Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

Washington D.C is typically the burial ground of America’s historic figures and great generals. Countless figures have been buried in the grounds of Arlington Cemetery with numerous monuments erected to honor American heroes. Interestingly, General Ulysses S. Grant, the great Civil War general and 18th President of the United States, is buried here in New York City.

Located on the northern end of Riverside Park adjacent to Columbia University, is the General Grant National Memorial, the final resting place of Ulysses S. Grant. The great general died of a throat cancer in 1885 in Wilton, New York, at the age of 63. The incumbent mayor at the time, William Russell Grace wrote a letter to New Yorkers to garner support for a national monument in Grant’s honor. The prospect of having General Grant’s memorial in New York City drew public support. The preliminary meeting was attended by 85 New Yorkers and an organization by the name of Grant Monument Association (GMA) was formed.

There was strong opposition from Washington D.C however, voicing that the monument should be in D.C, along with the other great monuments and tributes to American heroes. Mayor Grace calmed the controversy by releasing a statement by Mrs. Grant in which she stated, “Riverside was selected by myself and my family as the burial place of my husband, General Grant. First, because I believed New York was his preference. Second it is near the residence that I hope to occupy as long as I live, and where I will be able to visit his resting place often.”

Aside from hurdles in the form of opposition to the monument’s location, the GMA was confronted with funding issues, such that it was not until February of 1888 that a design competition was announced. After two competitions, the design of John Hemenway Duncan, an architect who had had previous experience designing structures to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the US Revolutionary War, was chosen for the tomb. Duncan cited his design objectives, saying, “…to produce a monumental structure that should be unmistakably a tomb of a military character.”

By 1890, as the GMA was finalizing their design, the debate over the tomb’s location was rekindled in Congress, with Senator Hale introducing a legislation that would move the sarcophagus to Washington D.C.. While the bill did not pass, it reopened debates over the location of the monument. These debates prolonged past even the groundbreaking ceremony, until they were finally put to rest in June 1891, when the decision to have the monument in New York City was finalized.

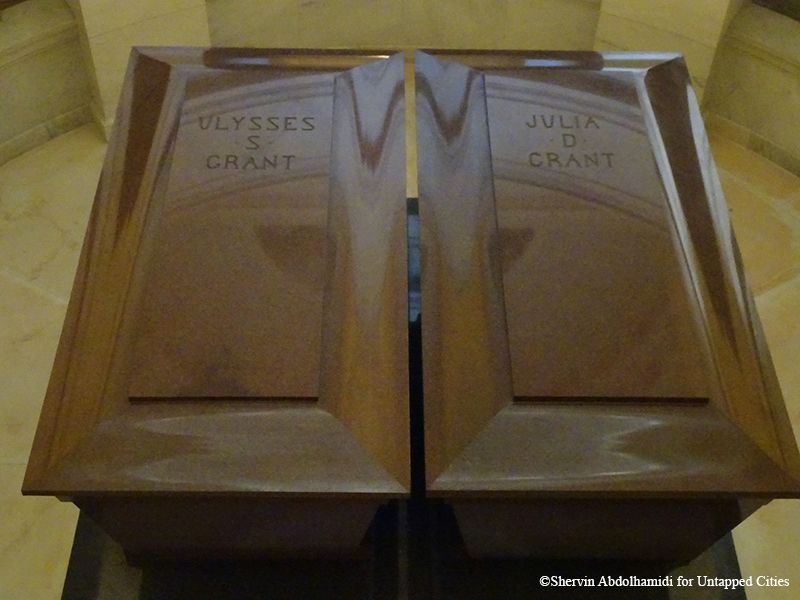

The tomb was finally inaugurated on April 27, 1897, on the 75th anniversary ceremony of Grant’s birth and six years after construction had started. On April 17th, the preceding week, General Grant’s remains had been quietly transferred to an 8.5-ton red granite sarcophagus and placed in the mausoleum.

The interior of the tomb features the twin sarcophagi of Grant and his wife Julia–based on the sarcophagus of Napoleon Bonaparte at Les Invalides in Paris. The remains of Grant’s wife Julia, who died five years later, were placed in a sarcophagus next to the general. Today, the busts of some of Grant’s acclaimed generals can be seen placed in the circular wall surrounding the sarcophagi. This was project was completed in 1938 under the Federal Art Project, thus making the circular room even more similar to that of Napoleon‘s, which features busts of his generals as well.

Throughout the years, despite one restoration project in 1938, the monument was subject to severe negligence; graffiti marred the tomb while trash was heaped up around the monument; the recesses were used by drug dealers and the homeless. The remiss and abuse to the monument continued until 1991 when Frank Scaturro, a Columbia University student launched an initiative to restore the tomb, ultimately raising the matter to Congress.

At the time when Frank Scaturro was a student at Columbia University the tomb was in a terrible state, with only three maintenance workers and three rangers on daytime duty. After many unsuccessful attempts to get the National Park Service (NPS), who was in charge of the monument, to take actions, Scaturro went public with a 325-page document that disclosed the negligence of the NPS and the condition of the site. Scaturro stated, “I only did what I did because I had no other resort.” The media attention drawn from the document, which was ultimately sent to the president and Congress, led to a $1.8 million grant to restore the tomb. The legislation sent by the House required that the restoration be completed by April 27, 1997, in time for the tomb’s 100th anniversary and General Grant’s 175th birthday.

Today Grant’s Tomb is open between 9:00 a.m and 5:00 pm from Wednesday to Sunday.

Next, be sure to check out our Top 15 Secrets of Columbia University in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter