Morningside Park is experiencing something of a renaissance in recent years, with booming real estate in Morningside Heights and Harlem surrounding it. The picturesque park seems to have it all – grand landscapes, practical outdoor amenities, landmarked architecture, and commanding views.

Today, we’ll go through some of the most fun secrets and fun facts we came across while researching for a talk we gave with the Design Trust for Public Space inside Morningside Park last week.

10. Morningside Heights is Built Atop Manhattan Schist Up to 30 Million Years Old

The rocky terrain of Morningside Heights is full of rocky Manhattan schist, some which dates to over 30 million years ago. The area was previously settled by the Harlem Plain Indians, who called the area Muscoota, and was later settled by the Dutch and called Vandewater Heights, named after a Dutch settler. You can still find the glacial outcroppings throughout the park however – some of it even supports PS 36.

9. Morningside Park Was Not Part of the Manhattan Street Grid

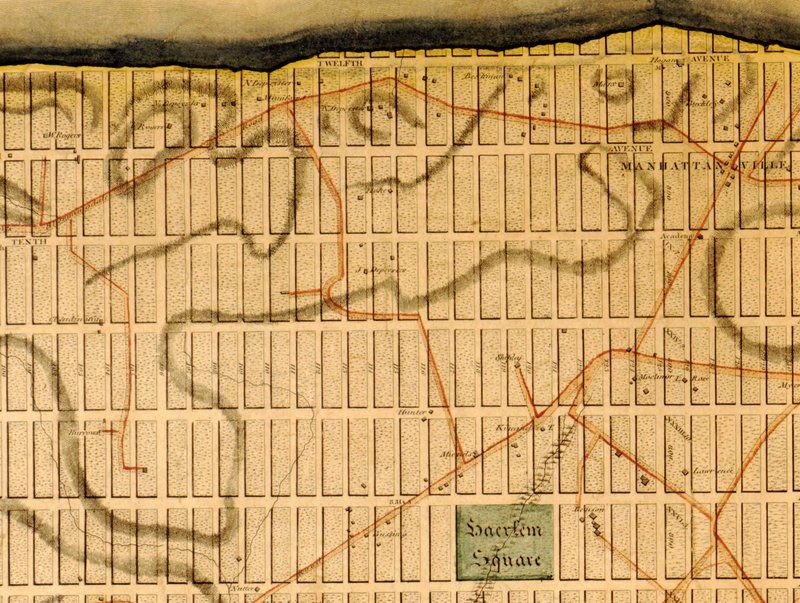

Portion of the Commissioner’s plan for New York City. Image via Library of Congress.

If the Commissioners of New York City could have had their way, the Manhattan street grid would have extended through what is now Morningside Park. But the park is one of the many exceptions to the Manhattan street plan of 1807. In the late 1860s, the Commissioner of Central Park, Andrew H. Green, put forth the idea for Morningside Park, arguing that it would be very costly and very inconvenient to extend the Manhattan street grid over this topography. Green wrote that “the ridge of rocks is almost vendureless, breaks so abruptly towards the east as to render the streets that have been laid over it in rigid conformity with the plan of the city, very expensive to work.”

8. There Has Only Been One Road to Ever Go through Morningside Park, And It’s Long Been Lost

During the American Revolutionary War, the Battle of Harlem took place in the area in September 1776. A plaque on the mathematics building at Columbia University commemorates this battle, which was a morale turning point in the American Revolution for the Patriots. The majority of the action occurred west of here however, from 106th Street to 120th Street between Broadway and Riverside Drive. Colonial soldiers were able to retreat on a road that ran through today’s Morningside Park, the only road ever known to go through it.

7. Until a Few Decades Ago, There Was a Blockhouse from 1812 in Morningside Park

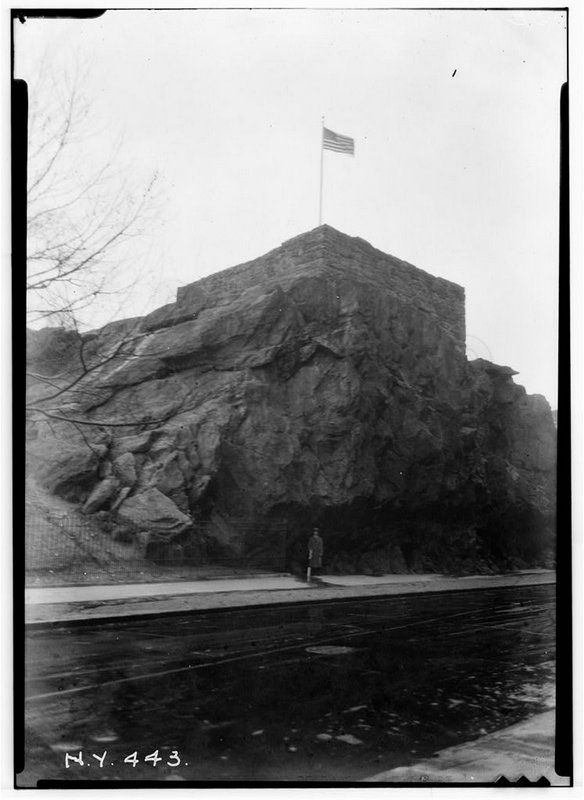

Blockhouse from War of 1812 in Morningside Park. Photo from Library of Congress.

Blockhouse from War of 1812 in Morningside Park. Photo from Library of Congress.

A blockhouse was built on top of a glacial outcropping in what is now Morningside Park as a military fortification for the War of 1812 against the British. It was one of three built here, similar in style to the one that still stands in Central Park. This one in Morningside Park was torn down a few decades ago. However, you can still see the glacial outcroppings at

Some of the glacial rocks underpinning PS36

6. Morningside Park Had a Vastly Different Original Plan

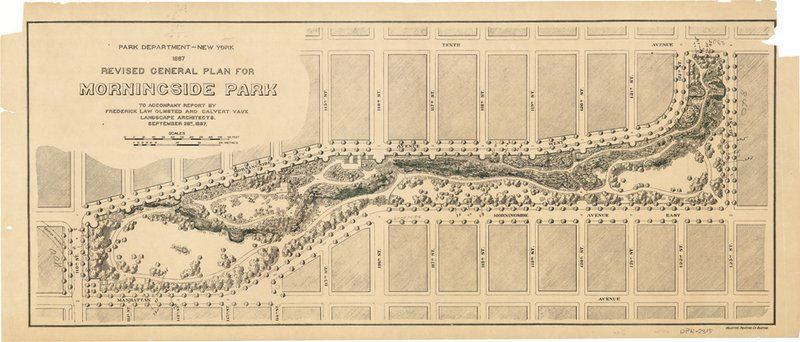

Olmsted and Vaux Plan for Morningside Park. Image via NYC Municipal Archives

New York City was given this property in 1870 and plans were drafted up by numerous architects, including Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, who designed Central Park. Olmsted’s plans conceived of the park as a quasi-extension from Central Park, and he designed a grand entrance at the southeast corner. His plan aimed to take advantage of the views out to Long Island Sound, and included a tropical garden, a chalet, a building for a zoological collection and a winter garden.

5. Some of NYC’s Most Famous Architects Worked on Morningside Park

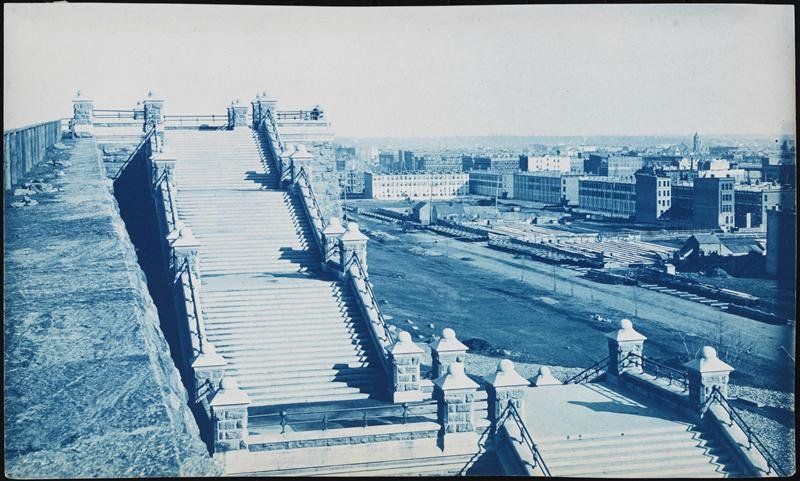

Photo from the Museum of the City of NY

All of the plans for Morningside Park were rejected, and Jacob Wrey Mould was hired to rework Olmsted and Vaux’s designs. Mould also worked on Central Park, producing some of the most notable buildings including Belvedere Castle and the structure which houses Tavern on the Green. He also worked with Vaux on the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History.

The esplanades, steps and masonry walls in Morningside Park were actually part of Mould’s design not Olmsted and Vaux. After Mould died, Olmsted and Vaux were rehired to finish the project in 1887. Most of their contributions are related to the landscaping and vegetation – as they planted trees and bushes that could survive in this rocky environment.

Vaux continued to work as a consultant on the park until 1895, when he drowned in Sheepshead Bay, an incident that was rumored to be a suicide. New York City Parks Superintendent Samuel Parsons Jr. wrote that “No landscape architect who ever lived had a finer sense of the right adjustment of rocks in a park than Mr. Vaux…perhaps Morningside Park was the most consummate piece of art that he had ever created.”

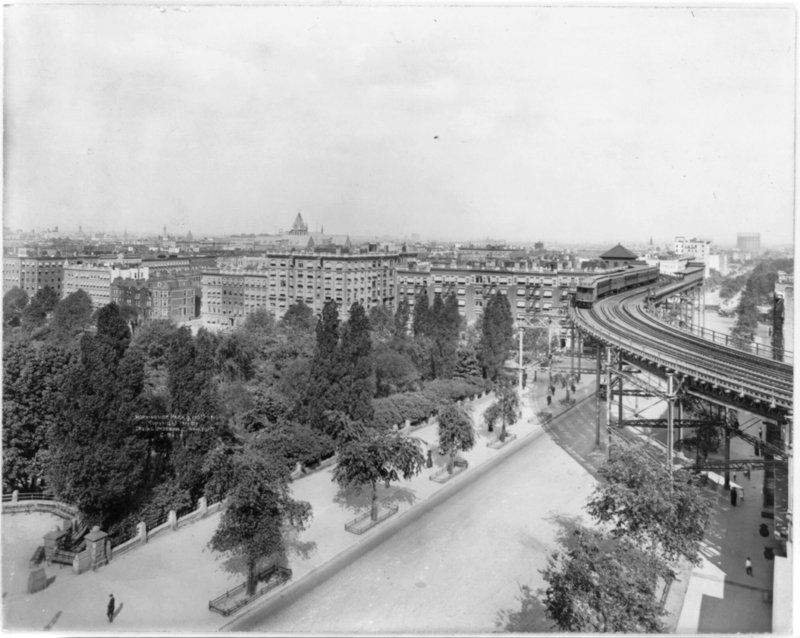

4. There Used to be an Elevated Railway Next to Morningside Park

Photo from Library of Congress

The 9th Avenue elevated line was part of the first elevated railway in Manhattan. A portion of this elevated rail was added in the late 1870s, extending from 104th Street and Columbus Avenue. The line went east on 110th Street, from where the above photo was taken, and north up Eighth Avenue to 125th Street. The curve at 110th Street was the highest ever built and dubbed the “Suicide Curve,” because of the number of people that jumped from there.

3. There Was a Massive Columbia University Protest Over a Gym in Morningside Park

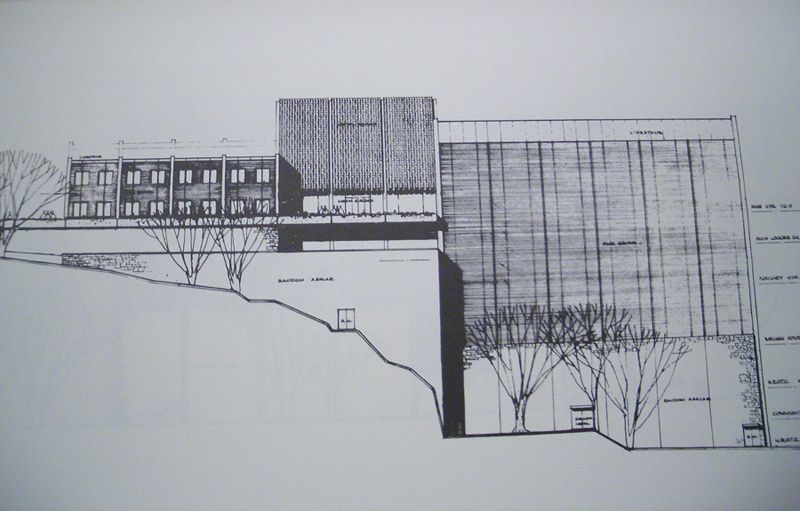

Plans for the Morningside Gym. Image via WikiCU, user Tao tan

In 1968, a large protest took place at Columbia University, stemming from the potential construction of a gym in Morningside Park. The reason for the protest stemmed from this key fact:

It had two doors, one for Harlem community residents who were predominantly black and one for students who were predominantly white. The door for community residences was in the back of the gym on a lower level, while the door made available to students was a grand entrance in the front of the gym. The plans were announced the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, only adding to the tension already in the air. On top of all of this, Columbia professors were heavily involved with weapons development research for the Vietnam War, a war wildly unpopular on college campuses. With this in the background, the proposal for segregated doors was a recipe for disaster.

The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and Students for Afro-American Society (SAS) led these protests. They joined forces and held a rally, which then turned into a university-wide, week long student protest. The protest was non-violent at first, but by the end of the week police were sent to stop the demonstration. Protestors tore down the fence around the construction site and occupied four academic buildings. After negotiations to change the gym/Vietnam policies failed, this protest turned into a student strike big enough to convince administrators to cancel all plans for the gym and terminate all ties with Vietnam weapons research.

2. The Remnants of the Gym Were Converted into a Pond and Waterfall

As a result of the protests, about 30 acres of Morningside Park languished for three decades. It wasn’t until 1989 that new construction commenced turning the excavated foundation for the gym into a pond and waterfall. The picnic area, rebuilt ballfields and other changes were also made in this renovation.

1. The Saga of the Statue of Lafayette and Washington in Morningside Park

A bronze statue of Lafayette and Washington, a replica of one made by Frederick Bartholdi who designed the Statue of Liberty, stands in Lafayette Square in Morningside Park. The original was commissioned by Joseph Pulitzer, head of the New York World newspaper, whose main office was the tallest building in the world at the time. Pulitzer was excited about the work of art that would commemorate Franco-American relations but the New York Times criticized the work excessively, apparently for the incorrect height of Washington. They wrote:

A more serious objection to the group is the mistake M. Bartholdi has made in the relative size of the two heroes of the Revolution. Washington was a man of exceptional height, that majesty of deportment which every one who saw him noted as a chief characteristic was not merely the result of his large and commanding mind, but was reinforced by the bigness of his physical make-up. Americans are good-humored, but they will not care to allow even so notable a sculptor as M. Bartholdi an artist’s license in this respect, because it violates too obviously the actual facts.”

So instead, Pulitzer gave the statue to the city of Paris in 1895 where it stands in a park on Rue des Etas Unis. Meanwhile, the New York City merchant Charles Broadway Rouss purchased a replica of the Bartholdi statue and donated it to the City of New York. In 1900, it was unveiled in Morningside Park at Lafayette Square. At that point, The New York Times decided to be conciliatory, writing “The group has been erected in a position which displays it in a more conspicuous manner than the majority of the public statues of the city.”

Next, discover the Top 10 Secrets of Central Park and 15 Secrets of Columbia University.