After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

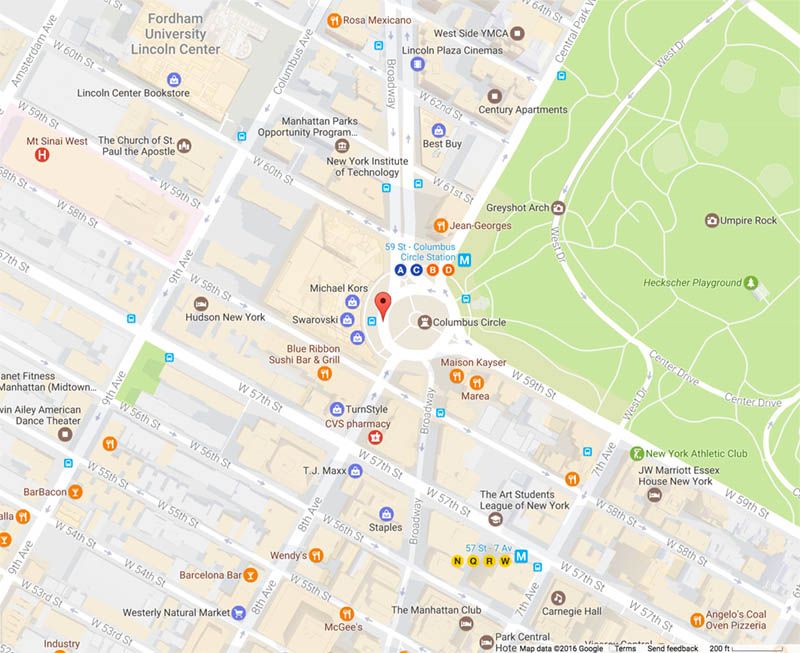

Like Times Square, Union Square and other bustling intersections found throughout New York City, Columbus Circle is full of zooming cars and quick-footed pedestrians. As one of the more heavily trafficked areas in Manhattan, it’s a noteworthy tourist attraction and busy commercial center, located at the southwest corner of Central Park. There are multiple places worth visiting nearby: the Time Warner Center, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Shops at Columbus Circle, and the newly opened subterranean mall, TurnStyle. With such a wide array of retail shops and stunning landmarks, the traffic circle is much more than a channel to ferry cars and the occasional horse-pulled carriage through NYC’s rush hour gridlock.

Just like the Grand Army Plaza – the only corner of Central Park that’s officially included in its 843-acre landscape – Columbus Circle was part of the original vision for what would eventually become the most visited urban park in the United States (and one of the most filmed locations in the world). Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and designer Calvert Vaux, who designed Central Park, envisioned a “grand circle” at the 8th Avenue entrance. Just like the traffic circle around the Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile in Paris, the entryway was intended to provide an open view of the park as people approached to visit.

One of the most recognizable features of Columbus Circle, the statue of Christoper Columbus was unveiled on October 12, 1892 in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of his arrival in the New World. Created by sculptor Gaetano Russo and constructed using funds raised by Il Progresso (a New York City-based Italian-language newspaper), the monument depicts Columbus standing assuredly on top of a 70-foot granite pedestal, where an angle sits inspecting a globe. Bronze reliefs of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María can also be found, decorating the column.

In light of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ expedition, the monument was restored in 1992. In 2012, artist Tatzu Nishi also situated the statue inside a fully furnished living room as part of his Discovering Columbus exhibit. Visitors had to ascend six flight of stairs to reach the fictional space, where they found the statue posing on a coffee table; to add to the authenticity of the experience, Nishi fitted the room with furniture, including tables, chairs, a flat-screen television, and even custom-designed wallpaper.

See photos here.

Image via Google Maps

In a previous article, we examined the logic behind the selection process for Manhattan’s major cross streets. Here is the relevant passage from the 1807 plan of John Randell dealing with the topic:

Those passages which run at right angles to the avenues are termed streets, and are numbered consecutively from one to one hundred and fifty-five. The northerly side of number one begins at the southern end of Avenue B and terminates in the Bower lane; number one hundred and fifty-five runs from Bussing’s Point to Hudson river, and is the most northern of those which is was thought at all needful to lay out as part of the city of New York, excepting the Tenth avenue, which is continued to Harlem river and strikes it near Kingsbridge. These streets are all sixty feet wide except fifteen, which are one hundred feet wide, viz.: Numbers fourteen, twenty-three, thirty-four, forty-two, fifty-seven, seventy-two, seventy-nine, eighty-six, ninety-six, one hundred and six, one hundred and sixteen, one hundred and twenty-five, one hundred and thirty-five, one hundred and forty-five, and one hundred and fifty-five–the block or space between them being in general about two hundred feet.

Of these major cross streets, Columbus Circle is worthy of a special foot note due to its central location. It’s lined with shops and situated a relatively short walking distance away from many of New York City’s major attractions, including Times Square and Rockefeller Center. It comes as no surprise that it’s regarded as the geographic center of the city. This means all official distances from New York City are measured from this point. As noted in NYC-Grid.com, London is 3478 miles away from New York City, which really means it’s 3478 miles away from Columbus Circle.

Columbus Circle circa 1913. Image via Library of Congress.

The tall building in this photograph held Manufacturer’s Trust and Gotham Bank but was later demolished to make way for the New York Coliseum. 59th Street was then eliminated between Broadway and Columbus Avenue, a street pattern that continues to this day.

Just adjacent and around Columbus Circle was once a bustling, diverse neighborhood known as San Juan Hill, that was targeted by Robert Moses and the the New York City Housing Authority for urban renewal. San Juan Hill was the city’s destination for jazz. The agency described it as “the worst slum section in the City of New York” during the 1940s, in order to set the stage for the mass demolition of – an urban policy that often racially targets specific populations that is generally denounced today in New York City (though continues sadly all around the world). Before the clearing, the built fabric of the area did get captured for posterity on the silver screen in West Side Story. The main anchoring institution built atop the lost San Juan Hill neighborhood is Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, along with Amsterdam Houses (above).

See vintage photos of Columbus Circle’s transformation over the years.

The above photo, taken by Margaret Bourke-White, was originally included in our vintage photos of Columbus Circle post. While it was captioned in LIFE Magazine as “Columbus Circle, New York City, photographed from a helicopter, 1952,” several readers pointed out that the image had been mislabeled. In light of the discovery, we decided to do some investigation by reaching out to Getty Images. Joelle Sedlmeyer, the research editor, responded with the following:

We cannot confirm it is Columbus Circle. LIFE.com says it is and that is all the information I have. I wish we had more info but the photographers did not write down their shoot subjects. This shoot was labeled- NYC aerials.

We have reason to believe the image was taken in Philadelphia. Using the equestrian statue as a starting point, Benjamin Waldman, the Untapped Cities History Editor, was able to track down the Washington Monument in Philadelphia, which appeared to have the same fountain, octagonal base and four subsidiary sculptures. The misattribution might have been due to the words “EAST RIVER DRIVE,” which can be seen in the photo, painted on the road on the top of the traffic circle. Formerly known as East River Drive, Kelly Drive in Philadelphia was renamed in the 1980s for Councilman John B. Kelly, Jr. However, East River Drive (now FDR Drive) existed in New York City, too!

Located at the Merchants’ Gate of Central Park, visitors can find the USS Maine National Monument, designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle and sculpted by Attilio Piccirill and Charles Keck. Built in 1913, the statue honors the 260 American sailors who tragically died on February 15th, 1898 after the battleship exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba. While the cause of the incident remains a mystery, New York City newspapers were quick to blame the Spanish for the supposed “attack.” The mysterious exploration eventually triggered the Spanish-American War, which would last eight months.

The idea for the public memorial was later put forth by newspaper publisher Randolph Hearst. It features a limestone base sculpted in the shape of a ship’s bow and surrounded by figures representing Justice, Peace, Victory, Courage and Fortitude. On the top of the pylon, sits a large gilded bronze figure of Columbia Triumphant (Liberty Triumphant) leading a seashell chariot pulled by three seahorses, which are reportedly cast from metal recovered from the guns of the ship. In 1995, the Central Park Conservancy restored the memorial by cleaning, pigeon-proofing and re-gilding the sculpture; missing parts were also carved and fitted into the monument.

Audrey Munson with photographer Arnold Genthe’s cat Buzzer, 1915. Image via Wikipedia

You’ve come across Audrey Munson, America’s first supermodel, on multiple occasions. She’s the face of New York City, memorialized in statues that decorate various institutions and tourist attractions throughout the city. Among a number of places, you’ll find her sitting on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building downtown, on the facade of the New York Public Library at 42nd Street and as Columbia Triumphant for the USS Maine Monument in Columbus Circle. Known by the nickname, “Miss Manhattan,” Munson made a living by posing as a model for photographers, painters and sculptors in the early 1900s. Unfortunately for the young model and artist, scandals began to follow her, eventually causing her mental breakdown. At 39-years-old, she was committed to a mental institution, where she stayed until her death at the age of 104.

Today, “Bloomingdale” refers to the section of land from 96th to 110th Streets between Central Park and the Hudson River. There, you will find eponymous institutions like Bloomingdale School (P.S. 145), the Bloomingdale Public Library and the Bloomingdale School of Music. The name, however, once encompassed a much larger portion of city, including the entire west side of Manhattan north of Great Kill (a creek near what is now 42nd St.) to present-day Washington Heights. In fact, Bloomingdale Road, which was constructed around 1708, originally started at the site of Madison Square, and ran all the way up to 115th St. and Riverside Drive (and later to 147th St.).

Thus, when the city’s street plan was adopted in 1811, it included a section of land for Bloomingdale Square. The park would have spanned 53rd to 57th Streets between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. The original proposal, however, was scrapped in 1857 when Central Park was constructed. Bloomingdale Road north of 59th Street was also closed and replaced by the present Broadway in 1868.

Pabst Grand Circle Hotel in Columbus Circle on far left c. 1907. Photo from Library of Congress.

Columbus Circle was once filled with Victorian-style buildings, including the Pabst Grand Circle Hotel and the Majestic Theatre, built for the Pabst Brewing Company in 1903. In 1954, the complex was demolished and later replaced by the New York Coliseum, an exhibition hall and convention center that stood at the site from the 1956 to 2000. During its lifetime, it hosted a variety of events, such as the New York International Auto Show, the National Photographic Show, and the Fifth International Philatelic Exhibition. By the 1990s, however, the area had become extremely run down (partially depicted in this photograph), and in 2000, the Coliseum was cleared to make room for the present day Time Warner Center.

When the Christopher Columbus monument was completed in 1913, the traffic circle surrounded the statue in extreme proximity to its base. The hazardous design led architecture critic Paul Goldberger to refer to Columbus Circle as “a chaotic jumble of streets that can be crossed in about 50 different ways – all of them wrong.”

In an effort to fix the issue, a two-year renovation effort in 2005 gave rise to an island oasis that currently surrounds the monument. It is fitted with benches, beautiful landscaping and fountains, which are designed for visual and auditory appeal. According to The New York Times, the sound of the water can actually sound like “a swollen river, a rushing brook, a driving rain or a gentle shower.”

Next, check out Columbus Circle in NYC Over the Years Since the 1900s, and check out this guide Christopher Columbus Monuments Across NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter