, several New Yorkers were injured and one was killed. Perhaps even more unbelievable: This was an actual and, yes, actually golden—with amber stalks of wheat.

To read on, the Bowery Boy’s book is available for purchase today on Amazon. Next, check out The Top 10 Secrets of NYC’s Former Slave Market on Wall Street.

Subscribe to our newsletter