The highly anticipated launch of Citywide Ferry Service this summer will redefine how New Yorkers explore and experience the East River waterfront. Apart from the resurgence of ferry transit in the last decade, generations of New Yorkers have grown up without a connection to ferries or a sense of water as a vital link between the boroughs. The return of ferries to our lives and communities is a historic opportunity to dig into the secrets of our waterfront neighborhoods and explore New York’s glorious but largely hidden ferry past.

Here are 10 fun ferry-related historical facts about the New York City waterfront:

1. The Hamilton Avenue Ferry: An old link and district in Red Hook lost to post-war development

In the 1850s, Brooklyn’s Union Ferry Company operated seven routes to lower Manhattan. The southernmost of these was the Hamilton Avenue Ferry, which began in 1846. The ferry landing was situated at the tip of Hamilton Avenue, near the burgeoning operations of the Atlantic Basin, which was built by the Atlantic Dock Company in 1844. The Hamilton Avenue Ferry

provided transportation for Atlantic Dock Co. employeesand later, other Red Hook workers and residents.

A entertainment district called Ferry Place sprang up around the landing, and lasted through the 1930s. In the 1940 and 50s, Hamilton Avenue was transformed by construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. Ferry Place was later incorporated into the Red Hook Container Terminal, developed in the 1980s by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Thanks to community input and advocacy, Red Hook’s Citywide Ferry Service stop will be sited at Clinton Wharf in the Atlantic Basin, near the Brooklyn Cruise Terminal.

2. The Fulton Ferry Terminal: the gateway to Brooklyn since before the American Revolution

Fulton Ferry Terminal, 1863. New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Fulton Ferry Terminal, 1863. New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Fulton Ferry landing’s history of ferry service goes back over 300 years. The earliest Brooklyn ferry house was built there circa 1700, with a distinctly Dutch stepped roof. In 1730, the Montgomery Charter claimed the Brooklyn shoreline as part of Manhattan, and the property of King George II. Brooklyn residents protested by burning down the ferry house in 1748.

When Robert Fulton pioneered steam-powered ferry service to Manhattan in 1814, Old Ferry Road was rechristened in his honor (Today, it’s called Old Fulton Street). As the ferry business entered its golden age, the Union Ferry Company solidified its monopoly on service between Brooklyn and Manhattan. In 1865, they built a grand Fulton Ferry terminal, using cast-iron construction. The Union Ferry building was torn down in 1926, but survives in late 19th-century photographs.

3. The Life of the Fulton Ferry: the ferryboat that forged a city before bridges and tunnels

Brooklyn Heights

The Fulton Ferry was essential to the development of Brooklyn Heights, often called America’s first suburb. Shortly after inaugurating the new service, Robert Fulton secured a long-term lease on the ferry, which helped Brooklyn obtain its village charter in 1816. In the next four decades, the area became a commercial and industrial epicenter to rival Wall Street. At one point, the annual ridership of Brooklyn ferries exceeded the total population of the United States.

By the 1860s, the East River was overcrowded with boats, which led to serious collisions, and catalyzed the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. When the Bridge opened in 1883, Brooklyn ferries lost a substantial portion of their ridership, and many small companies went out of business. As the most successful interborough ferry service, the Fulton Ferry continued into the 20th century, despite competition from bridges and tunnels. It was formally terminated in 1924.

4. Connections between Williamsburg and the Lower East Side – a grand journey across the East River

Grand Ferry Park

Unlike Citywide Ferry Service, 19th century ferries did not connect neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens. Rather, these routes took commuters directly to points in lower Manhattan. Whereas the Union Ferry Company commandeered the South Brooklyn crossings, smaller operators in Williamsburg sought connections to the Lower East Side.

In the 1840s, the neighborhood had three Manhattan crossings: One was a short route from Grand Street to Houston St; another, called the Grand Street Ferry linked Grand Street to Grand Street in Chinatown (Grand Ferry Park, which opened next to the Williamsburg Bridge in 1988, is named after this ferry); a third traveled from Division Avenue all the way down to Peck Slip, a distance of over 1.6 miles, by far the longest route on the East River. The Citywide Ferry Service Rockaway route spans 16 miles to lower Manhattan, over 10 times Williamsburg’s 19th-century record.

5. Greenpoint: Java Street Belgian Block – Where 19th century cobblestones meet a 21st century shoreline

All along the Brooklyn waterfront, one finds remnants of the borough’s residential, commercial and industrial past. One of the most distinctive details, belgian blocks can be found in Greenpoint, DUMBO and Vinegar Hill, where historic streets have preserved some of their original paving. In the early 19th century, Belgian blocks provided solid footing for horses to traverse unpaved roads. Java Street boasts the only surviving example of Belgian block in Greenpoint, spanning one industrial block from West Street to the waterfront. The Citywide Ferry Service stop at India Street will provide a point of entry into Greenpoint’s waterfront past and an opportunity to contemplate earlier forms of transportation.

6. Pier 4 at the Brooklyn Army Terminal: a community asset and a renewed connection to the waterfront

A hundred years ago, Brooklyn’s shoreline was a forest of finger piers – long, thin, 19th century docks built for unloading steamships. In the 1960s, these structures were replaced by large, square piers, designed to accommodate trucks and containers. Since then, much of the East River waterfront has been rebuilt for new uses, including housing and recreation.

One example is Pier 4, which extends from 58th Street at the Brooklyn Army Terminal. The Sunset Park waterfront was developed as an intermodal hub for shipping and industry in the 1920s. However, for much of its post-war history, the area was singularly underserved in terms of open space and public transportation. In 1996, the 69th Street Pier in Bay Ridge closed for repairs and community organizations worked with the city to construct a public pier at 58th Street. The pier opened in 1998 and is heavily used by local residents, including fishermen. Citywide Ferry by Hornblower will provide service at both 69th Street and 58th Street, as part of its South Brooklyn route.

7. The Train Connection at Hunters Point – when trains bowed to ferries, and Hunters Point was Queens’ great commuter hub

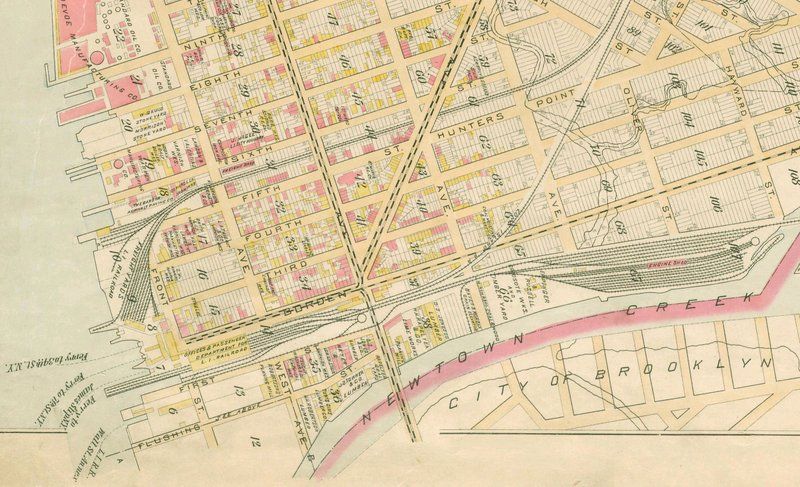

LIRR hub and ferry terminal at Borden Avenue, 1891. Map via Wikimedia Commons.

LIRR hub and ferry terminal at Borden Avenue, 1891. Map via Wikimedia Commons.

Historically, New York City ferries were divided into 3 camps: trans-Hudson services that were owned by New Jersey railroads, East River services that were run by ferry companies, and the stand-alone Staten Island ferry. There was, however, a ferry in Western Queens that was operated by the Long Island Rail Road. In the 1850s, a group of enterprising landowners decided to develop Hunters Point.

In 1859, a new ferry service was established to serve this community. The ferry ran from Borden Avenue to East 35th Street – essentially the route that carries Hunters Point ferry commuters to Midtown today. For the next 50 years, until the Pennsylvania Railroad built a tunnel between Sunnyside Yards and Penn Station, the LIRR relied on the Hunters Point ferry to transport its customers to Manhattan. The ferry was discontinued in 1925.

8. Crossing Brooklyn Ferry – New York’s history of ferries immortalized by Walt Whitman

Before bridges and elevated trains, ferries played a central role in the lives of 19th century New Yorkers. Yet, there are few paeans to the humble ferryboats or great ferry companies that traversed the East River before the advent of bridges and tunnels. The one exception is Walt Whitman’s famous poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” a contemplation on the Fulton Ferry, that looks back and forward through time. The opening lines,

“on the ferry-boats the hundreds and hundreds that cross, returning home, are more curious to me than you suppose

And you that shall cross shore to shore years hence are more to me and more in my meditations than you suppose,”

are inscribed at the Fulton Ferry landing, which opened in 1997 in what is now Brooklyn Bridge Park.

9. The Last Astoria Ferry – restoring a vital link to a pioneering neighborhood after four generations

Astoria was home to the first regular ferry service in Queens, established during the Revolutionary War. In the 19th century, Hallet’s Cove – as the neighborhood was once called – supported many maritime businesses and heavy industries. Yet, unlike other waterfront communities, Astoria has no recent history of ferry service. The last Astoria ferry ran to East 92nd Street, between 1920 to 1936, when New York City was taking over struggling ferry operators. The ferry was terminated after the completion of the Tri-Borough Bridge. Though few New Yorkers today can recall taking these ferries, Citywide Ferry Service is re-building Astoria’s connection to the East River at Hallet’s Cove. The launch of a new Astoria ferry this year will mark a dramatic end to the neighborhood’s 80-year gap in water-mass transit.

10. Fare’s Fair – The Cost of a Ferry Ride in the 19th Century

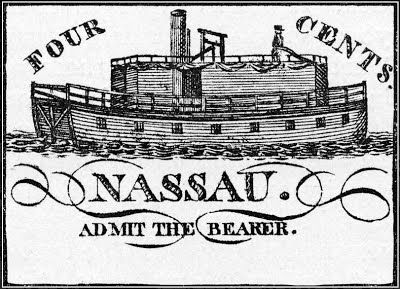

A ticket for inaugural ride of the Fulton Ferry aboard the Nassau in 1814. Credit: Brooklyn/Queens Waterfront

A ticket for inaugural ride of the Fulton Ferry aboard the Nassau in 1814. Credit: Brooklyn/Queens Waterfront

In 1814, an inaugural ride on the Fulton Ferry cost a mere four cents, but 19th century fares weren’t necessarily a bargain. In 1824, Robert Fulton lost his monopoly on ferry services in New York State, which sparked flurry of startup companies, and a half-century of fierce competition. Operators would sometimes extort customers and overload boats to maximize profits from each ferry ride.

The Union Ferry Company, established in 1839, steadily brought down fares until they were fixed at a penny. Once the company succeeded in driving small competitors out of the market, it used its monopology to double fares, angering its ridership. Today, law and order reigns on the waterfront. With Citywide Ferry Service, the cost of a ride will remain affordable, and New Yorkers will be able to travel anywhere in the system for $2.75.

Next, discover 15 must-visit spots in Astoria, Queens.