After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

Very few places in New York City offer a quiet refuge away from the chaos of everyday city life. The Cloisters, nestled inside Fort Tryon Park, is one such getaway, which specializes in European medieval architecture and decorative arts. As the much lesser known branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the museum is very much a hidden gem – and maybe, that’s for the best.

The construction of The Cloisters took place over the course of five years, beginning in 1934. Philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, who commissioned Fort Tryon Park, brought several hundred acres of the New Jersey Palisades to help preserve the view from the museum. This scenic span of land was later donated to the State of New Jersey, and is now part of Palisades Interstate Park, although recent construction has sparked controversy.

Image in public domain from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

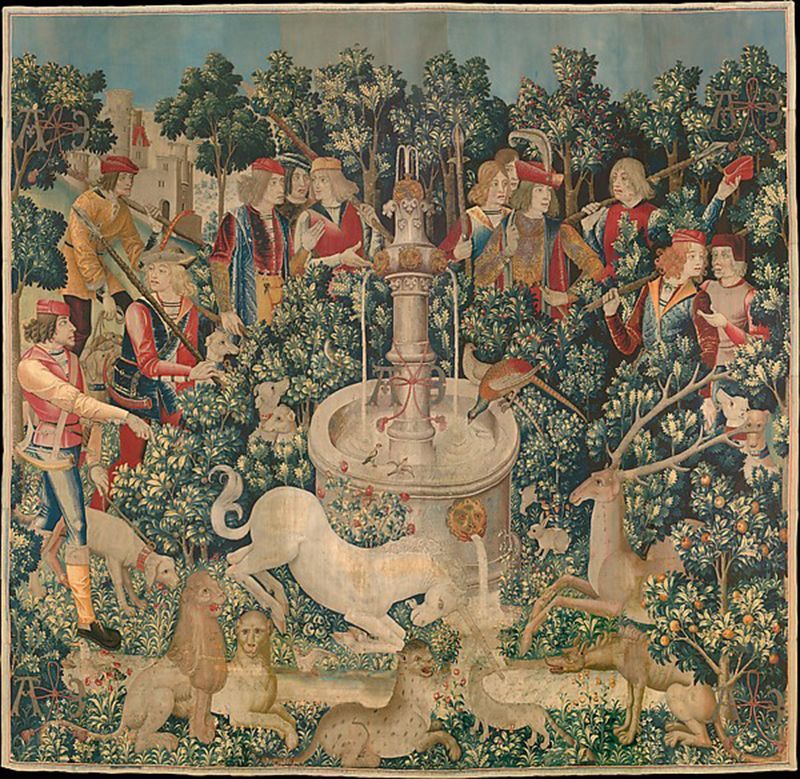

The Hunt of the Unicorn, a series of seven tapestries (collectively known as the Unicorn Tapestries), is one of the most famous works of art on display in the Cloisters. In 1922, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. purchased the set for one million US dollars, and hung six in his home before donating them to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1938. They now hang on the walls of gallery 17.

Secrets of Fort Tryon Park

For over 500 years, the Unicorn Tapestries have puzzled both art historians and scholars, who have attempted to decode the meaning of the pieces to no avail. The famous set, woven in wool, silk and metallic threads, depicts a group of noblemen in pursuit of a unicorn. The letters “A” and “E” can also be found in several places throughout the tapestries, but they have not been traced back to an origin.

The Cloisters is known for its stunning architecture. The museum building incorporates architectural elements from five Medieval monstaries and cloisters from Europe – Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Trie-sur-Baïse,Bonnefont-en-Comminges and Frovill. Between 1934 and 1939, the parts were disassembled and shipped to New York City, where they were reconstructed in Washington Heights under the guidance of architect Charles Collens.

Find refuge in 6 actual cloisters and monasteries in New York City.

Hops (Humulus lupulus) became a key ingredient to brew beer beginning in the fourteenth century in Europe. Prior to that time, brewers utilized a variety of different herbs, including alecost (Tanacetum balsamita), which was known to give off a minty aroma.The Trappist monasteries of Europe, for example, brew their own beer and export the product around the world. Today in the Cloisters, “medieval herbs” can be found in the Bonnefont garden in the Cloisters, though there isn’t a beer brewing operation.

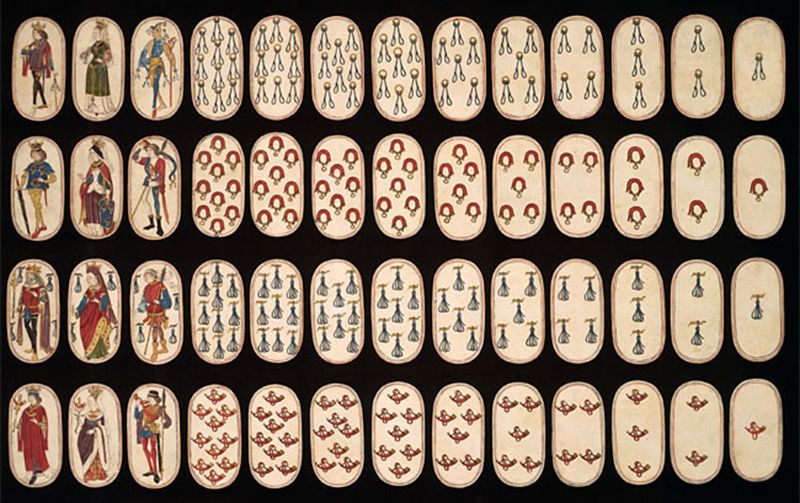

You can find the world’s only (known) deck of playing cards from the 15th century located inside gallery 13 of the Cloisters. The set is comprised of 52 cards, made from four layers of pasteboard, decorated using pen, ink, opaque paint and glazes. Like modern decks, it is comprised of four suits (hunting horns, dog collars, hound tethers, and game nooses). However, its condition suggest that they were rarely (or never) used.

If you dare come close to any of the treasured pieces in the Cloisters, a motion-detecting alarm on the ceiling will set off. According to a security guard, 99 percent of people who visit the museum trigger the security buzzers, inspiring this New York Times article. In fact, it happened so frequently that the alarms had to be adjusted to make them less sensitive and loud.

In 1917, after purchasing the Billings Estates along with other properties in the Fort Washington area, philanthropist John D. Rockefeller commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (the son of one of the designers of Central Park) and the Olmsted Brothers firm to create Fort Tryon Park. As part of the project, four acres of land was set aside to construct the Cloisters museum.

The institution features some pieces from Rockefeller’s own collection, but many medieval works come from a collection that once belonged to American sculptor George Grey Barnard. Although Barnard had already established his own medieval-art museum (the original Cloisters) in 1914 on Fort Washington Avenue, he was forced to sell his collection to the Metropolitan during a financial crisis.

The Cloisters’ gardens are maintained by a team of horticulturalists, many of whom are historians or researchers, who specialize in medieval gardening techniques. To set the context of the museum, three of the reconstructed cloisters encompass gardens that are planted according to information found in medieval treatises, poetry, garden documents and works of art, including the museum’s famous stained glass windows. Today, the green spaces provide a home to rare medieval species, as well as over 250 genera of plants.

Well-tended gardens, featuring a variety of plants, played an essential role for survival in fortified churches and abbeys. As such, it’s no surprise that The Cloisters is full of lush green space. Although a theory suggests that its original design was partly inspired by a fortified castle (Kennilworth castle), the cloisters were thought to be more suited to a chapel. The museum was consequently designed in the style of a fortified monastery.

Established on July 1, 2008, The Medieval Garden Enclosed serves as resource for visitors to learn about the gardens at The Cloisters. The blog posts explore topics dealing with the roles and uses of specific plants in the Middle Ages. Moreover, a newer blog, In Season, includes information about events and other on-going activities at The Cloisters. Weekly blogs also focus on medieval plants, conservation projects and research on the museum’s varied collection.

Secrets of Fort Tryon Park

Next, check out The Top 10 Secrets of NYC’s Fort Tryon Park and Find Refuge in 6 of NYC’s Monasteries.

Subscribe to our newsletter