The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

On July 14, 1853 America’s first “World’s Fair” opened in New York City. Called the Exhibition of the Industry of All the Nations, it was similar to the Great Exhibition in London two years prior and designed to thrust a young America onto the world stage.

The expo grounds were located on present day Bryant Park, which was then known as Reservoir Square behind Croton Reservoir (today the New York Public Library). On the premises were two impressive structures for which the exhibition will forever be remembered: New York’s Crystal Palace and the Latting Observatory. Some of the countries in attendance included Great Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Mexico, Turkey, and Haiti (or Hayti as New Yorkers spelt in 1853).

Like most large New York City projects, the expo ran both late (it was supposed to open on May 2nd) and grievously over budget. But on opening day the New York (Daily) Times reported with glee that:

“The Crystal Palace is open! The great event on which so many hopes and expectations and anxieties were clustered is at least completed. The great Temple of National Industry has unclosed its portals and displayed its treasures to the multitude.”

President Franklin Pierce was on hand to deliver an inspiring speech about a bright new age the world was entering:

“Everything around us reminds us that we live in an utilitarian age, where science, instead of being locked up for the admiration of the world has become tributary to the arts, manufactures, agriculture and all that goes to promote our domestic comforts and our universal prosperity.”

And New York’s first impressive beard and free-verser, Walt Whitman wrote a poem just for the expo aptly titled… “Song of the Exhibition.” In it he described the Crystal Palace as:

“Mightier than Egypt’s tombs, / Fairer than Grecia’s, Roma’s temples, / Prouder than Milan’s statued, spired Cathedral… / Thy great Cathedral, sacred Industry—no tomb, / A Keep for life for practical Invention.”

The massive building was designed by architects Georg Carstensen and Karl Gildemeister, both directly inspired by the design of London’s Crystal Palace. It was an iron and glass goliath built in the shape of a Greek cross and topped by a 100ft dome.

Inside, the exhibition space was divided across three floors with each floor divided into naves or wings. Exhibitors were separated by their “classes” with highly descriptive 19th Century titles like “Class 5. Machines for direct use, including “Steam, Hydraulic and Pneumatic Engines, and Railway and other Carriages,” “Class 8. Naval Architecture, Military Engineering, Ordnance, Armor and Accoutrements,” or the area I would be found in— “Class 3. Substances used as Food.” Feel free to peruse the entire Exhibition directory. May I suggest stopping off at Class 3, Division A to sample Superior pine-apple cheese or Brussels health mustard?

Image from New York Public Library

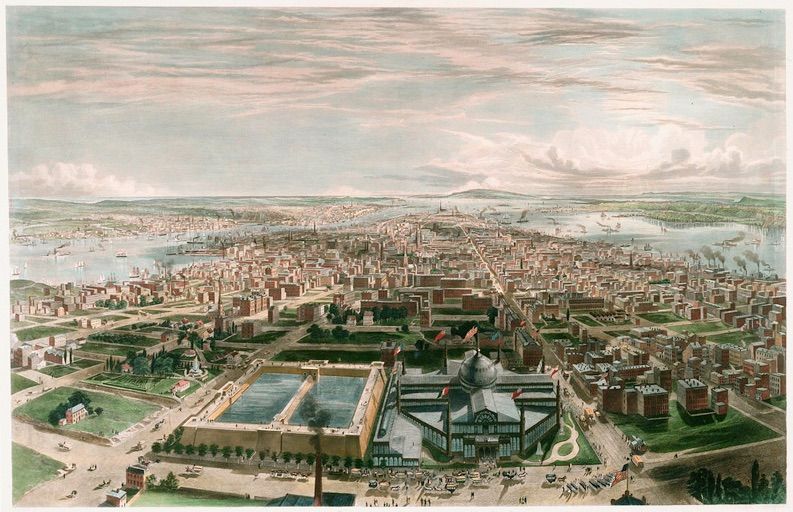

Next door, the Latting Observatory was called “New York’s first skyscraper.” Conceived by Waring Latting, the mostly wood tower rose 315 feet and was the tallest structure in New York City at the time. The tower had three landings, one at 125, 225 and 300 feet complete with telescopes where visitors could spy a panoramic look at Lower Manhattan, Queens, New Jersey and Staten Island. A New York Times reporter said of the observatory’s vista:

“We are told that our eyes could sweep from forty to sixty miles through space, and we scarcely doubt the assertion. We are certain of this fact, that nowhere in the world, civilization included, can such a view be obtained.”

Gustave Eiffel admitted that the inspiration for his centerpiece tower in Paris’s 1889 World’s Fair came from the Latting Observatory.

A

view from the top of the Latting Observatory. 42nd Street, Croton Reservoir and the Crystal Palace are in the fore. Hand colored lithograph done in 1855 by Benjamin Franklin Smith. Image from New York Public Library.

In Class 10 titled “Philosophical Instruments and Products resulting from their use (e.g. Daguerreotypes ) Maps and Charts, Horology, Surgical Instruments and Appliances” at booth number 1 visitors could see Samuel Morse’s patent electric telegraph in operation while at booth number 81 famed Daguerreotype artist / photography Mathew Brady was showing off a photograph of Admiral Matthew Perry.

All told, the Exhibition had over 1.1 million visitors before it closed on November 14, 1854. Unfortunately both of the fair’s famed structures were fire casualties. The Latting Observatory burned to the ground on August 30, 1856 when a fire from a nearby cooper’s shop on 43rd Street spread and overtook the structure. The Crystal Palace narrowly escaped that fire only to succumb to its own devastating blaze on October 5, 1858. The New York Times reported the fire to be “incendiary” starting in the lumber section of the palace.

New York would not play host to a world’s fair again until 1939.

You can continue to explore the history of the Crystal Palace in our first installment of Lost New York, a new virtual series now in our Insiders video archive! Unlock this archive of 100+ past events as an Untapped New York Insider starting at $10/month.

Next, read Buried Under Flushing Meadows is the 1939 World’s Fair Time Capsule, To Be Opened in 5000 Years and Vintage Photos: Remnants of the 1964 New York World’s Fair

Subscribe to our newsletter