NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

This article is by Jack Kelly, the author of Heaven’s Ditch: God, Gold, and Murder on the Erie Canal (St. Martin’s Press), a lively account of the canal and the many excitement generated along its banks that was published in July.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the Erie Canal made the Big Apple. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, a number of cities were competing to be the nation’s greatest port and commercial center. That honor depended on tapping the abundant supply of grain, lumber and other resources of the vast Middle West. The audacious, 360-mile waterway that New York State built between 1817 and 1825 solidified New York’s claim, pushing the city ahead of New Orleans, Baltimore and Philadelphia. Today, signs of that great project are scattered around New York, although the city itself is the greatest symbol of the canal’s phenomenal success.

Former Bank for Savings at 270-280 Park Avenue South at 22nd Street.

Former Bank for Savings at 270-280 Park Avenue South at 22nd Street.

New York State planned to finance the canal’s construction by issuing bonds. But the long ditch was a risky venture and neither commercial banks nor wealthy individuals were eager to take a chance. Canal backer Thomas Eddy suggested establishing a savings bank–the city’s first–to allow working and middle class families to invest in the project. The Bank for Savings was chartered in 1819, two years after canal construction began.

Founders predicted $50,000 of deposits in the first year. Instead, eager savers invested $155,000 in the first six months of the bank’s existence. The bank became the largest owner of canal bonds. Depositors were rewarded as the Erie paid off in spades. The bank inspired other savings banks and endured, through several name changes, until the 1990s. You can find one of its former locations at 270-280 Park Avenue South at 22nd Street, with “The Bank for Savings” still visible on the facade.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

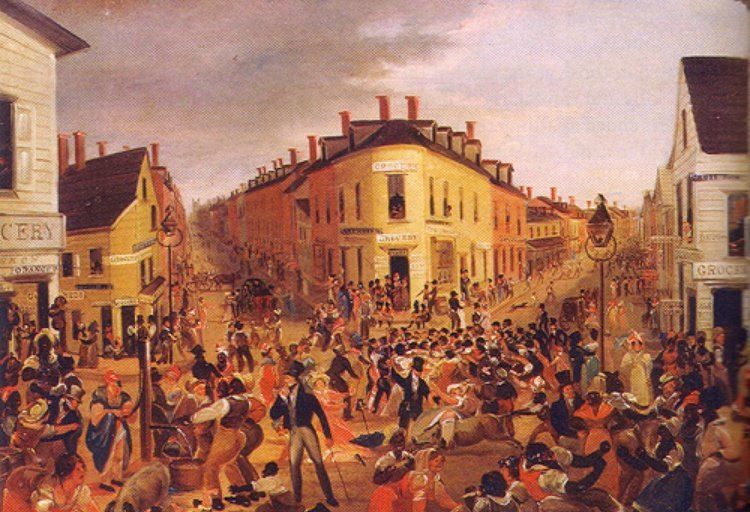

Local farmers were the first laborers to dig the Erie. But as the project moved to the sparsely populated western regions of the state, contractors increasingly hired Irish immigrants to heft the picks and shovels. Many of these workers came from the notorious Five Points district in lower Manhattan, just off Centre Street.

The Five Points, named for a distinctive intersection, was the most densely populated slum in the nation–perhaps in the world. Its level of unemployment, crime, disease and squalor were staggering. Canal workers earned less than a dollar a day for backbreaking labor, but many Irishmen jumped at the chance to get out of this urban hellhole.

Image from New York Public Library

New Yorkers have always known how to throw a party, and few public celebrations rivaled the one marking the opening of the Erie Canal. A flotilla of canal boats had made the trip all the way from Buffalo, carrying dignitaries and samples of inland produce A relay of cannon shots had announced to New York City residents the beginning of the group’s journey on October 26, 1817.

Ten days later, these boats led an “Aquatic Display” of decorated ships across New York Harbor. The “wedding of the waters” took place amid great ceremony at Sandy Hook as Governor De Witt Clinton poured a cask of Lake Erie water into the ocean. Then came a grand parade around the streets of lower Manhattan, viewed by the largest crowd to gather in North America to that time. A painted cask that held the ceremonial water can be seen in the collection of the New York Historical Society.

Grave of Robert Fulton, inventor of the Steamboat

Grave of Robert Fulton, inventor of the Steamboat

Fulton sailed the first commercial steamboat up the Hudson River in 1807, covering the distance from New York to Albany in 32 hours instead of the several days typical of wind-driven craft. Although steamboats were not allowed on the Erie Canal because their paddles eroded the channel, they became an indispensable link at both ends of the waterway, hauling produce along the Great Lakes and down the Hudson River.

Fulton died at age forty-nine in 1815 and was buried in the yard of Trinity Church. In 1901, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers erected a prominent memorial to the inventor in the churchyard. A nearby street is named for Fulton.

No one did as much to make the Erie Canal a reality as De Witt Clinton. A former Mayor of New York City, Clinton used his political skills to guide the canal proposal through a thicket of controversy to final approval. As governor, he oversaw the construction and completion of the great project. The canal’s success made his career and folks have talked of “Clinton’s Ditch” ever since.

Today, De Witt Clinton Park is a six-acre oasis on Manhattan’s West Side. The park contains the Erie Canal Playground, where a design on the pavement depicts the route of the famous waterway. The surrounding neighborhood, once known as Hell’s Kitchen, is now called Clinton.

If the Erie made New York City the nation’s busiest port, it also strained the city’s ability to handle the enormous influx of ships. With berths along the East and Hudson Rivers in Manhattan already crowded, businessman Daniel Richards proposed a modern enclosed harbor in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. Dredging what had been marshland, engineers constructed a basin unaffected by tides.

The harbor was soon crowded with ships and served by the many warehouses constructed around its edges. It opened in 1841 as traffic down the canal was surging.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

The most famous evangelist of the Erie Canal era was named Charles Grandison Finney. In 1830, Finney conducted the nation’s greatest revival, a six-month long prayer-fest in Rochester, right on the canal. It was so successful that Finney was lured to bring his inspiring message to the hordes in New York City. In 1832, his sponsors set him up in the cavernous 2,500-seat Chatham Street Chapel, a converted theater near the Five Points slum. A few years later, Finney moved to the Broadway Tabernacle, a specially constructed rotunda near present-day Worth Street.

Finney’s preaching became a fixture in the city. He also started several important reform movements that proved very influential. Drinking was rampant at the time, and Finney kicked off a major temperance campaign. His followers were also important in the early antislavery movement.

Hoping to maintain a tight grip on American grain shipments, New York State officials decided around 1900 to expand and modernize the Erie. They called the improved waterway the Barge Canal. In the 1920s, the state built a series of 54 grain silos in Red Hook, Brooklyn, to facilitate the trade. These 12-story concrete structures, architectural wonders of their time, could store millions of bushels of grain. Unfortunately, the amount of grain shipped through New York declined steeply during the twentieth century. By the 1950s, the Red Hook Grain Terminal was largely obsolete. Deactivated in 1965, it remains as monument to the prosperity the Erie Canal once brought to the city.

Barges were the main vessels to ply the waters of the Erie Canal. For decades they were pulled by mules. During the twentieth century, tugs took over. Today, a flavor of barge life can be found at the Waterfront Museum in Brooklyn, which is located on the only floating wooden covered barge of its kind, built in 1914. The museum is located along the Red Hook waterfront, right where Erie Canal grain barges lined up in the heyday of the canal.

Tin Pan Alley, the area around 28th Street and Fifth Avenue, is famous as the home of song writers and publishers. For more than half a century, beginning in the late 1800s, the name was synonymous with American popular music.

What’s the Erie Canal connection? In 1905 a Tin Pan Alley songwriter named Thomas Allen published sheet music for a tune called “Low Bridge, Everybody Down.” The piece begins, “I’ve got a mule and her name is Sal . . .” It became the classic Erie Canal song, offering a nostalgic look backward at a time when mules were being phased out. Pete Seeger, Bruce Springsteen, and countless millions of school children have sung the song down the decades.

Jack Kelly is the author of Heaven’s Ditch: God, Gold, and Murder on the Erie Canal (St. Martin’s Press), a lively account of the canal and the many excitement generated along its banks. Next, read about the Secrets of Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal.

Subscribe to our newsletter