Bowery Boys Greg and Tom. Image courtesy of Benjamin Stone Photography

Bowery Boys Greg and Tom. Image courtesy of Benjamin Stone Photography

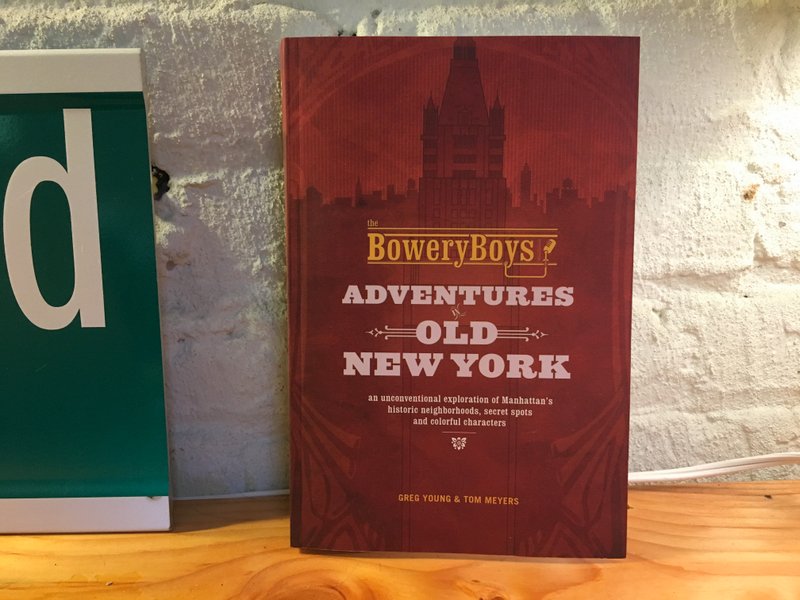

Grey Young and Tom Meyers are “The Bowery Boys,” the voices behind the popular podcast series that provides thousands of listeners with fascinating stories of New York City history. Today marks the release of the Bowery Boys’ new book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York which gives readers the entire story of Manhattan from top to bottom, neighborhood to neighborhood.

For a sneak peak into this colorful book, Untapped Cities is excited to share an excerpt from Chapter 4. Below you will find the history surrounding Hanover Square and the Great Fire of 1835, along with points of interest in Manhattan’s East Financial District.

Hanover Square and the Great Fire of 1835

The book! Find The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon. Photo by Michelle Young/Untapped Cities.

The book! Find The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon. Photo by Michelle Young/Untapped Cities.

“Stone Street, Pearl Street, and the other curvy, narrow lanes that surround Hanover Square may say more about New York’s history than any other area in the city. They’re like the rings of an old tree.

Today’s streets mimic the original lanes used by the residents of Dutch New Amsterdam, who were themselves following old Lenape Indian paths established long before. Stone Street retains only a portion of its original length (the lobby of the out-of-place 85 Broad Street tower helpfully brings the two sections of the street back together). Pearl Street was the original coastline.

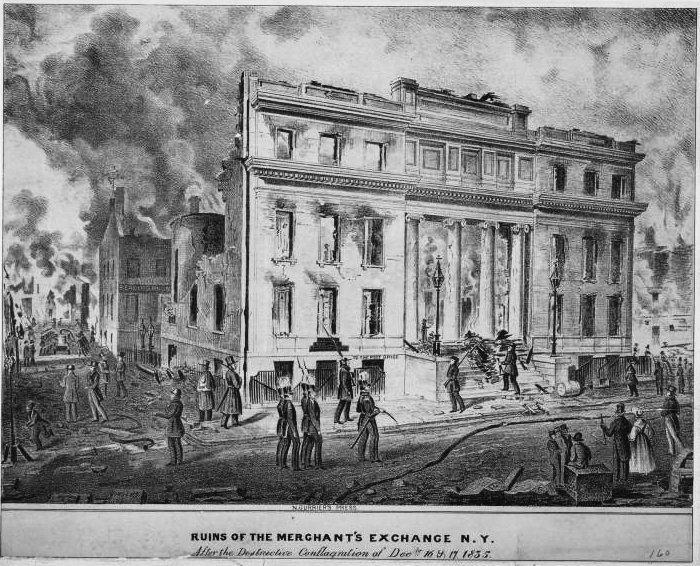

The Merchant’s Exchange ablaze during the Great Fire of 1835. Image via the NYPL

The Merchant’s Exchange ablaze during the Great Fire of 1835. Image via the NYPL

These street names originate from a variety of eras. Pearl Street was a British corruption of the Dutch “Peral-Straat,” named for the pearly oysters that bedazzled the riverbed. William Street is named for the Dutch landowner Willem (or Wilhelmus) Beekman; he was such a stand-up guy that you’ll see his name all over the city.

And Beaver Street might have the most important name of all. As New York was initially a settlement for fur traders, city fathers named a street for the mammal that traders killed the most. Beaver “wool,” as they called it, was exported from the new colony to Europe in the seventeenth century, where it was all the rage.

Hanover Square sounds rather British, and it is, named in the 1730s for the English dynastic House of Hanover, of which King George III was a member. His was the equestrian statue ripped down in Bowling Green in 1776 (see Chapter 2). He was also almost certainly mentally ill, but that’s for another book.

So you get the picture: Both the physical streets and their names go way back. But with the exception of Fraunces Tavern (which is today mostly a reconstruction anyway), no buildings stand here that are more than 200 years old. Where’d they all go? Almost everything, from Wall Street all the way down to the Battery, was destroyed in a single terrible incident: the Great Fire of 1835.

Stone Street charms today, but it too was engulfed by flames during the 1835 blaze. Photo by Greg Young

Stone Street charms today, but it too was engulfed by flames during the 1835 blaze. Photo by Greg Young

By the 1830s the area below Wall Street had become the commercial heart of the island. Hanover Square, its name restored following the understandably anti-British period that swept through New York following the Revolutionary War, was by now surrounded by newspaper offices and book publishers. The streets bustled all day long with residents and merchants (many of whom lived above their shops). The side streets just off the square were lined with dry goods wholesalers and warehouses, each packed with merchandise and supplies that were being bought, traded, and stored—fabrics, housewares, lumber—all of it fueling the city’s growth, and all of it quite flammable.

On the windy and exceptionally cold evening of December 16, 1835, a fire broke out at a dry goods wholesaler at the corner of today’s Pearl Street and Exchange Place. As the streets were so narrow, flames handily leaped from building to building. Volunteer firemen from around the city raced to the spot, the area of the fire now quickly growing, to try to contain the blaze, but they found themselves direly outmatched. As they frantically pumped water from the East River, the frigid night air froze the water to ice right inside their leather hoses. Their pumps jammed. When, finally, they could get the water to flow again, the frozen spray blew back upon the men, covering their coats in ice.

Soon every bell and alarm in town was sounded, and anxious (and curious) New Yorkers raced down to witness the fire. Afraid that the fire would soon engulf their shops, business owners began tossing their inventory out into the street. Some hauled their property off to seemingly safer buildings outside the path of the blaze, only to see those buildings too succumb as the fire, spreading unpredictably, changed course and engulfed them.

“[T]he fierce dragon of flame soon overtook them in these places of fancied security and devoured the edifices with their precious contents,” wrote historian Benson John Lossing in 1884. “When the shutters, warped with heat, were unfastened and flew open, the interior of these great stores appeared like huge glowing furnaces. The copper on their roofs were melted and fell like drops of burning sweat to the pavement.”

For a time, Hanover Square was giving shelter to valuable goods, but these too were caught aflame by flying embers. Saltpeter began exploding a block away. For several hours, the fire raged on, spreading uncontrollably. By midnight New York’s entire East Side was in flames. The fierce night wind blew embers, like fiery bombs, across the East River, catching the rooftops of Brooklyn houses on fire.

Amazingly, those raging bitter winds kept the inferno to the south side of Wall Street. But soon the Tontine Coffee House, by 1835 one of the city’s most important financial centers, was endangered, its shingles now flecked in fire. One wealthy bystander, Oliver Hull, announced he would give $100 to the firemen’s fund if rescuers could save the building. His offer was accepted— the unpaid volunteers who made up New York’s fire department were able to save the Tontine from the blaze.

Firefighters had no other choice—they had to use dynamite on their own city in order to save it. Only by blowing up the buildings in the blaze’s path were they able to stop its terrible progress.

By the time the last flame was extinguished, New York had lost more than 700 buildings, leaving a sizable portion of the city (which, at this time, only extended up to about 14th Street) in smoldering ashes. The city had suffered a financial and emotional wallop, and countless businesses simply vanished or went bankrupt. Incredibly, not a single human life was lost in the disaster.

“That portion of the city which has been destroyed contained more of talent, respectability, generosity, industry, enterprise, and all the qualities that ennoble and dignify our race, than the same space, perhaps in any other city in the world,” wrote the New-York Mirror two weeks later. The city quickly rebuilt over the so- called burnt district with a patriotic zeal.

Most of the buildings that today line this portion of Pearl Street, Stone Street, and South William Street were constructed in the years immediately following the fire. Several have experienced radical redesigns, but most retain their original form: three- to four-story Greek Revival buildings, the most popular architectural style of the postfire period. For decades, commercial concerns here sold everything from crockery and umbrellas to an exotic variety of imports. Today’s Stone Street is where you go for a pint (or three), perhaps a meal of fish and chips, and a side order of forgotten history.

Read on for more and get the book The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York on Amazon.

East Financial District: Points of Interest

1. The Attacks on Fraunces Tavern

Fraunces Tavern is one of the most important historical buildings in New York City, the site of meetings during the Revolutionary War and the place of George Washington’s emotional farewell speech to his Continental Army officers after America had secured its freedom in 1783. In the two brief years that New York served as the new nation’s capital, the offices of the Departments of War and Foreign Affairs were located right here in the Tavern. At some point, both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr worked here. Can’t you just see them with big stacks of parchment, squeezing past each other in the hallway?

Much of the colonial exterior you see today is a fanciful reconstruction. But Fraunces has always endured as a persistent embodiment of American virtue, even surviving destruction twice by terrorizing forces—200 years apart.

In the opening chords of the Revolutionary War, Samuel Fraunces was an open supporter of America’s fight against the British. During the summer of 1775, when student instigators from nearby King’s College—including the aforementioned Hamilton—stole a cannon from the Battery and fired at a British naval ship, the war vessel returned the compliment, sending a cannonball crashing through Fraunces’s roof.

A more deadly attack occurred exactly 200 years later and from a truly mysterious source. The tavern was busy with a lunchtime Wall Street crowd on January 24, 1975, when a bomb tore through the dining room, killing four men and nearly blowing out the side of the restaurant. The bomb was planted by FALN (Armed Forces of Puerto Rican National Liberation), a rogue terrorist group that bombed several locations in New York in the 1970s. No one was ever arrested for the attack.

Inside the dining room along the Broad Street side hangs a large mural depicting New York in 1717. It’s scarred by a large crack, a lasting reminder of the FALN attack. (54 Pearl Street)