How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

In 1987, local residents and urban preservationists joined forces to save the Eldridge Street Synagogue—one of the first erected in the United States by Eastern European Jews. The 20-year, $18.5 million endeavor, called the Eldridge Street Project, culminated in December 2007, transforming the iconic Lower East Side institution into the stunning architectural marvel it is today.

It presently sits on a crowded street between Canal and Division, framed on all sides by multi-story brick buildings that house an eclectic collection of stores. With its Moorish Revival style arches and stained-glass windows, it’s easy to forget that the structure was once in a dire state of disrepair.

In celebration of the synagogue’s 120+ history, we’re hosting an after hours tour on Thursday, February 23rd that will delve deeper into its backstory. In the meantime, let’s take a closer look at some of its most notable architectural and design highlights, from its domed ceilings to its dented wooden floors.

Secrets of the Eldridge Street Synagogue After Hours Tour

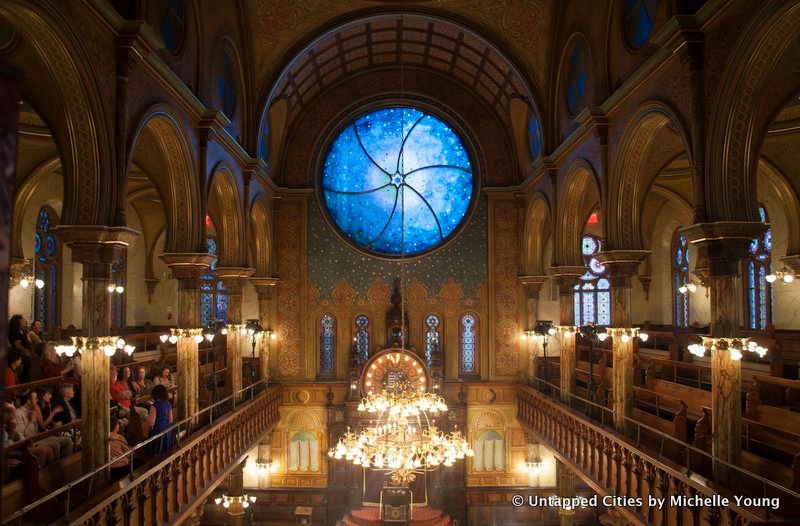

The Eldridge Street Synagogue is home to 67 stained glass panels that are arranged into sets. Walk inside and you can spot rectangular windows on the sides of the sanctuary and keyhole windows across the facade. In addition, roundels are found in the vestibule and arched windows decorate the area around the balcony and in the stairwells.

The windows incorporate similar elements into their designs: Stars of David, intersecting circles and thick cast-glass “jewels.”Although they date back to the late 19th century, they were restored between 1986 and 2007. According to the Museum at Eldridge Street, roughly eighty percent of the original colored shapes have been reused. The pattern for all windows in each set is identical, but the colors in each panel are purposely alternated by the artists.

Stained glass is a common feature seen in many religious institutions because of its aesthetic beauty. However, it also served an utilitarian purpose, as the windows were used to depict religious stories when literacy rates were low. The windows also help to foster a “grand and holy atmosphere,” as light is able to filter in, without allowing visitors to get distracted by what’s taking place on the outside; this is especially necessary for the Eldridge Street Synagogue, which sits on a bustling Lower East Side street.

The Eldridge Street Synagogue was built in 1886-87 as a house of worship for the Kahal Adas Yeshurun congregation. Designed by Roman Catholic tenement builders, Peter and Francis Herter, the building took one year and $91,907.61 to complete (or $2,234,140 in 2016 dollars when adjusted for inflation). Complimenting its intricate interior is its equally elaborate Moorish Revival exterior, which proudly displays the building’s ties to Jewish identity. Again, you’ll notice the Star of David featured on throughout the building: on its wooden doors, roof-line finials and terra-cotta bands.

Designers, who were commissioned to develop Jewish synagogues, were given quite a bit of aesthetic flexibility. That’s because the only Jewish law regarding synagogue architecture was that the sanctuary should be oriented in the direction of Jerusalem. Other than the Moorish style, the Eldridge Street Synagogue also features a Gothic rose window and Romanesque masonry. In addition, the Museum at Eldridge Street suspects that the architects might have designed the building with consideration to numerical symbolism. For instance, the five keyhole windows below the Rose Window could symbolize the five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), and the 1o tablets on the rooftop have been said to relate back to the 10 Commandments.

When the Eldridge Street Synagogue first opened to the public, it was dimly lit with hundreds of gas jets. At the time, synagogue members used lamps fueled by coal, lard, kerosene and other substances that had a tendency to give off odors. Electricity was introduced into the facility decades later in 1907, and a crown of light bulbs was consequently installed around the wooden tablets that depict the Ten Commandments in Hebrew. Even after the restoration, the bulbs and 19th-century gas fixtures have all been maintained. If you study the picture above, you may also notice that the bulbs are left bare—that’s because the congregation was excited by the new technology and felt that they didn’t need any adornment, states the Museum.

Aside from the Eastern Rose Window, which we profiled in an earlier piece, the Eldridge Street Synagogue is home to a brass Victorian Chandelier with 75 bulbs that hangs from the central dome. Back when the building was still illuminated by gas, the chandelier’s glass, flower-shaped shades were used to shield each flame. However, with the introduction of electricity, the wires and shades had to be inverted in order for more light to shine down onto the sanctuary.

Although the central chandelier is the most notable, it is not the only one you can find inside the synagogue. There’s the vestibule chandelier—the only one that uses pink glass—and the Women’s Chandelier, which is made of crystal. It looks quite different from the central and vestibule fixtures because it was not included in the original design of the synagogue. Strangely, there’s no record of its purchase or installation, although the Museum believes it most likely came from a congregant’s home through a donation.

If you have a chance to sit in the pews of the synagogue, take some time to check out the pine floorboards beneath you. By sliding your feet along the surface, you’ll feel a slight dip in the wood, which stands as a mark left behind by generations of visitors.

The snuff box located on the building’s lower level visitor center is described as one of the most “unusual features of the architecture at Eldridge Street.” During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, smokeless tobacco (dry and moist snuff) was often used as a substitute for cigarettes, especially when users could not smoke indoors or find the time for a cigarette break. Because it was such a common habit, the congregation at the Eldridge Street Synagogue provide communal chewing tobacco, contained in a wooden snuff box; it also used a portion of their funds to purchase new spittoons every year and had strict regulations regarding spitting on the floors.

To this day, the Eldridge Street Synagogue is committed to welcoming people of all faith and cultures through its doors. A Museum press release outlines this commitment:

“Our gateway Lower East Side neighborhood – once home to the largest Jewish community in the world – is today a part of a vibrant Chinatown. At the Museum, we welcome thousands of students who are themselves immigrants or children of immigrants from Asia, Latin America and other parts of the world. When learning about the Eldridge Street Synagogue, these young children understand that their experience is just the most recent chapter of a centuries-old story. We welcome as well tens of thousands of visitors of every faith and culture, and from every corner of the world, many of whom have never before entered a synagogue.”

Today, an engraving on the building’s facade is a lasting testament to this mission. Because the founders of the synagogue wanted it to be open to all, they did not use a town as part of its name; rather, the engraving simply states the name of the congregation.

Join us for our After Hours tour at the Eldridge Street Synagogue next Thursday, February 23rd led by Rachel Serkin, the Senior Educator at the Museum at Eldridge Street, with a special presentation by the Museum’s curator Nancy, about the new Postcards Exhibit.

Secrets of the Eldridge Street Synagogue After Hours Tour

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Eldridge Street Synagogue and The Secrets of Eldridge Street Synagogue’s Eastern Rose Window.

Subscribe to our newsletter