Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

For over 70 years, Sixth Avenue has not been the official name of the avenue that can be found between Fifth and Seventh Avenues in Manhattan. On October 2nd, 1945, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia signed a bill ceremoniously renaming Sixth Avenue the Avenue of the Americas. Prior to that, Sixth Avenue had been the street’s name since April 1, 1811, when it replaced West Road. The City’s goal at the time was to display Pan-American friendship but almost immediately, many New Yorkers were opposed to the new name, both actively and passively.

In September 1945, when the ink was not yet dry on the City Council’s bill, there were attempts to undo the legislation. In 1955, The New York Times conducted an “impromptu survey” finding that Sixth Avenue was favored over Avenue of the Americas by a margin of 8.5 to 1. By 1965, the Avenue of the Americas Association, presented joke awards to those that had resisted switching to the new street name for over two decades. The winners included a taxi driver (on behalf of all tourists), the Sixth Avenue Deli, the editor of New Yorker and ironically, the Executive Vice President of the Avenue of the Americas Association (who had not changed the organizations name in the telephone book from the Sixth Avenue Association). The winners received a plaque and a ninepin, symbolizing Rip Van Winkle’s two decade slumber.

By 1985, Mayor Ed Koch ordered the Sixth Avenue back on the Avenue’s street signs. Since most New Yorkers are still reticent to refer to the street by its official name, a number of objects placed along the street in commemoration of its name are overlooked or their context is unknown.

Presented below are 10 objects that complement Sixth Avenue’s official name, Avenue of the Americas:

At 11:30 on Tuesday, May 18, 1965, the statue of Cuban patriot and martyr Jose Julian Marti statue was dedicated (with a performance by the Department of Sanitation Band). The statue had a long and complicated journey to its dedication at the northern end of the Avenue of the Americas. It was the last major equestrian commission by artist Anna Hyatt Huntington, at the age of 80. Huntington was personally recruited to sculpt Marti by the Cuban Government, under Batista. She was paid $100,000 for the work, which she donated to hispanic charities. The statue was completed in May 1959 but it would take six more years for the statue to be erected.

For six years, an empty plinth stood next to the statues of San Martin and Bolivar on 59th Street. Huntington’s statue was given to the City in November 1958 or May 1959 (depending on the source) after which point it disappeared. In 1960, the Marti statue was discovered in a Bronx storage yard, strategically hidden under a tarp. The City, at the behest of the State Department and NYPD, refused to erect the sculpture out of fear it would become the site of clashes between pro and anti Castro groups. As a result of the City’s inaction, a group of Anti-Castro Cuban exiles attempted to erect a plaster model of the statue atop the plinth. Ultimately, the 600 pound statue proved too tall to hoist atop the base and it was placed next to it, with the hope that it would be too heavy for the police to move. Within hours, the police arrived and somehow confiscated the statue (as they more recently did with the Snowden and Trump statues).

By April 1965, the statue was rediscovered in a Central Park maintenance yard. When asked about its present predicament by The New York Times, a spokesperson from Mayor Robert F. Wagner’s office responded “How come you guys know where it is?” The City finally decided it was time to finally erect the sculpture. On May 18, 1965, the 70th anniversary (plus one day) of Marti’s death, the statue was dedicated in the presence of Anna Hyatt Huntington and Cesar Romero (Marti’s grandson and the actor best known for playing the Joker in the Adam West Batman series).

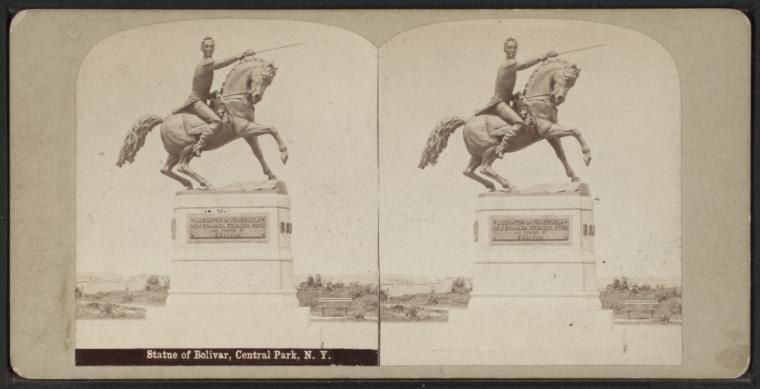

The northern terminus of the Avenue of the Americas at Central Park is flanked by the statues of three South American revolutionaries. The first of these South American heroes to be honored was Simon Bolivar. In 1884, the people and Government of Venezuela gifted a statue of Bolivar to Central Park. The statue stood near 81st Street, on the west side of the park, on what became known as Bolivar Hill. The statue, designed by R. De Las Cora, was not well received and was removed from the park.

The Original Statue of Simon Bolivar, Central Park via NYPL

The Original Statue of Simon Bolivar, Central Park via NYPL

In 1921, President Warren Harding presided over the dedication of a new statue of Bolivar on Bolivar Hill, designed by Sally James Farnham, whose work can also be found at Woodlawn Cemetery. With the creation of the Avenue of the Americas, the Venezuelan Government requested that the statue be moved to a more prominent and contextually appropriate location. Initially, the Art Commission denied this request, despite pressure from the State Department, and instead voted to improve the site where the statue was located. It took until 1951 for the statue to be moved to its current location, paid for by the Government of Venezuela.

The 1950 statue of General Jose de San Martin was a gift of the City of Tucuman (or alternatively Buenos Aires). San Martin aided Argentina, Chile, and Peru in gaining independence from Spain. The statue was given in reciprocity for a statue of George Washington that the people of North America had given to the City of Buenos Aires a few years earlier. The statue of San Martin is a replica of Louis Joesph Daumas’ 1862 statue of San Martin, located in Buenos Aires.

The statue was made in Argentina and shipped to New York aboard the Rio Chico. However, once it arrived in New York, the statue remained in limbo – first at the pier and then in an unopened crate in a warehouse in Central Park because Mayor O’Dwyer was having issues convincing the Board of Estimates to appropriate the funds to erect the statue. Its placement at the foot of Central Park led to infighting between Robert Moses, then Parks Commissioner, and City officials. Even the State Department got involved, using the City to place the statue in a prime location to aid Pan-American relations.

Today, there is a push by the Friends of Jose Marti to erect a replica in Havana.

In 1951, Brazil offered its own contribution to the Avenue of the Americas, a statue of Jose Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva, who was also known as the patriarch of Brazilian independence. Mayor Impellitteri accepted the Brazilian statue, with the understanding that Brazil would pay for the entire cost of its construction and erection.

The Andrada statue was designed by Jose Otavio Correia Lima, a Brazilian Sculptor and made in Brazil. The nine foot tall bronze statue was unveiled in the northwest corner of Bryant Park in 1955, in the presence of Mayor Wagner, the Brazilian Ambassador, and Robert Moses. The invocation was delivered by Cardinal Spellman and the Brazilian and American national anthems were played by the Department of Sanitation band.

In 1959, two 400 watt floodlights were dedicated to light up the statue by the Avenue of the Americas Association. The great-great-grandsons of Andrada and William Cullen Bryant were both present.

But for the NYC Art Commission, Andrada’s statue might have languished in a Parks Department warehouse. When Bryant Park was remodeled in the late 1980s, the plan did not initially provide for a location for the statue. As a result, the Art Commission voted down the plan until a new site was given to the statue. Today, the statue can be found on the Avenue of the Americas between 40th and 41st streets.

On October 9th, 2004, the Avenue of the Americas received its newest addition to commemorate its intended goal of Pan-American friendship. The statue depicts Benito Juarez, a Mexican national hero who served as its first indigenous president. The Mexican State of Oaxaca gifted the statue to New York City, and its governor, Jose Murat, presided over the statue’s dedication with New York City Parks Commissioner, Adrian Benepe. The statue of Juarez, designed by Mexican sculptor Moises Cabrera Orozco, is the first statue of a Mexican and the first statue of a non-fictional indigenous person in a New York City park.

The statue of General Jose Artigas can be found in SoHo Square, a small triangle of green bounded by the Avenue of the Americas (to the east and west) Spring Street (to the north), and Broome Street (to the south). Artigas is known as the father of Uruguayan independence, though he did not live to see his dream of an independent Uruguay become a reality. The statue is a copy of one designed by Jose Luis Zorrilla de San Martín located in Montevideo. The Artigas statue was presented to New York City as a gift from the Urugay in 1997.

The statue of Juan Pablo Duarte can be found in the aptly named Duarte Square. Duarte, one of the founders of the Dominican Republic, was honored with a bronze statue designed by Nicola Arrighini in 1978. The Dominican Republic donated the thirteen foot statue of Duarte to New York City on the 165th anniversary of Duarte’s birth.

In addition to the statues, one Midtown street was renamed in recognition of the lofty goals of Pan-American friendship espoused by the name, Avenue of the Americas. West 46th Street, situated between Fifth Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas was renamed Little Brazil Street in 1996. The street was renamed in honor of more than 500,000 Brazilian immigrants living in the United States, close to a fifth of which live in New York City. At the time, there were numerous Brazilian establishments located along the block. Today, with the exception of Brazilian Day on September 4th, few remnants remain of the street’s vibrant Brazilian past.

In 1959, John H. Muller, the finance chairman of the coats-of-arms committee of the Avenue of the Americas Association, presented Mayor Robert F. Wagner with a reproduction of a shield bearing the coat of arms of the Organization of American States. This was the first step in a goal to place the three foot porcelain enamel shields on 300 light posts along Sixth Avenue. The 300 shields were to display the coats of arms of each of the twenty-two nations in the Western Hemisphere. It was thought that placing the shields “can only do good” given the economic and political uncertainties of the time in some of the South and Central American countries and because “no one in his right senses – outside the Communist fold – wants deliberately to be on bad terms with the United States.”

Today, only 22 of the original 300 remain, a casualty of a lamp replacement program in the early 1990s. Walking along the street you can no longer find shields representing countries including Mexico, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Jamaica, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico and El Salvador and others such as Canada, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Surimane depict out of date versions of their countries shields.

Playground of the Americas can be found on West Houston Street between MacDougal Street and Avenue of the Americas. It was acquired in 1925 by the City and given to the Parks Department in 1934. The barely hundredth of an acre park did not have a name until 1998 when it became Houston Plaza, which was short lived. In 2000, the park became Playground of the Americas, in honor of the Avenue’s official name.

Next, explore NYC’s 6½ Avenue and discover the smallest parks in Manhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter