10 Giant Menorahs That Will Light Up for Hanukkah in NYC

From Brooklyn to the Bronx, we’ve rounded up the most exciting giant menorahs that will light up throughout the next eight evenings!

Much has been written about the “what” and the “where” of Robert Moses’ grand vision and achievements – the bridges, the parkways, the beaches, the pools, the dams, and the mass housing projects have all been thoroughly dissected by many authors and historians. However, much less has been written about the “how”, the “why”, and the “what if.” How was he able to be the most powerful unelected official in our country’s history? Why did he favor the automobile and turn his back on mass transit? What if he hadn’t built the infrastructure, for better or worse, that New Yorkers deal with everyday?

BLDZR: The Gospel According to Moses, is a rock musical that explores the intimate tale of this man, and through his triumphs, his loves, and his losses reveals a highly-intelligent, complex, yet deeply-flawed individual whose legacy in cement and steel will shape the New York landscape for years to come. Untapped Cities previously reviewed its first debut earlier this year, and we called is “supremely entertaining.” This fall, the show will return to the Triad Theater on West 72nd Street for a three night run on October 20th, 21st and 22nd. Tickets are available here.

Work on the bridge was started in 1929, but was soon halted because of the Depression. The Triborough Bridge was originally intended to enter Manhattan at East 103rd Street (approximately due west of its Queens entrance). A few years later, when the project was restarted, it came under the direction of the New York State WPA of which Robert Moses was the chairman, and the Manhattan entrance was quietly moved to East 125th Street. This change added 2.5 miles of additional distance for every trip between midtown Manhattan and Queens (5 miles for a roundtrip). Since it’s opening in 1936, that’s a lot of extra miles.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Throughout his career, Robert Moses was someone who never really listened to other people’s opinions, but by 1950 he was physically going deaf. His aides even installed an amplifier in his phone and microphones throughout his office with small speakers placed near his desk to pick up conversations and help him hear better. It didn’t help much. For many years he was too vain to wear a hearing aid, and subsequently couldn’t hear most of what was said to him, or about him, in meetings, interviews, and events. Moses’ habit of assuming that everyone was in agreement with him was probably a result of both his personality and his growing audio isolation.

Image bottom from Library of Congress, photo of Robert Moses from The Metropolitan Transportation Authority Bridges and Tunnels Special Archives, photo of Jane Jacobs from Wikimedia Commons

Early in her career, Jane Jacobs was a writer for Architectural Forum, but it was a freelance article that she wrote for Fortune Magazine criticizing Robert Moses that brought her to the attention of the Rockefeller Foundation. Subsequently, she was given grant funding by the Rockefeller Foundation to research and review U.S. city planning and to produce critical analysis and white papers for the Foundation’s Urban Design Studies research program. This research would become the basis of the her seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

It’s highly likely that Nelson Rockefeller was well aware of Jane’s writings in opposition to Robert Moses’ urban renewal practices at the time that Rockefeller was negotiating the MTA/TBA merger with Moses. And while Rockefeller may have viewed the merger as a way of appealing to urban voters and raising his public profile for an anticipated presidential run, he may also have known that a healthy mass transit system was absolutely essential to sustaining New York’s future viability as the world’s greatest city.

More than fifty years later, the Rockefeller Foundation is still involved in promoting the work of Jane Jacobs. In 2012, Michelle Young, the founder of Untapped Cities helped organize the conference, Jane Jacobs Revisited at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in Italy, with Kate Ascher, author of The Works, and Mary Rowe of the Municipal Art Society. See a video about that conference here.

Nelson Rockefeller. Image via Wikimedia Commons, Library of Congress

Robert Moses first met Nelson Rockefeller through his work on the Palisades Parkway, which was built on land donated by the Rockefeller family in the 1930s. After many years working on a number of Rockefeller projects in South America, and also in developing a business relationship with Chase Bank president David Rockefeller (who financed most of the bond issues for Moses’ projects), Moses felt a certain affinity and kinship with the Rockefeller family. Nelson Rockefeller was probably one of the few people who Moses felt was his equal, and when Rockefeller became New York State Governor, Moses treated him with a level of respect that he had previously only given to his mentor Gov. Al Smith. It was this familial trust and respect on Moses’ part that eventually enabled Rockefeller to oust Moses from power.

When the Manhattan entrance of the Triborough Bridge was moved to East 125th Street, guess who owned that property? That’s right, WR Hearst owned all of the land required for the Manhattan Triborough Bridge entrance and approach roads at East 125th Street, and he was paid handsomely for the land by The Triborough Authority. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, Robert Moses received constant unquestioningly positive publicity from all of Hearst’s New York publications. Some of this publicity was certainly warranted for the many projects Moses built for the benefit all New Yorkers (i.e. renovating Central Park, building Jones Beach, opening 12 municipal pools in one summer, etc.), but could this business deal for a previously unremarkable parcel of land have influenced editorial policies and attitudes towards Moses? By the 1950s public opinion, journalistic skepticism, and Hearst’s news empire had all begun to change, along with Moses’ reputation. Hmmm…

Robert Moses held onto seemingly unchallenged power for over four decades, through the administrations of 6 mayors, 5 governors, and several presidents. How? The lowly tollbooth gave Moses a never-ending cash flow that was used as collateral for the bond issues he needed to finance his projects. But what made his highway and bridge tollbooths even more powerful was the fact that in the early 1920s when he had been Gov. Al Smith’s chief of staff, Moses himself had stealthily rewritten the New York State legislation governing public authorities.

Prior to this, a public authority was typically a 40-year entity, based on the time it took to pay off the bonds that financed the structure, at which point the toll was eliminated. Moses’ legislation re-invented public authorities as open-ended entities, collecting tolls long after the authority’s financial obligations to its bondholders had been paid. And what made this an even more powerful tool was that the cash flows on Moses’ bridges and highways were always increasing as “car culture” took over 20th century America. All of this, in combination with three phases of federally-subsidized financing – the WPA program in the 1930s, the Title I urban renewal program in the 1940s, and Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway initiative in the 1950s – generated a perfect wave of funding that Moses was able to ride high on for almost 40 years.

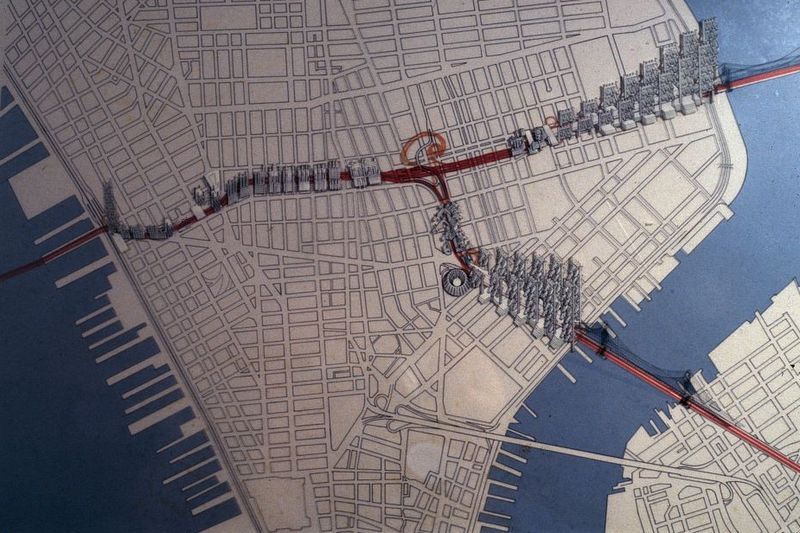

Proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) that was never built. Image from Library of Congress

It wasn’t so much that he opposed public transportation, but more likely that he was enamored with all things automobile related. Coming of age in the 1900s and 1910s, Moses viewed the private automobile, as many people did at that time, as an exciting new technology that was a vast improvement over the day’s standard horse and buggy carriage. It was an era where newness and expansion were the driving forces of American commerce. Sustainability and environmental issues were not yet part of the public discussion.

Much like the computer and the Internet today, the car was the disruptive technology of its era, the must-have device of the 20th century. The downside of its subsequent growth and dominance over the transportation industry, and the repercussions of the urban decay and suburban sprawl brought on by this new “car culture” were not fully understood for decades to come. Is this possibly a cautionary tale for our current digitally oriented consumer infatuations?

While Moses often cited Parisian planner Baron Haussmann as a like-minded source of inspiration, it was really the modernist Le Corbusier whose theories of urban planning as applied to housing and transportation that Moses most aspired to. Le Corbusier’s failed dream of “cleaning and purging” cities was a close cousin of Moses’ own “scythe of progress” mentality towards urban renewal.

With no formal architectural or engineering background, but highly educated at Yale, Oxford, and Columbia, Moses’ forte was not in designing or planning but in finding the resources to carry out grand visions of often marginally aesthetic value. His knowledge of the arcane machinations of government policy, the ways and means of bureaucratic administration, and a natural ability to manipulate, coerce, and abuse those who worked with him and for him was his true genius. His ideas about cities were always focused on vehicular traffic, and not on the messy business of pedestrians. As Moses was once quoted saying, “I like the public, the people… not so much.”

Next, see more about BLDZR, the upcoming musical about Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs and get tickets to the show. Then, check out 5 things we can blame on Robert Moses.

Subscribe to our newsletter