Three million people have been buried in New York City’s Calvary Cemetery since its establishment in 1848. Spanning 365 acres across Maspeth and Woodside, the visually famous site contains the largest number burials of any cemetery in the United States, one of our favorite secrets of the city. New York City’s famous skyline, jaggedly rising and falling in the background, eerily parallels the lines formed by the endless rows of headstones decorating the grounds. Both elements are crowded, but organized – and perhaps those qualities are what make the Calvary Cemetery so intrinsic to city it was founded upon – and so picturesque for the countless movie and television series that have been filmed there. No wonder it never fails to pique our interest.

10. There’s a New York City Park Inside Calvary Cemetery Full of Civil War Dead

In 1863, the City of New York purchased the land from the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and granted Parks jurisdiction over it. The Calvary Veterans Park, as the site was called, was used as a burial ground for Union soldiers who passed away inside New York hospitals after fighting in the Civil War. It is one of many public parks that serve as a burial ground (Pelham Bay Park, Prospect Park, Van Cortlandt Park, etc.), although the only New York City park completely surrounded by a cemetery.

Twenty-one Roman Catholic Civil War Union soldiers are interred there with the last burial taking place in 1909. The soldiers were buried free of charge thanks to the church, which offered to cover the costs for those who could not afford the burials.

Today, the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation is responsible for the maintenance of the statuary and the Civil War Memorial, erected in 1866, which features bronze sculptures by Daniel Draddy.

9. Calvary Cemetery Was Established Because of Overcrowding

By turn of the 20th century, Manhattan’s population had jumped to almost two million people. Real estate soon became a commodity that was too valuable to set aside for the dead. This prompted the legislature to approve the 1847 Rural Cemetery Act, which allowed nonprofit organizations like churches to purchase tax-exempt “rural” land for burials. Prior to this law, the deceased were interred in churchyards or private properties.

Although a limitation was placed on the amount of cemetery land that could be purchased in one county, institutions – looking for a way to circumnavigate this restriction – began to purchase burial space on the border between Brooklyn and Queens.

Calvary Cemetery, named after the hill where Christ was crucified, consequently became the first major cemetery to be established beyond Manhattan by the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. On July 31, 1848, the first burial took place, and Esther Ennis, who reportedly “died of a broken heart,” was interred at the site. That same year, Archbishop John Hughes consecrated the graveyard in August.

8. Divisions of the Calvary Cemetery Correspond With Ancient Roman Catacombs

Calvary Cemetery is comprised of four major sections: the First (Old), Second, Third and Fourth Divisions, formally known as the Divisions of St. Callixtus, St. Agnes, St. Sebastian and St. Domitilla. Each name corresponds to one of forty or so ancient Roman catacombs, some of which date back to the second century A.D. In response to the shortage of land in Rome, these underground cemeteries were used by Hebrews and early Christians to bury their dead; they are now accessible to the public.

7. Calvary Cemetery is Part of the “Cemetery Belt” in New York City

In the 1830s and ’40s, a series of outbreaks (typhus, cholera, etc.) had plagued New York City, causing a huge spike in the number of deaths. Fearing the diseases from the buried deceased would contaminate the drinking water, the Common Council prohibited new interments of the departed in Manhattan in 1852.

The new regulation, coupled with the effects of The Rural Cemeteries Act of 1847, eventually lead to the establishment of the “Cemetery Belt,” a string of cemeteries (including Calvary Cemetery and the many along the Jackie Robinson Parkway) along the border of Brooklyn and Queens that is large enough to be seen from space.

6. There Was Once a Thriving Neighborhood Between Calvary Cemetery and Newtown Creek

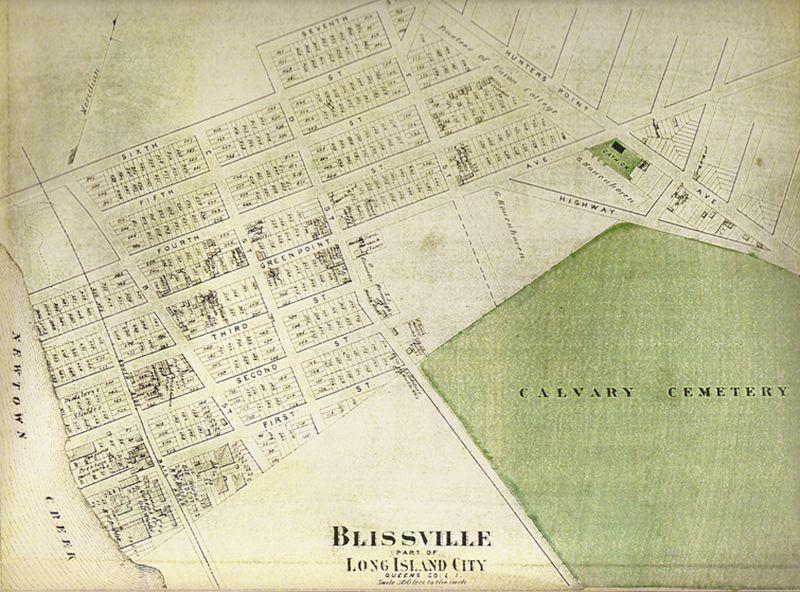

Image via Wikimedia Commons from Greater Astoria Historical Society

Blissville, a tiny neighborhood located between Calvary Cemetery, the Long Island Expressway and Newtown Creek, is named after Neziah Bliss, a steam engine developer and apprentice of Robert Fulton, who owned the majority of the surrounding land in the 1830s and 1840s.

Until 1848, the year the Calvary Cemetery officially opened its gates, Blissville was nothing more than an outpost. The neighborhood, however, flourished back to life as people traveled to the area from Manhattan to bury their dead. Soon enough, it became known as the gangway for deceased New Yorkers to reach the afterlife.

Today, not much of the neighborhood remains aside from a single residential block of pre-WWII era family homes. Nearby, warehouses and auto body shops line the streets.

5. Calvary Cemetery Was Used in The Godfather and Other Films

According to Ed Glazar, the author of Bike NYC, Vito Corleone in The Godfather was buried at an accessible site inside the Calvary Cemetery. Here are his instructions to get there:

“Start at the entrance to Calvary Cemetery (33-52 Greenpoint Ave between Bradley and Gale Aves, Long Island City, Queens; 718-786-8000) at Gale Avenue. Ride through the gate onto St. Johns Avenue. Cross St. Mary’s Avenue and drop down the hill to Section 6. Follow the road to the left of the mausoleum and stop in front of the Hildreth and Gary vaults on your right. Look to the bank of headstones opposite; this is the site where Vito Corleone was buried in The Godfather.”

Calvary Cemetery has appeared in numerous films and television series, including Zoolander, Gotham, The Night Of, Jessica Jones, Daredevil and much more.

4. The Johnston Mausoleum is the Largest Personal Mausoleum in Calvary Cemetery

Built and occupied by the Johnston brothers in the 19th century, The Johnston Mausoleum is the largest personal mausoleum (and the third-tallest building) in the cemetery, costing over $100,000 to construct at the time (or roughly $2.5 million when adjusted for inflation). Thirty vaults are built into the marble, although only six interments took place.

The brothers operated J.C. Johnston silks and fabrics store on 22nd Street between Broadway and 5th Avenue, which was largely successful at the time. The mausoleum, however, was built before the last of the Johnston brothers squandered the family fortune and passed away in a barn.

3. There Are Regularly Scheduled Masses at Calvary Cemetery

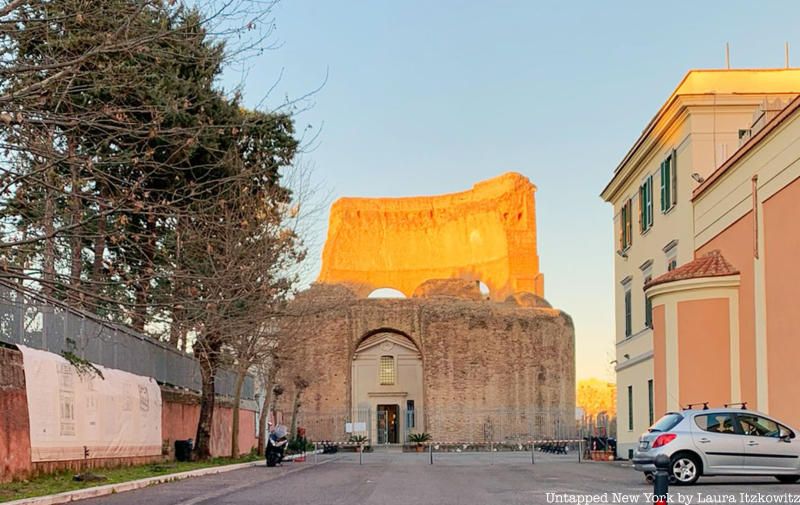

A unique limestone chapel, constructed by Raymond Almirall in 1895, features bas relief carvings and a granite statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Inspired by Italian churches and mortuary chapels, the building stands in the First Calvary and serves as the site of regularly scheduled masses, including the Eucharist, which is celebrated for those buried within the cemetery. Originally, it was also intended to serve as a burial crypt for New York City’s parish priests.

2. The Gate of Calvary Cemetery is Named After an Early Pope

The gate of Calvary Cemetery was erected over forty years after the cemetery was first founded. Built by an unknown architect, it is inscribed with the name St. Calixtus, an early pope and the patron saint of cemetery workers, who was martyred for his beliefs.

1. Many Headstones at the Calvary Cemetery Cite a Place of Birth

Rosemary Muscarella Ardolina, in producing her book (Old Calvary Cemetery: New Yorkers Carved in Stone), searched through the Old Calvary Cemetery and transcribed headstone inspirations which were legible, those which cite a place of birth and those of veterans of the Civil and Spanish-American wars. Of the 5,315 transcriptions, she found that 90% of the headstones cite Irish places of birth; various other countries, including the United States, Italy, France, Scotland and Canada were also spotted.

Next, check out 14 of NYC’s Smallest Cemeteries, discover Hart Island, NYC’s Mass Burial Ground for the Poor and Indigent, and Cities 101: New York City is Running out of Room in Cemeteries for Its Dead.