With over five hundred miles of coastline, it’s no surprise that New York City is directly shaped by the waterways that surround it. While the Hudson River has long served as a working waterfront, home to warehouses, businesses, and passing freight, it’s also an iconic city fixture in and of itself. Much like the various bridges it flows under, the river is a sight to behold — and it also happens to hold many secrets.

1. The Hudson River is Not Just a River

In-the-know New Yorkers like to point out that the Hudson River is both a river and an estuary, meaning the waters come in from multiple sources, including salt water from the sea. As Leslie Day, author of River: Living on the Hudson – A Natural History, a specialist on the Hudson River, says, “A river is a body of fresh water that flows from the mountains to the sea, which the Hudson does. An estuary is ‘an arm of the sea’ and at incoming tide flows into a river basin. So the Hudson is a ‘river that flows two ways’ – a tidal river from its estuary that brings ocean water up the river basin, and a freshwater river that flows from the mountains to the ocean. Thus, we have 2 high tides and 2 low tides every day.”

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation even goes so far as to say that the river actually “feels the ocean’s tidal pulse all the way to Troy,” 153 miles from the New York Harbor, and almost half the length of the 315-mile river. Rising tides will push the current towards Troy, and falling tide will move the water back towards the harbor. Every 24 hours, there will usually be two high tides and two low tides. When the water is frozen over during the winter, the ice will also drift both ways (south or north).

2. The Hudson River Is Also a ‘Drowned River’

The term “drowned river” may sound like an oxymoron, but it’s actually used to describe the geological state of the Hudson River estuary. After the retreat of the Wisconsin glaciation, rising sea levels have drowned the coastal plain, bringing salt water above the mouth of the river. In fact, the drowned river valley rises only about 1.5 miles along 150 miles between New York City and Troy. It’s dredged to maintain a minimum depth of 9–11 meters.

3. The Hudson River is Labeled the North River on Old Nautical Maps

The Hudson River has had several names over the years: the Mohicans called it “Mahicannittuck (place of the Mohicans),” the Dutch referred to it as “Mauritius,” in honor of Prince Maurice of Nassau, and the Iroquois called it “Cahohatatea” (the river). The southernmost portion of the Hudson River also has a nickname: the North River, which refers to the vicinity around New York City and northeastern New Jersey.

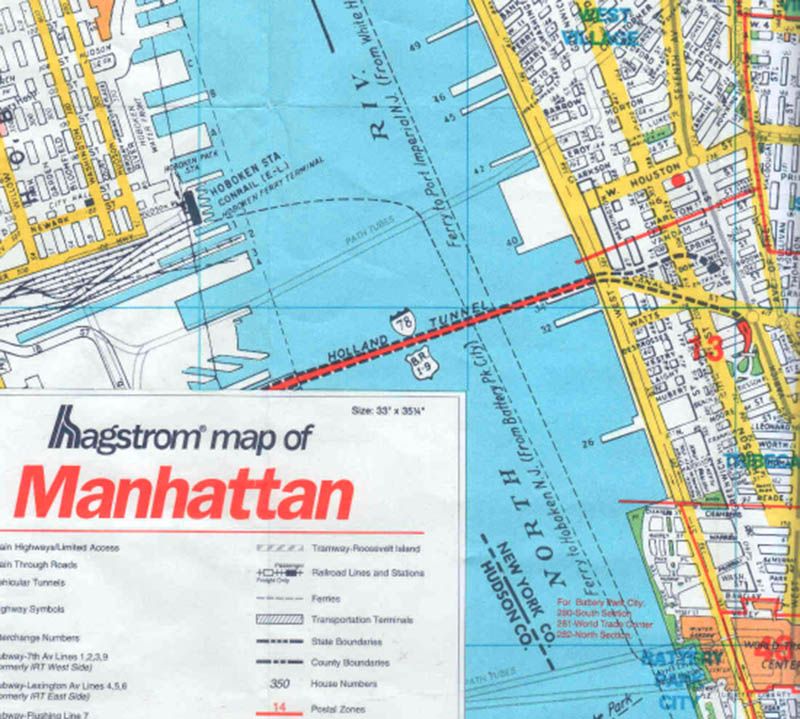

If you ask locals about the “North River” today, they’d probably cock their heads in confusion. While the term still retains currency for local mariners, it has fallen out of general use. However, on some nautical charts and maps from the 17th through 19th centuries (and even into the 20th century), what we know as the Hudson is actually labeled as the “North River.” The Hagstrom map, seen above, was published in the 1990s.

A 1909 guidebook to the Hudson Fulton Celebration attributes the origin of the nickname to the English, writing that ” … [they] more often gave it the name of the ‘North River’ … But the popular sense of justice came to call it ‘Hudson’s River,’ and that finally settled down to the ‘Hudson River.’”

As Ephemeral New York notes, however, other sources have also claimed that the Dutch were the ones who called it the North River (the Delaware being the South River).

4. There Used to Be a Floating Church on the Hudson

Manhattan is no longer a port city, and the containerization of shipping has kidnapped shore leave. There are many that mourn the old days, when carousing bands of sailors were still a threat to pure womanhood, and the only way to keep an old salt in line was with the dreadful terror of God. Meet the Seamen’s Church Institute and its floating churches.

The Seamen’s Church Institute was founded in 1834 by a group of Episcopalian sailors and operates to this day. Their first big project was the Church of Our Savior, a floating church moored off Pike Street in downtown Manhattan. The first Church of Our Savior, “an object of attention and a marked institution of our city,” according to quickly disintegrated and SCI scuttled in in 1866. A second Church of Our Savior was built, excuse me, floated, in the same spot in 1870.

Besides the Church of our Savior in the East River, the Chapel of the Holy Comforter was moored in the Hudson. In 1868, when maintenance costs became excessive, SCI disposed of this church.

5. There are Seahorses in the Hudson River

Now that we know that the Hudson River is partly an estuary, it makes sense that its waters are home to over 200 species of fishes — some more abundant than others. This list includes the Northern Pike, Striped Searobin, Naked Goby, Lined Seahorse and the occasional Humpback whale that likes to stray from the ocean. Moving upriver, the Department of Environmental Conservation notes that the salinity decreases, giving away to freshwater species like black bass and sunfish. The river’s signature fish is the Atlantic Sturgeon, which may live more than 60 years and grow up to 14 feet in length.

6. "Floating Palaces" That Could Fit 1,500 Passengers Once Traveled the Hudson River

When Robert Fulton’s first steamboat launched on August 17, 1807, it revolutionized the way New Yorkers, and the rest of the nation, navigated our waterways. When steamboats were first introduced, they were used primarily for passenger travel rather than the less lucrative transportation of goods. Steam-powered ferries carried passengers up and across the Hudson faster and for less money than any vessel could before. Until the railroad came along. With trains along the Hudson shoreline running faster and more frequently than any passenger boat, steamers became less utilitarian and more leisurely.

To serve the new market of rail riders, passenger steamers transformed into “floating palaces.” These extravagant ships whisked New Yorkers from the city up into the natural beauty of the Hudson Valley region and the Catskills, for day trips and getaways. Steamers such as the Hendrick Hudson created for the Hudson River Day Line, often boasted fanciful amenities such as grand dining rooms and saloons outfitted with hardwood furnishings. Some steamers had barbershops, and one even had a darkroom where passengers could develop their photographs! Aboard the Hudson you could find a band-stand where live music was played by an orchestra, private drawing rooms furnished in popular styles like French-Empire, electric lights, and of course an observation deck, large windows and a glass viewing dome where you could take in the stunning scenery from the Palisades to the Hudson Highlands.

The SS Columbia, from Detroit, commemorates the great legacy of historic Hudson River steamboats. After years in disrepair, the S.S. Columbia left its grave on Detroit’s industrial waterfront and made its way to Toledo for one winter, then Buffalo, New York. Check out the interior of the S.S. Columbia as of 2015.

7. A Never-Built Hudson River Bridge Would Have Dwarfed the Woolworth Building

Beneath a tree on a (landlocked) college campus in New Jersey, there’s a cornerstone of a bridge that leads to nowhere. The stone is the only trace of a planned 6,000-foot-bridge that would have spanned the Hudson River from Manhattan’s 23rd Street to New Jersey. Originally laid in June 1895 at the corner of Garden and 12th Streets in Hoboken, the stone was only later moved to its current location at the Stevens Institute of Technology. Had plans come to fruition, the massive structure would have been an iconic element of New York’s skyline.

Even by modern-day standards, the size of the bridge is impressive: 200 feet wide and 200 feet high to accommodate 12 railroads, 24 traffic lanes and 2 pedestrian walks. The massive structure would have been double the length of the George Washington Bridge, and two supporting 825-foot-high towers would have been taller than the 792-foot Woolworth Building (the world’s tallest skyscraper at the time).

Read more about the never-built structure here.

8. The Hudson River Is Also Home to a Floating Science Barge

We previously reported on the train barges that cross the Hudson River twice a day, but did you know that a “Science Barge” greenhouse also floats on the water? Developed by NY Sun Works, the prototype sustainable urban farm operates as an environmental education center. It’s been docked in the Yonkers since 2008, providing fresh produce like tomatoes, peppers and eggplant. The energy needed to power the entire system is harnessed using solar panels, wind turbines and biofuels, while rainwater and purified river is used to irrigate the crops.

Swale, a floating edible farm has also docked in the Hudson River (and East River).

9. There’s a Catalogue of Fisherman’s Tales About the Hudson River

The Hudson River Maritime Museum has an oral history collection, featuring 30 interviews with Hudson River commercial fishermen and the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation officers. Spanning between the years 1989 and 2000, the interviews and personal stories cover topics ranging from commercial fishing to water quality. Listen to them here.

10. The Hudson River Was Once Dominated by Sloops

The Clearwater Hudson River Sloop

The Clearwater Hudson River Sloop

Before the advent of Robert Fulton’s steamships, sloops — single-mast sailing boats — were the main method of transport for cargo like cement and ice in the 18th and 19th centuries. Derived from Dutch and British sloops, these vessels were specifically designed for the Hudson River. Given the right wind conditions, they could easily complete the trip from Albany to New York City at a much faster speed than rival steamships.

Although steamships would eventually become more popular, the legacy of the sloop is not forgotten. In 1966, folk music legend and environmental activist Pete Seeger set out to build a “majestic replica” of the Hudson River’s iconic sloops. Distraught over the polluted condition of the waterway, he was determined to use the vessel in a preservation effort that would help others recognize the beauty of the river.

Thus, the Clearwater was born. In 1969, the 106-foot vessel embarked on her maiden voyage from the Harvey Gamage shipyard in South Bristol, Maine. She sailed to South Street Seaport, and then made her home on the Hudson River. Today, the boat, renovated now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, serves as a moveable classroom, laboratory, stage and forum; from April through October, it sets sail from a variety of docks from Albany to New York City. The ship was renovated in Kingston.

Next, discover the Top 10 Secrets of Hudson River Park and Behind the Scenes at The Floating Freight Rail Line That Crosses the Hudson River.