Black Friday Sale 🎊

Explore overlooked city sights on one of our expert-led NYC walking tours!

It is not only New York’s famous buildings that make it such an exciting city to explore, but at least as much its forgotten landmarks waiting to be discovered. Such a building is 280 Broadway, which sits just north of City Hall Park on a full block front between Chambers and Reade streets. Ask New Yorkers about the building and most would probably give a blank stare. Calling it by one of its historic names, the Stewart or Sun Building, probably won’t help many recognize it either.

Yet this “marble palace” was once one of the most celebrated buildings in New York and is viewed by architectural historians as one of the most influential of the 19th century. It is credited as the first department store in the country, built by retailer Alexander Turney Stewart after his dry goods business, A.T. Stewart & Co., outgrew a smaller space on Broadway.

Stewart developed the building at 280 Broadway in three phases, with the initial section at Broadway and Reade Street opening on September 21st, 1846. He expanded it south to Chambers Street in 1850 and east to the center of the block in 1853. He became one of the richest men of his time and in 1862 he opened a bigger store at Broadway and 10th Street, with 280 Broadway becoming home to his substantial wholesale and office operations.

Following Stewart’s death in 1876, it was converted to offices and two stories were added in 1884. It housed a mix of city agencies and private companies for the next few decades. The New York Sun newspaper moved there in 1919 and renamed it the Sun Building in 1928. That title still appears on the building, despite the fact the Sun left in 1950 when it was absorbed by the World-Telegram and the City of New York has owned it since 1966.

Regardless of what one calls it, 280 Broadway is one of the oldest non-residential buildings in New York City and full of interesting and unexpected history. Here are ten of its most intriguing secrets.

Photo courtesy National Park Service

Photo courtesy National Park Service

280 Broadway sits on part of the African Burial Ground, which was used by New York City’s population of enslaved and free blacks for about 100 years, from the late 17th to the late 18th centuries. The 6.6-acre cemetery extended from Broadway to Centre Street and was located on the outskirts of the city. However, the black community, which had few other options for burial of its dead, did not own the plot so as the City grew in the late 1700s new buildings and streets were built there, removing all visible traces while the burials remained beneath.

During construction of a new federal building directly north of 280 Broadway in the 1990s, extensive remains from the graveyard were uncovered, leading to the creation of the African Burial Ground National Monument. Given that part of 280 Broadway lies directly on the cemetery, it is likely that there are burials underneath it.

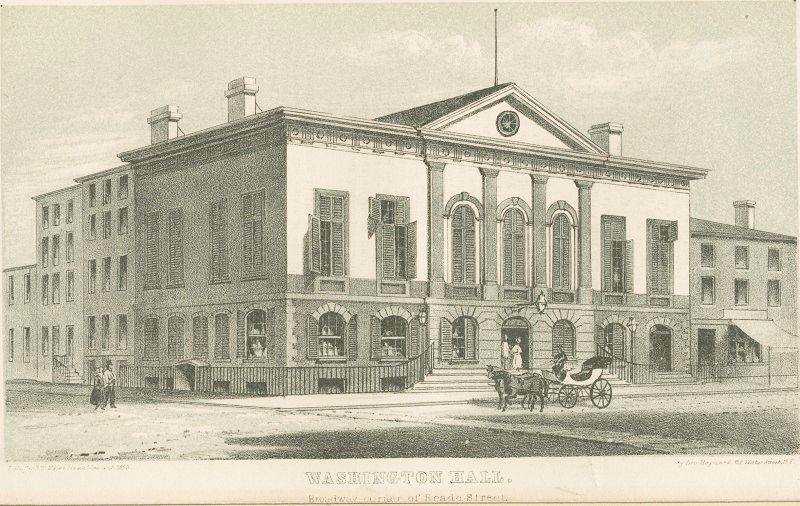

Washington Hall (1828). Via New York Public Library Digital Collections

Decades before A.T. Stewart came to this site, the Washington Benevolent Society, a political club affiliated with the Federalist Party, constructed Washington Hall at the corner of Broadway and Reade Street. Built from 1809 to 1813 by architect John McComb, Jr., who also designed City Hall, it held a meeting space for the society and a hotel. The Tammany Society, a political rival, responded with the construction of its own building, Tammany Hall, in 1811-1812.

Spurring Tammany to get its own building turned out to be Washington Hall’s primary political legacy, as the Washington Benevolent Society and the Federalists faded from the scene within a few years while Tammany Hall became a dominant force in the City for decades. The hotel meanwhile, became one of New York’s most luxurious, until a fire heavily damaged it in 1844. Rather than rebuild, the owner sold the property to Stewart who now had a site on Broadway to build his new store.

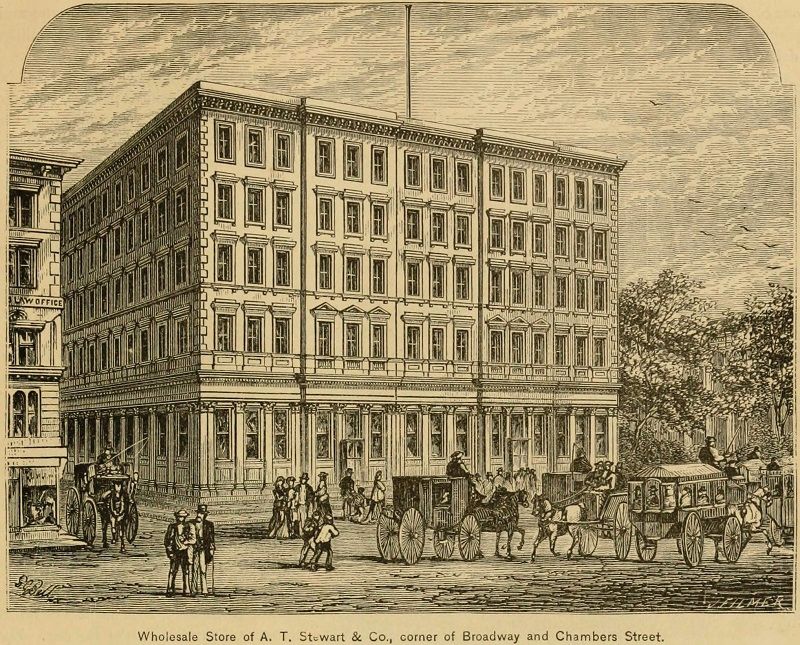

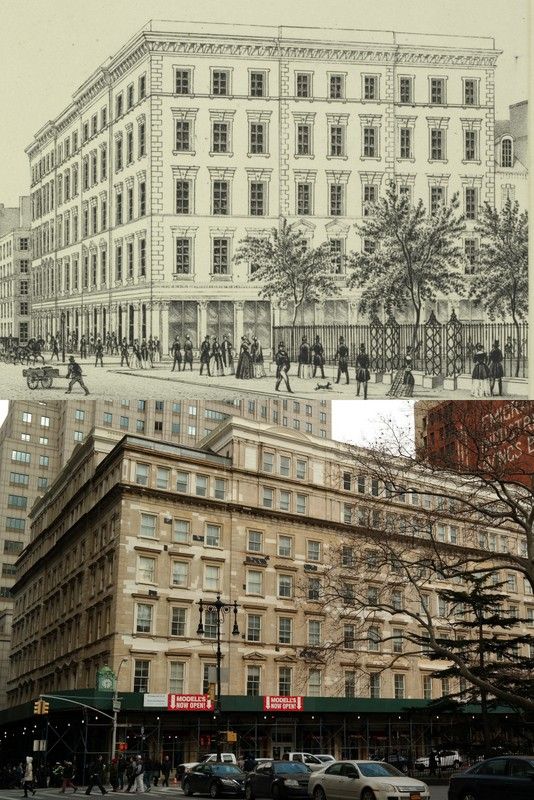

From New York Illustrated (published 1877 but appears to be early 1850s)

The “first department store in the United States;” that is 280 Broadway’s best known claim to fame, but not its only one. Designed by architects Joseph Trench and John B. Snook to resemble an Italian palazzo, it is considered the country’s first Italianate style commercial building and an architectural catalyst for a wave of palatial commercial buildings along Broadway.

With its white marble walls, plate glass windows, and ornamented interior, its impact was immediate and enduring. Even before it opened newspapers called it a marble palace, which became its unofficial name. More accolades followed. An 1854 magazine description was typical in its adoring tone: “it rises out of the sea of green foliage in the park, a white marble cliff, sharply drawn against the sky.”

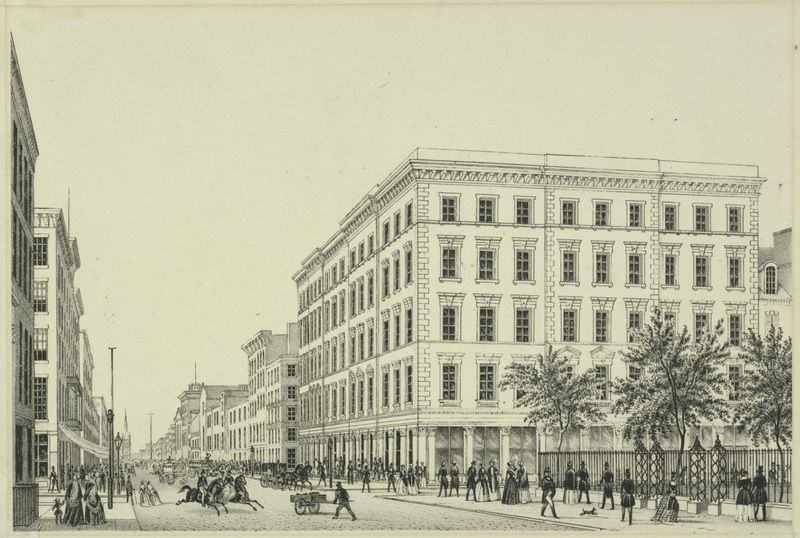

A.T. Stewart & Co. (ca. early 1850s). Enos Collection. Via New York Public Library Digital Collections

As the founder of America’s first department store and first commercial palace, A.T. Stewart became a leading merchant prince of his era. Rather than a rags to riches story, his was more lace to riches.

An immigrant from Belfast who was raised by his grandfather after being orphaned as a child, he used his inheritance to import lace and other Irish products and opened a dry goods store on Broadway in 1823. He pioneered a “one-price” policy for all products and his business thrived, enabling him to build the marble palace.

Stewart also branched out into other endeavors. These included founding Garden City, Long Island, becoming a major art collector, and almost serving as treasury secretary in 1869. (He had to decline the appointment due to concerns about conflicts of interest with his business dealings.)

After his death, his company faltered and eventually became part of the Wanamaker’s chain. His name gradually receded from the public memory to the point that he is mostly forgotten today.

Woolworth Business Card. Courtesy of Woolworths Museum

In 1888, as Frank W. Woolworth was building his retail empire of “5 and 10” stores, he established his headquarters in the Stewart Building. It was a fitting place to conduct business; he admired A.T. Stewart and wanted to follow his path of innovation and success. Just as Stewart revolutionized shopping with his fixed pricing policies, Woolworth grew on the simple premise of selling all products for a nickel or dime.

Woolworth maintained his executive offices in the Stewart Building for a quarter-century until capping his rise to the top of the retail world in 1913 with the completion of the Woolworth Building three blocks to the south. He made a comeback of sorts five years later, opening a store in 280 Broadway in 1918.

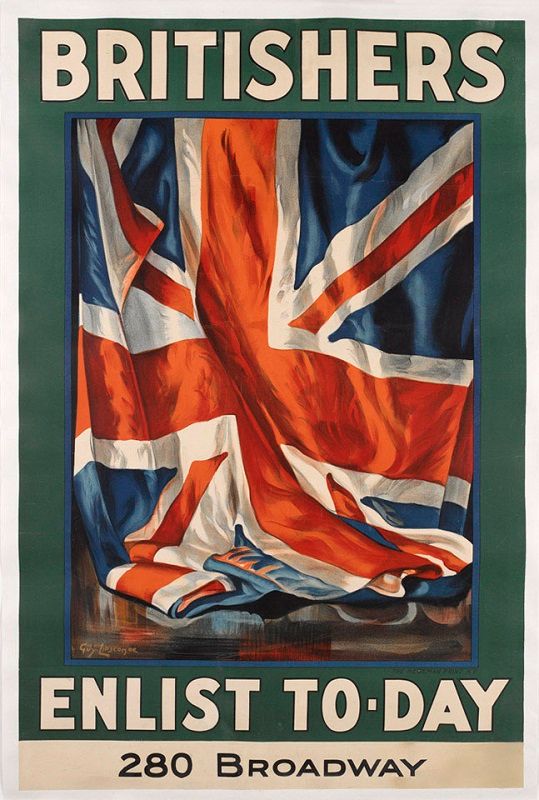

Poster by Guy Lipscombe. From Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

During the First World War, the British government had a military recruiting station in 280 Broadway for expat Brits and Canadians in the United States. To assist with these efforts, the British created a recruiting poster directing volunteers to the building.

Another wartime poster noted that the building was also home to the Emergency Fund Committee of the Navy Relief Society, which aided families of American sailors killed in the war. Not to be outdone by the British or the Navy, the US Army also had a recruiting station in 280 Broadway, though we haven’t found any Army posters referencing the building.

The survival of 280 Broadway was more a matter of happenstance than intention. Over the course of the 20th century, it was saved by cheaper real estate, wars, death, municipal inertia, fiscal crisis, and, finally, by landmark protection.

During the early 1900s, 280 Broadway was considered as a site for either a new municipal building or a new courthouse, but less expensive sites were selected for those projects. When New York Sun owner Frank A. Munsey bought the building in 1917, he planned to replace it with a skyscraper but soon dropped those plans due to high building costs related to World War I. Reports that Munsey was reviving plans for a new building surfaced a few years later but before he could act on them he died in 1925. In 1951 a new building owner announced plans for a 40-story tower on the site. But, 280 Broadway was saved again by war. With high steel prices due to the Korean War, the old building was upgraded instead and then sold in 1952.

In 1960s, the City once again looked to redevelop 280 Broadway. As part of a comprehensive Civic Center proposal by architect Edward Durell Stone, the City unveiled plans for a 54-story municipal building to replace 280 Broadway and neighboring buildings. Sporting goods executive Henry Modell, who had a store and his executive offices in 280 Broadway (following in the footsteps of Stewart and Woolworth) was a leading opponent of the new building proposal.

The Civic Center plan was approved and the City acquired the property, but the project stalled. As an interim measure, 280 Broadway housed municipal offices. A City official stated in April, 1975 that the plan for a new building was “not legally dead but not awakened from its slumbers” and in the meantime the City had no plans to either renovate or demolish the structure. But, with the City teetering on the precipice of bankruptcy later that year, the ambitious Civic Center plan was dead for good.

The preservation of 280 Broadway was only assured when this uniquely historic building was designated a New York City Landmark in 1986.

In late 1925 the Metropolitan Museum of Art became the landlord of 280 Broadway. When Frank A. Munsey passed away that year, his will unexpectedly turned over most of his holdings, valued at $17 million (equivalent to $233 million today), to the Met, at the time the largest gift the institution had ever received.

While the Met quickly sold off the Sun and other Munsey publications, it held on to the building until 1928, when it sold the property to the Sun’s new owner, William Dewart. With the purchase, Dewart renamed 280 Broadway the Sun Building and added that name to the facade, an indication that he intended to keep the building for awhile.

Besides the “Sun Building” letters on the facade, two other relics’s of 280 Broadway’s New York Sun era are the clock and thermometer mounted on the building, the former on the southwest corner and the latter on the northwest corner. The four-face clock and the two-face thermometer feature the newspaper’s logo and motto: “ The Sun – It Shines for All.” The Sun Clock was installed in 1930, the Sun Thermometer in 1936, and both underwent repairs in 1943.

By the mid 1960s, both had stopped operating and an advocacy group, the Friends of the Old Sun Clock, raised money for the clock’s repair (Henry Modell was one of the benefactors). It started ticking again in 1967. (At that time, a sign on the thermometer read “Please Somebody Fix Me Too.” From the look of the photo above, there was still a problem in 2007. (Now the thermometer is covered by scaffolding.)

Yesterday (ca. early 1850s) and Today

Today, 280 Broadway is home to the City’s Department of Buildings, which moved there in 2002 after a major renovation. There are also retailers in the base of the building, including a Modell’s store in the space once occupied by Woolworths, and a dance studio.

To be sure, part of 280 Broadway’s relative obscurity may be attributable to its current condition. Its aging facade shows many signs of wear and tear and patchwork repairs. More ominously the building has been rimmed by sidewalk sheds for years. A parking garage in the cellar was closed in 2016 following a ceiling slab collapse.

Some help may be on the way soon. In December 2016 the City awarded a $17.8-million contract for exterior rehab. According to a Landmarks Preservation Commission report (PDF), this will include facade restoration to match historic color and texture, measures to protect the building from water infiltration, and repairs to the clock and thermometer. Perhaps the marble palace will once again be a star of Lower Broadway.

Next, read about lost mansions including A.T. Stewart’s Libbey Castle, Woolworth’s Gilded Age office, and ghosts of newspapers past. Contact the author @Jeff_Reuben.

Subscribe to our newsletter