New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

When the demolition of nearly 200-year-old 355 Grand Street, a historical Federal-style row house on the Lower East Side, is complete this week, work on new six-story condos building will begin. While 355 Grand Street is no Old Penn Station, it does have some serious street cred and fascinating New York City history. To give this unsung long-time survivor a proper sendoff, we took a deep dive into various historical sources including vintage newspapers, census reports, and personal accounts. Each fact found is a small portal into New York City’s greater narrative.

Downtown writer Joe Clarke put it this way, “355 Grand exemplified (stood out, quite frankly) as a real example of what the neighborhood felt like 100 years ago, as (very real to me) literary characters from David Levinsky to the characters from Ragtime, The Alienist and countless others traipsed through. You could stand looking at that corner (across the street from the school attended by Walter Matthau, et al) and know that all these millions of people, fictitious and real, stood there for over 100 years and saw the exact thing as you. You could *feel* the neighborhood by looking at that building. Its disappearance will erase that feeling forever.”

Image via Google Maps

Before eviction notices, the building housed a popular local Woodstock-era themed café, called Flowers, and on the Essex Street side of the building, a pizzeria called Vic’s. In late 2015, both businesses were kicked out, so Joseph Pizzo, who picked the building up for peanuts back in 1976 could sell the now-hot real estate site. In 2015, local website The Lo-Down reported that Jenny Lai of Brooklyn’s Interboro Properties purchased the site for $4 million, after Pizzo’s Fizzo Realty asked for $4.5 million.

Image via Google Maps

Let’s go back to the 1820s when part of the current building was built. Like many old buildings, it’s unclear exactly what year construction began on the site, but old papers mention that a man named James Shea owned the property in 1826.

In 1845, the two-story building caught on fire from the gas pipe in the window. Fortunately, this incident was ten years after the Great Fire of 1835, when downtown New York was set ablaze. By then though, New York was blessed with a newly installed water system of over 40 stone tunnels that led water from the Croton River in Westchester directly to Manhattan. (This then “modern marvel” was constructed between 1837 and 1842.) Croton water quickly curbed the fire, and no flames jumped to other Grand Street buildings.

Demolition as of December 1st, 2016

A man named Win Baker who lived at 355 Grand Street was drafted in 1863 for the Civil War. Was he part of the New York City Draft riots protesting against rich men uptown who bought their way out? There was also a gin mill kept there by a dubious character named George Melvin in 1870. Scant info is available but a gin mill is juicy enough for a mention.

In 1882, advertisements in several papers suggested New Yorkers head to 355 Grand for a chance to buy a gently used “one top side bar road wagon.” It had only been run a few times, and it originally cost $275, but the owner was willing to let it go for $95.

A young woman named Ellen Cheesman died at 355 Grand at 21 years of age in 1884; she was the wife of a Henry Cheesman. Cheesman is an unusual name, and unless there were two Henry Cheesmans, the new widower was a druggist who had formerly lived in Brooklyn Heights on Pierrepont Street.

The tall cast-iron building is 347 Grand Street, where The Grand was once located, with an abandoned remnant of old New York at the corner

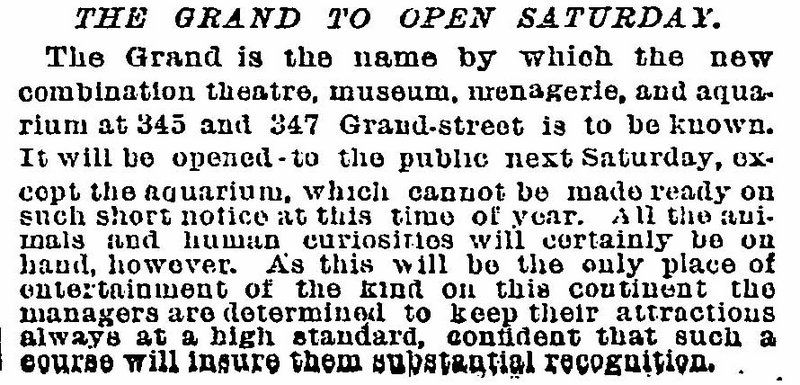

According to several 1937 obituaries, around 1888 a very New Yorky character named George Peck—a Londoner who managed the world tour of Mr. and Mrs. Thumb for P.T. Barnum—opened an establishment at 355 Grand called Peck and Fursman, with five floors of entertainment, filled with curiosities, side shows, and a circus. This activity at 355 Grand sounded strange to us based on the other information we found, so we located an ad from opening year. Yes, there were mermaids, dwarfs, and wild beasts galore on the block, and newly remarried Mrs. General Tom Thumb in residence, not to mention a “Hindoo” snake charmer. Yes, there were stage performances from 10 am to 10 pm, with an admission of only 10 cents for everything. But sadly even the New York Times got it all wrong. The GRAND, a museum, menagerie and model theater, was actually located a few doors down at 345 and 347 Grand Street.

From the New York Times, December 2nd, 1888

Less thrilling: According to an 1890 Italian ad in Eco D’Italia, there was a fruit stand parked outside the building, doing good business for 25 years, up for sale. And then in 1891 a C. Knight and his wife transferred the property to Sarah A. Knight for $7,500. Was Sarah their daughter?

In 1892, there was a clothing store in the base of 355 Grand owned by Adolph Gluck. That year, Gluck was the target of an eight-year-old rascal named Arthur Goldberg from Russia. Goldberg, who lived over at 183 Chambers Street, was caught red-handed poaching a child’s suit. Such hubris must be punished! At the Essex Market Police Court, the tyke was held with a $1000 bond, and handed over to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Adolph Gluck was still open for business in 1894, when he placed an ad seeking an experienced German salesman for cloaks and suits. He is still there in 1899, looking for an experienced bright young salesman.

In 1901, alterations were filed in municipal offices by Sarah A. Knight (who you’ll recall we last saw in 1891); she was converting her building to a two-story brick store with a photograph gallery. Architect John G. Pfuhler, of 157 East Fourth Street, was hired at a cost of $150.

In 1901, the owner was Charles Meyerson. There’s very little more on Mr. Meyerson or what happened to Sarah A. Knight of 1901. The answers are lost to history.

By 1903, an auctioneer named Michael Cohen sold Japanese goods and bric-a-brac from 355 Grand, as well as another auctioneer named H. Wasserman. They took turns advertising in papers. Turns out they were business partners, for in 1903 Wasserman and Cohen also managed a Hotel Rosenberg in the spa village of Sharon Springs, New York, 50 miles north of Albany. Although Sharon Springs was once frequented by Vanderbilts and other boldface Protestants, the la-di-da set mortified by the gaucheries of the Jews moved their kind to Saratoga Springs where even the most uppercrust “Gentleman Jew” from a proper German family was discriminated against. The Jewish upwardly mobile crowd decided to reclaim Sharon Springs as their own. (The old Rosenberg Hotel is now part of the Roseboro Hotel).

Also on Grand Street, just a block away is another old New York City building with a vintage sign. The store still sells hosiery.

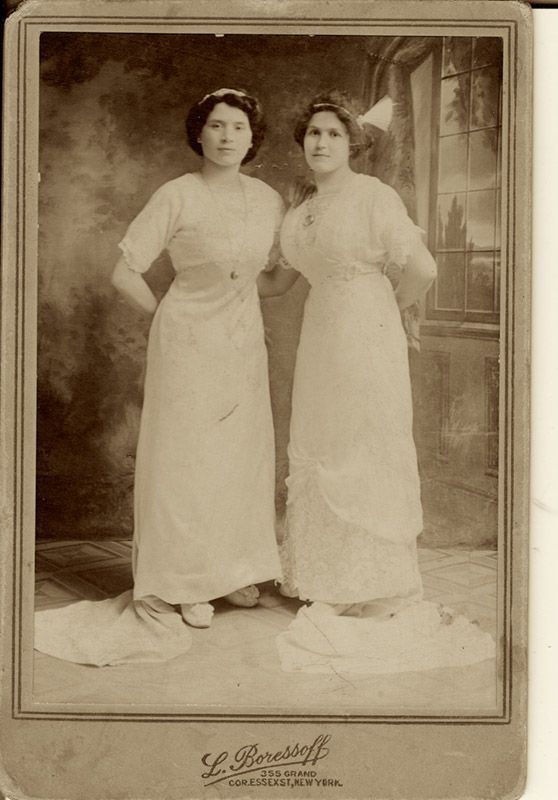

In 1912 there was a 41-year-old photographer on the premises named Louis Boressoff, who according to the 1910 census born in about 1869, and married to a 29-year-old named Clara. Here’s a photo taken by him.

Untapped Cities reader Alyce C. sent us the above photo. She writes: “My maternal Grandmother, Rebecca (Beckie) Rosen, lived on Henry Street after she arrived in the US in 1907. She’s on the left, with a woman I can’t identify, photographed by L. Boressoff at 355 Grand. My best guess is 1908-1911.”

When the census taker came knocking, he had three kids, Annie, 16; Sally, 4, (that was a census typo, Sally was a boy named Lollie – as a later census picked up) and Jacob “Jackie” 2 (who died in 1930). Our guess is that Annie was from a first marriage and that Louis was a widower who’d remarried. Back then the census was taken every five years, and by the 1915 census, another child name Beatrice was along, already 4. To be a little OCD about the Boressoffs, another son was born to Louis and Clara just after the 1915 Census, July 16, 1915, who died in 1977.

Also, for the historical record, the Boressoffs had a white Austrian servant named Mary Jacklin living with them. Louis died in 1928, and was buried in Glendale, Queens.

Another fire hit 355 Grand in 1917, and a man named Jacob Gilman took a $500 loss. A truck driver named James Marcus lived there in 1921, and one day jammed into 22 passengers on the Belt Line when he was driving his truck from Essex into East Broadway. The 22 passengers all lived, but it made a good story on a slow news day.

Flowers Cafe is one of the shop interiors captured on Google Street view in 2010, so we will have the interiors of 355 Grand Street available for posterity

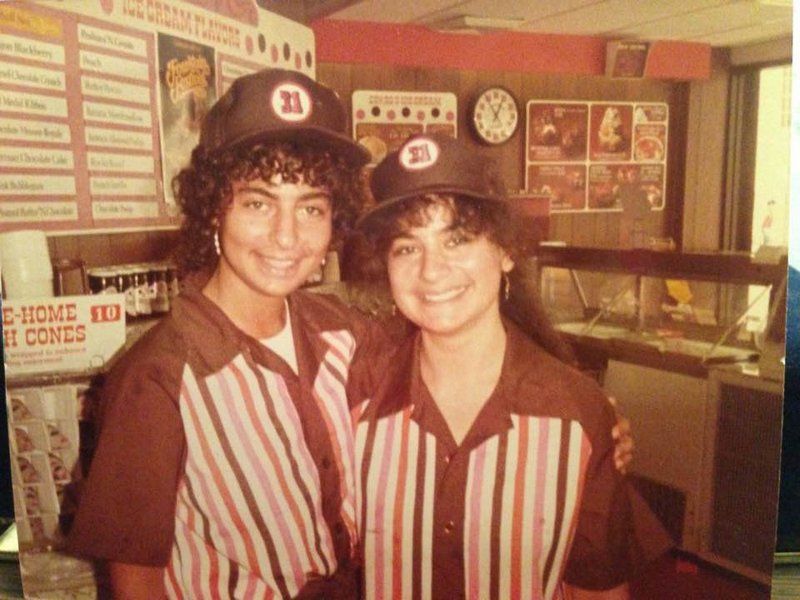

In a 1931 Manhattan directory, a Herman Fogelman is listed as a resident. The 40s and 50s are a big gap history-wise as far as 355 Grand goes, but we tracked down Hinde Nessanbaum, who worked in the building in the 1980s when it housed a Baskin-Robbins where she would occasionally slip friends a second scoop gratis. Hinde loves New York history too and by phone helped with some details from the late 1960’s. Her cousin Ronnie Fein owned (“or maybe just worked in”) Showcase, the beauty parlor that occupied the Grand Street space where Flowers Café was, not to be confused with the Jodali salon that existed next door a few years later. “I clearly remember the strong hairspray smell of Showcase, the big old hair dryers, and the manicure cart they wheeled around to polish the neighborhood ladies as their permanents dried.”

View looking outside from Flowers Cafe towards the Seward Park Cooperative

Hinde continued, “In the 1970’s the storefront on Grand Street had an old school New York City pizza place called Grandola. My cousin Ronnie and his business partner Joe definitely owned that joint, until they moved around the corner to the smaller store on the Essex Street side of the building, called Joe’s Pizza.” She also recalled that there was a Vic who worked for Joe, and when Joe retired, Vic renamed the pizzeria after himself. Hinde thinks the Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlor she worked in opened around 1982-83: “I was in the first team of hires which included a true Lower East Side melting pot of high school kids: Puerto Ricans, Jews, Dominicans, African-Americans, Chinese. I was a high school sophomore at Stuyvesant, and I worked side by side with kids from all over, from Seward Park High School, Murray Bergtraum and downtown Brooklyn. I remember a couple of the kids competed in break dance and hip hop competitions in the city when that was big in the 80s; they’d spin on their heads on broken down Baskin-Robbins cardboard cartons showing us their moves.

1980s photo from Baskin-Robbins with Sisters Erica Cohen and Hinde Nessenbaum

Others spent hours at Seward Park Library studying for the SATs and PSATs before and after their shifts. I learned a lot about people and diversity working in that place, such different cultures and lives, but we all spoke ice cream, that was common ground. I don’t remember the owner’s name but he had a second franchise on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights. His young son’s name was Zachary and I remember one of the wise-guy kids I worked with teasing him, ‘Want a Daquiri, Zachary?’ Daquiri was a flavor back then, not sure if it still is. But I thought that was clever.”

Also, Hinde pleads the fifth as to whether a free scoop or two ever went my way. “I will however admit to throwing a burgundy cherry to my Grandma Jennie every once in awhile.”

The last day of business for Flowers Café was September 18, 2015. This Untapped Cities’ author’s now 14-year-old daughter Violet O’Leary, who only remembers Flowers Café, was very distraught that the place was closing. She decided she had to document herself having a late afternoon ice cream cone. It was 5 o’clock when we had to leave. She was without a doubt the last customer at any 355 Grand establishment.

Next, check out the archeological finds beneath 50 Bowery.

Subscribe to our newsletter