Koryo Books: Where K-Pop Fans and Book Lovers Converge in NYC

Established over 40 years ago, this Koreatown store has evolved from a community bookshop into a global cultural destination!

Photo by Amy Cools

On the occasion of the month of his birth in 1818 (the exact day is not known), let’s follow Frederick Douglass in New York City. As a young man, Douglass escaped from slavery in Maryland, and his destination was New York City, to the home of David Ruggles. A free man of mixed race descent, Ruggles helped escaped slaves find new, safe homes in the free North. And this same man married Frederick Douglass to his love Anna Murray, a free black woman who sold her mattress and saved her hard-earned money to fund Douglass’ escape and who became his life-long partner and mother of his children.

S. William Street today. #13 is the Dutch-inspired building on the far left, constructed after the time of Douglass, but the foundations from an 1830 building are still present and viewable.

One: Douglass may have visited the railroad depot which was on this street. In early drafts of his autobiography The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass accidentally referred to the Philadelphia depot on Willow Street, from which he took the train towards Manhattan, as the ‘William Street depot’. This slip of the tongue (pen?) may indicate that he did go to William Street that day, or at least he was familiar enough with the William Street depot for it to come more readily to mind. When Douglass took the ferry from New Jersey to Manhattan, he would have disembarked not too far from here, and as he tells it, he slept on the docks before making his way north on Broadway.

Two: In any case, some of the structures on William Street date existed there at the time of Douglass’s flight to freedom in 1838, including the original brickwork found at 13 S. William Street. This part of town suffered a serious fire in 1845, but some of the rebuilt structures in that town retain the original foundations, brickwork, and stonework.

Photo by Amy Cools

There is a historical plaque on 13 South William Street, the one with the year 1903 prominently displayed near the pointy top. That is the year it was rebuilt after a fire in a more fashionable Dutch Revival style; the original building was under construction when Douglass was here in New York City in 1838, and the foundations remain. The buildings’ other entrance is on Stone Street, to the east and parallel to S. William St as it curves around and up in a northeasterly direction. New York City atlases show that the streets here retain their shape and direction from Douglass’ days here. So even if Douglass didn’t come to the William Street depot when he arrived, he was near this part of town, this is one of the few places where anything still stands from that time

Also see this spot on our upcoming tours of the Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

Photo by Amy Cools

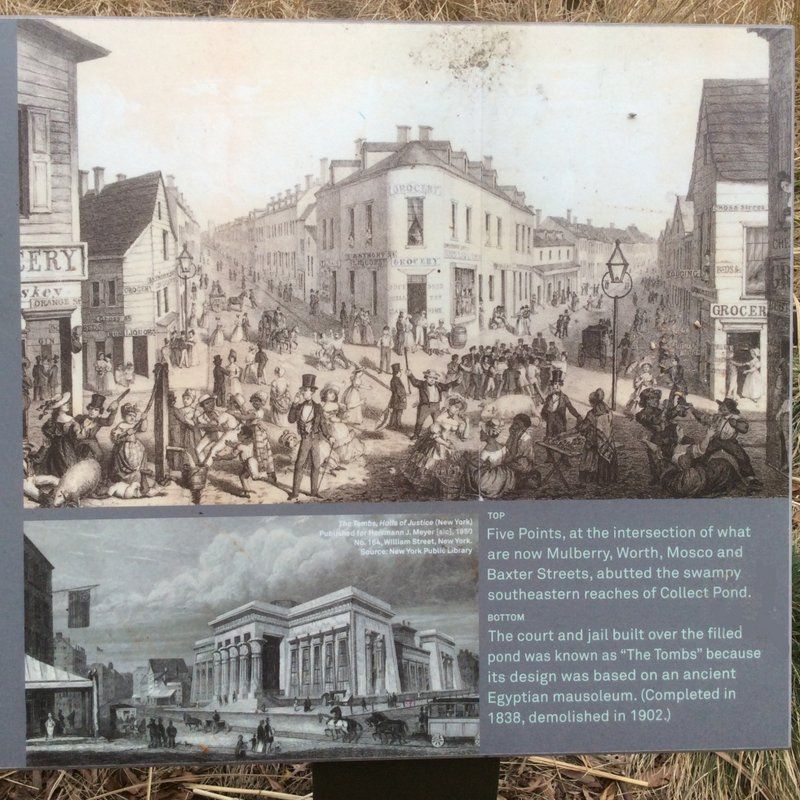

The Tombs stood at the site where Collect Pond now stretches between Lafayette and Centre Streets, at cross streets White and Leonard. It was an Egyptian revival building (hence the name, as in ancient Egyptian tombs) repurposed as a prison because it was ill-suited for its original purpose. In his autobiography The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass recalled meeting a sailor named Stuart who saw him across the street from where his house stood on the west side of that street. Stuart took an interest in him and befriended him right away. We’re sure it had much to do with Douglass’ appearance, since he dressed as a sailor himself for his escape: sailors were held in especially high regard in this part of the world at this time, so he felt he was less likely to be challenged, and since many black people were employed as sailors, he felt he’d more likely pass without notice.

Photo by Amy Cools

Douglass’s new friend Stuart gave him shelter for the night. Since, as Douglass wrote, Stuart lived across from The Tombs on Centre Street, his house would have stood somewhere on the grounds now occupied by the enormous New York City Criminal Court Building.

Looking up at the words engraved across the center front, something struck me. I imagine what Douglass would have felt that day if he knew that Thomas Jefferson’s phrase ‘Equal and Exact Justice to All Men of Whatever State or Persuasion’ would be etched in stone one day above the place his head lay. After all, it describes very well the central driving principle of his life.

The next morning, Stuart the hospitable sailor accompanied him to David Ruggles’ house located in what is the neighborhood of Tribeca today. Ruggles was a free black man and an officer on the Underground Railroad, and he had sent for Douglass, inviting him to stay at his place for the next few days at the corner of Church and Lispenard Streets. While Douglass hid out here, he sent for his sweetheart Anna, who had done so much already to help him escape by providing him with his sailor disguise and selling one of her feather beds for travel funds. In fact, she had likely met him on one of the docks at Fell’s Point. When she heard of his successful escape, she came from Baltimore immediately to join him. They were married here at Ruggles’ house on Sept 15, 1838.

Photo by Amy Cools

The Cooper Union building has had about as many great speaker’s voices echoing down its halls as you could wish for, including Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain, both friends of Douglass. In November of 1861, Douglass delivered a speech here forcefully calling for the immediate emancipation of all slaves and for the enlistment of black soldiers into the Union Army, which would not be allowed until a little over a year later.

Douglass felt it was all-important that black people should be at the forefront of the Civil War, which everyone knew, and still do if they’re being honest, was more about slavery than anything else. Not only would this prove to their fellow Americans that black people were as brave and able as anyone else, as too many Americans both north and south had trouble believing at that time, it would give soldiers the opportunity to improve their own fortunes by establishing them as heroes, and by instilling in them that sense of confidence and self-worth born of taking their own destinies finally and firmly into their own hands.

Douglass returned to Cooper Union to speak more than once. On another occasion on May 30th 1865, Douglass memorialized the recently martyred Lincoln and denounced the New York Common Council for not allowing black people to participate in Lincoln’s funeral procession in New York City.

Photo by Amy Cools

On April 9th 1870, ten days after the ratification of the 15th Amendment, the American Anti-Slavery Society met at Apollo Hall for the last time. In his speech, Douglass said that the best and really the only way to thank God for the victory over slavery and the newly won right to vote (the 15th Amendment was ratified just that February) was by thanking the men and women who made it happen, because only through them was the will of God apparent.

He was sometimes criticized in editorials and in the pulpit, especially by other black ministers, for not prioritizing God in his writing, in his speeches, and his public statements of gratitude. Douglass would have none of it, saying that as long as people did nothing about the injustice and evil done in the world, it was never done at all; the insistence on prioritizing the role of God in the good that’s accomplished can lull people into thinking that, as we sometimes put it today, it’s okay to just hang back and ‘let go, and let God’. He believed, instead, that God’s will is done on earth when people take it upon themselves to do good. Douglass didn’t think his work or that of his fellow activists here was done with the passage of the 15th amendment. He called for a new campaign for women’s suffrage, and he said that the mission didn’t end, only changed, to improve the lot of all suffering people, including Indians, women, and all oppressed minorities.

In another landmark moment at Apollo Hall, delegates nominated Douglass as a candidate for Vice President on May 11, 1872, on the ticket of the women’s and labor rights activist and Presidential candidate Victoria Claflin Woodhull of the newly formed Equal Rights Party.

In late 1892, Douglass came again to New York City to visit the marvelous Ida B.Wells, whose investigative journalism into lynching of black people inspired and informed his later speeches and activism. He almost certainly came to visit her at this site. Wells had moved to New York City in late 1892 for a short time before settling in Chicago, and in that time became a writer for and part owner of The New York Age, a very influential black newspaper which thrived for decades; that paper and Wells’ powerful pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases were printed here.

Lynching was not, for a long time, a central issue for Douglass nor for many fellow abolitionists. However, when Wells’ friends were lynched on trumped-up charges following a business dispute, Wells was galvanized. She saw, firsthand, how lynching was a terroristic weapon to keep black people subjugated through fear. Her pioneering, tireless, and hard-hitting journalism on the subject convinced Douglass to join her cause.

Next, check out 10 Stops on the Underground Railroad in NYC and 15 ways to celebrate Black History Month in NYC. This article is adapted from the piece ‘Frederick Douglass New York City Sites’, published at ordinaryphilosophy.com as part of Amy Cools’ history of ideas travel series on Frederick Douglass.

Subscribe to our newsletter