♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Photo by New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection via Library of Congress

New York City is one of the most publicized and written about places in the world. Between New York City’s relatively short history (compared to historic European cities) and the sheer quantity of literature written, it may seem as though every nook and cranny of the city has been discussed. However, the city still has its fair share of mysteries that are yet to be solved. Some of them pertain to murders and disappearances while others came about during the city’s ever changing urban landscape.

Here are 10 New York City’s unsolved mysteries.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

On December 12, 1910, a wealthy socialite stepped out onto the sunny streets of Fifth Avenue–only to disappear later, never to be seen again. Dorothy Arnold, the daughter of a wealthy cosmetics and perfumer left her family home on Fifth Avenue around noon. After running a few errands, she ran into a friend outside a bookstore at 2 p.m with whom she had a short conversation; that was the last time anyone saw of her.

What followed was countless man-hours by the police and family, tracking her last moves on the final day of her vanishing, and a frenzy of attention by newspapers around the country. Newspapers followed the case and the seemingly endless bevy of vague leads and tips day-by-day. And yet, despite the immense publicity that the case engendered and the prolonged investigation which lasted for years, no concrete theory was ever established to justify her disappearance.

Dorothy’s disappearance was noticed a few hours later when she was absent from dinner. Yet, Being the daughter of an affluent family, and thereby hoping to avoid unfavorable publicity, the family kept her disappearance from the police and opted to hire their own investigator. After six weeks however, despondent and desperate, they finally went to the police for help.

The entailing police investigation was thorough, with her activities leading up to her disappearance being retraced and scrutinized. Dorothy Arnold lived a busy social life that included many potential suitors–many of whom were taken in for questioning, all to no avail. Given the Arnold family’s social status the case elicited international attention and soon leads came pouring in from all around the country and globe–for years. And yet, none of them amounted to anything.

In early 1911, a shop owner claimed that he’d spotted Dorothy Arnold buying men’s cloths for a disguise and inquiring about a steamer fare. Reports came in of her having been spotted in Italy, and later in Chile, and a flurry of sightings in other countries and U.S cities–all of which amounted to nothing.

Perhaps one of the more feasible leads was that of a prisoner in Rhode Island who claimed he’d been hired to help bury a wealthy woman in a cellar in December 1910, a claim that never panned out either. Her father though, after years of hoping against hope, came to believe that she’d been kidnapped and murdered, a belief that he held onto until his death.

After both of Arnold’s parents died, the family lawyer went public with his own theory: Dorothy had killed herself because of her failure as an aspiring writer. Yet, the lack of discovery of a body puts a major dent in that theory as well as the others.

While this is a story that is unknown to the typical New Yorker, at the time of investigation the case was known across the country, and was covered by all–from the small-town papers to the major metro editions. As the Pittsburgh Press later opined, “It was the really great search of the age, and one that did much to develop modern newspaper police coverage.”

On the night of October 29, 1964, two Miami beach boys crept into the grounds of the American Museum of Natural History while a spotter drove a Cadillac around the museum block. The two men made their way into the J.P. Morgan Hall of Gems and Minerals and managed to get away with 24 priceless (and remarkably uninsured) gems, including the Star of India (the world’s largest sapphire), the Star of India (the world’s largest black sapphire), and the De Long Star Ruby, considered the world’s most perfect ruby.

The theft of the gems, which had an equivalent worth of $3 million today, severely exposed the lax security at the museum. Much to the geology curator’s dismay, it was revealed that the display-case burglar alarm had been dead for months. Moreover, the tops of all the gem halls’ 19 exterior windows were left open two inches overnight for ventilation, and none of them had burglar alarms.

The thieves, along with another accomplice were swiftly arrested due to their own indiscretion after the heist. The jewels, however proved to be more elusive. While the the Star of India, the Midnight Star, and the De Long Star Ruby were all found, only 10 of the 24 stolen jewels have to this day been recovered.

Photo by New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection via Library of Congress

Long before the horrific incidents that occurred on 9/11, another bomb rocked the heart of the city–this time in the form of a horse-drawn wagon. On September 16, 1920 a wagon loaded with 500 pounds of small iron weights and dynamites exploded in front of 23 Wall Street. The corner building at the time was the headquarters of J.P Morgan & Co., the nation’s most powerful bank.

The explosion instantly killed thirty people–and one horse; another eight people died from sustained injuries; hundreds were injured either from the shrapnel or by the jagged glass that rained down from the building windows. In fact the blast was so powerful that according to a bystander, a trolley carrying passengers two blocks away was “thrown from the tracks from the shock”.

No group or individual claimed responsibility for the attack, leading many to insinuate the communists. However, in their haste to reopen the stock market the next day, city officials inadvertently destroyed invaluable evidence that could have been conducive to identifying the perpetrators. While the three-year-long investigation that followed was fruitless, a 1944 FBI revisit of the case concluded that Italian anarchists were responsible for the plot. However, even this has never been substantiated. To this day scars of the bombing can be found on the limestone on 23 Wall Street.

Arnold Rothstein is a legendary name in the gangster world; he is credited with transforming organized crime into a massive business that pervaded into the lives of everyday Americans. From a young age Rothstein was talented with numbers, an aptitude that paid dividend in running a criminal business that included bootlegging, running speakeasies and brothels, and waiving the political powers in his favor by filling politics with his gangsters. Rothstein was even responsible for match-fixing at the 1919 World Series, where he paid White Sox players $10,000 to intentionally tank the game – the meeting where this was decided took place at The Ansonia Hotel.

Also the consummate poker player, Rothstein’s luck finally ran out in 1928 when he encountered an unprecedented losing streak that left him with $320,000 in debt. Rothstein refused to pay the money, however, claiming that the game had been rigged. Two months later, in another poker game, he was shot in the stomach as he entered room 349 at the Park Sheraton Hotel (now Park Central). Rothstein managed to catch a fleeting glimpse of his assailant as he dragged himself out of the Midtown establishment through the service elevator. However, even on his deathbed two days later he refused to give the name of his killer when questioned by the police, staying true to the gangster code of silence.

The police tried McManus (the poker game organizer whom Rothstein owed money to), however he was ultimately acquitted, leaving the murder unsolved.

On March 9, 1929 Polish immigrant Isidor Fink was murdered in his New York City laundry in what is a quintessential case of a locked-room mystery. Shortly after arriving home the neighbors heard terrible screams. The police arrived on the scene only to find the door locked from the inside and the windows nailed shut from the inside as well. With the windows also being too small to climb through, the police gained access to the apartment by means of a small child who was lifted through the transom.

What the police found was a baffling scene that to this day defies any logic. Fink was found dead with three gunshot wounds to his chest and wrist. No weapons were recovered from his apartment, while the only fingerprints found were his own. Murder was ruled out by the fact the murderer would not have been able to lock the door from the inside; moreover no murder weapon was recovered. However, suicide also seemed impossible given the lack of murder weapon. Also, its unclear why a suicidal Fink would have shot his wrist first. The scenario of a shot having come in through the window was also ruled out due to the singed skin around the wound. And while the murder could have potentially locked the door from the outside using a string, the time frame for escape would have been very small, making it implausible. Also, the necessity of locking the door is questionable.

All these inexplicable facts make this a case that had NYPD Commissioner of the time, Edward Mulrooney regard as, “unsolvable”.

In the late 1870’s about two million cows were being herded through the bustling streets of New York City. A rumored solution that still persists is a series of underground tunnels to transport cows from the dock to the slaughterhouse. While there are no sketches or pictures of these tunnels, Nicola Twiley from Edible Geography was able to find some evidence suggesting the existence of these cow tunnels.

In an archaeological documentary study in 2004, the transportation engineering firm Parsons Brinckerhoff identified the location of two cow tunnels in the Hudson Yards area. However, the source of their conclusion is the book, New York in the Nineteeth Century rather than new archaeological evidence.

While the office of Sanborn maps of New York City has no evidence of the tunnel’s existence, during the reconstruction of Route 9A (West Side Highway), there was a permit for a tunnel of such sorts at West 38th Street. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has no official record of the tunnel’s existence, however no archaeological work has been done either, leaving the existence of the tunnels a persisting mystery.

Image via Library of Congress

The Bogardus Building once stood in downtown New York City in the Washington Market area. While the area was undergoing urban renewal in the 1960s, the decision was made by the Landmarks Preservation Commission to save the Bogardus Building and use its elements to create a new building nearby. Ergo, the facade of the building was taken down and stored in a vacant lot.

On June 25, 1974, the building contractor discovered three men loading large pieces of the building onto a truck, much to the dismay of Beverly Spatt, the chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, who reportedly ran into the City Hall press room yelling, “Someone has stolen one of my buildings.”

The truck was traced to a Bronx junkyard, where two-thirds of the facade had been already sold as scrap. The salvaged panels of the building were taken back, this time to a secret location in a city-owned building, in order to be incorporated in a building at the South Street Seaport.

The architect went to the building to measure the panels in June of 1977. To everyone’s shock, the storage unit was empty – the building had been stolen yet again. In 2015, the Museum of the City of New York exhibited a single spandrel panel from the Bogardus Building that still remains. A building at South Street Seaport, on Front Street and Fulton Street, was constructed as a replica of the Bogardus Building, but none of the architectural elements are original.

Much is known about the cornerstone of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, especially after the five-year, $175 million renovation of what is deemed as the nation’s largest Roman Catholic Gothic sanctuary. It is known that the cornerstone was hand-cut by a 22-year-old Irish immigrant, and that it was laid on August 15, 1858, the Feast of Assumptions, by John Hughes.

Yet there is a major gap in our knowledge about the cornerstone. No one knows where it is and when it went missing. While it is was laid at the corner of 50th Street and Fifth Avenue, the cornerstone is not located in any of the plans. One theory states that the cornerstone might have been dislodged or moved later during construction of the Lady Chapel at the cathedral’s eastern end.

On a prophetic note, the Archbishop of the time, John Hughes, seemed to believe that unlike other time capsules, this one would never be discovered, predicting that “in all probability, [the cornerstone] will never be disturbed by human agency.” 156 years later, he stands correct.

Image via nywf64.com

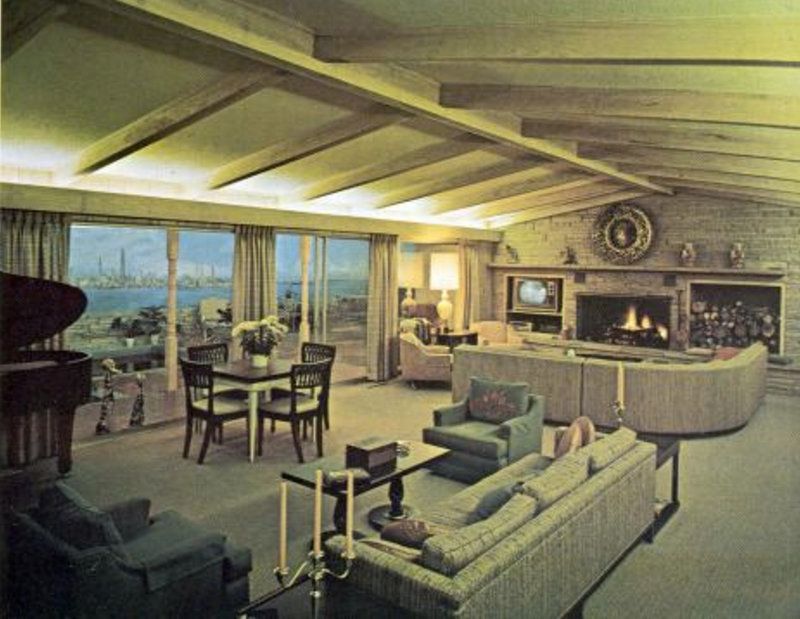

One of the more famous displays at the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows Corona Park was an Underground Home designed in in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Fifteen feet below ground, a concrete shell enclosed a 12,000-square-foot home with ten rooms – this was no simple bomb shelter. Designed by Texas builderJay Swazye, the bunker included a Steinway piano in the living room, an air filtering system, adjustable lighting to simulate time of day and season, and a fake garden.. Although the majority of the temporary structures from the fair were meant to be torn down, a theory posits that the Underground Home is still there beneath the park. As Narratively writes, “Some…believe that Swayze, wanting to avoid high demolition costs, removed furnishings from the Underground Home but left its shell intact, hidden beneath several feet of dirt.”

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

For years, intrepid explorers looking to get a glimpse of the world’s first underground transit tunnel, built in 1844, could sign up for a tour with Bob Diamond, one of Brooklyn’s most quixotic self-made urban archeologists. After dodging traffic and waiting for the lights to change, guests would descend one by one through a manhole removed off the middle of Court Street and down a ladder. They’d emerge into a cavernous space over 2,500 feet long.

Diamond discovered the Atlantic Avenue tunnel in 1980, a remnant of a subterranean portion of the Long Island Railroad that connected New York to Boston. This portion of the line existed before the London tube was dug in 1863.The Atlantic Avenue tunnel was placed below grade to prevent deadly street level accidents between pedestrians and the trains in the already bustling neighborhood. The tunnel was sealed off in 1861, following a new policy that prevented steam locomotives from running in Brooklyn.

Diamond did the excavation himself and has been fighting for the last thirty years to use the tunnel to revive trolley transportation and create a museum. A series of controversies and lawsuits, worth a book in itself, halted Diamond’s progress and the tunnel was closed off to tours in 2010.

Diamond believes that there is an 1836 locomotive, buried in the tunnel and an engineering firm confirmed through an electromagnetic imaging scan that there was a large metallic object, about the dimensions of the lost train behind the wall. Diamond himself has lost access to the tunnel as well and most New Yorkers are skeptical that this portion of the tunnel will ever be opened to the public again.

Next, check out 5 notorious NYC crime scenes.

Subscribe to our newsletter