♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Throughout the course of New York’s nearly 400-year history, Bowling Green has seen its fair share of historic events. As the city’s oldest public park, it’s been repurposed several times over the years, serving not only as council grounds for Native American tribes, but also as a parade field, a cattle market and an actual bowling green for lawn bowling. With such a storied history, it’s no surprise that Bowling Green is also full of secrets.

Bowling Green was designated a park in 1733, but the wrought iron fence that surrounds it also dates back to the 18th century. It was installed in 1771 to protect a giant statue of King George III that was erected in the park six years earlier by the British government. Over the years, it came to serve as a gathering place for anti-English protests as tensions rose between Britain and her colonies; while New York’s oldest fence still stands today, it bears hefty scars from this era. The fence posts, once decorated with royal crown-shaped finials, were sawed off on July 9th in an act of defiance by the Sons of Liberty.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

The NYC Department of Parks writes that Bowling Green served as an informal communal ground until the 1740s, when the Common Council — the area’s governing body — offered the land for rent at the “cost of one peppercorn per year.” The site was designated a park in 1733, and three lessees, landlords John Chambers, Peter Bayard, and Peter Jay, were responsible for developing it into “the delight of the Inhabitants of the City” with trees, walking paths and a bowling green.

Read more about how Bowling Green got its name here.

Fort Amsterdam is the large quadrangular structure towards the tip of the island. 1916 Redrawing of The Castello Plan, map of 1660 New Amsterdam via Wikimedia Commons. The wide street is now Broadway, and Wall Street is the line with guard towers on the left.

Fort Amsterdam is the large quadrangular structure towards the tip of the island. 1916 Redrawing of The Castello Plan, map of 1660 New Amsterdam via Wikimedia Commons. The wide street is now Broadway, and Wall Street is the line with guard towers on the left.

According to the NYC Environmental Protection, Manhattan’s early settlers obtained water for “domestic purposes” from privately-owned wells. In 1677, however, the first public well was dug in front of Fort Amsterdam at Bowling Green. A century later, when the population had increased to approximately 22,000 residents, a reservoir had to be constructed on the east side of Broadway between Pearl and White Streets.

To see an archeological dig of Dutch era tavern and well, join us on our next tour of the Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

The equestrian statue of King George III (mentioned in secret #1) was dedicated in Bowling Green on April 26, 1770. King George III was not the statue’s intended subject. After the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, a number of cities decided to erect a statue of William Pitt, the British Prime Minister, who instrumental in the repeal of the Stamp Act. However, the New York elders thought it unwise to have a statue of Pitt when there was no statue of King. As a result the City commissioned Joseph Wilton to design statue of both men.

In the midst of the Revolutionary War, the fate of the statue was sealed. On July 9, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read at the head of each brigade of the Continental Army posted at New York. In the furor created from the public reading, British symbols around New York City were destroyed culminating in the pillaging of the statue of King George III. The remnants of the statue were sent to Litchfield, Connecticut and made into bullets for the war effort. Today, a few pieces from the statue, possibly hidden by loyalists in Connecticut, can be found at the New-York Historical Society.

Read about other equestrian statues around New York City here.

Photo from Library of Congress

Photo from Library of Congress

According to the Bowery Boys, the first velodrome was located near Bowling Green. It featured the precursor to the bicycle, known as the “draisine,” which is defined by Museo Galileo as “the first two-wheeled vehicle purposely built for personal transportation.” Invented in 1816 by German aristocrat Karl Christian Ludwig Drais von Sauerbrohn, the draisine (or “hobby horse” as it came to be known as) had to be mounted and pushed with the foot.

Bowling Green’s famous Charging Bull statue is located at the intersection of Broadway and Morris Street, just a block north of the South Ferry building. Conceived by artist Arturo Di Modica, the iconic, 7,100-lb. sculpture was erected in celebration of the American “can-do” spirit, and over the years, it has also come to symbolize Wall Street. But the sculpture was originally installed as a piece of guerrilla art, and only later made permanent.

Many passing tourist will stop for a quick photo next to the bull, but did you know that its testicles are supposedly said to be lucky? Word on the street is that “you’ve got to rub the nose, horns and testicles of the bull for good luck.” Similarly, the penis on the Fernando Botero “Adam” sculpture at Columbus Circle has been rubbed down to a golden shine by passersby.

For more feminist fare, read on.

In contrast to the masculinity of the Wall Street Ball (or attributed to it), the statue of “Fearless Girl” was installed by State Street Global Advisors, a financial firm, and its advertising partner, McCann as a temporary piece, timed with the current political climate. [Update: she has since been moved to the New York Stock Exchange.]

The sculpture is by Kristen Visbal – and though Fearless Girl is a destination now almost as popular as the bull, the controversy over the motive of its installation have not subsided. Feminist statement or opportunist marketing stunt? The wonderful thing about it is that as a piece of art, it takes on a different meaning.

Due to popular demand (and bipartisan support), Fearless Girl will stand here until at least 2018 but there’s one very notable opponent to the idea. Arturo Di Modica, who designed the Wall Street Bull, is considering legal action against New York City for infringing “on his own artistic copyright by changing the creative dynamic to include the other bold presence.” Mayor Bill de Blasio responded in kind: “Men who don’t like women taking up space are exactly why we need the Fearless Girl.”

Engraving by George Heyward. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Our founding father lived at two residences during New York City’s short-lived term as the nation’s capital. President Washington and his wife Martha first lived on Cherry Street before moving to the Alexander Macomb House (the second presidential mansion) at 39-41 Broadway, located at the northern tip of Bowling Green. He resided there from February 23 to August 30, 1790 until the capital moved to Philadelphia.

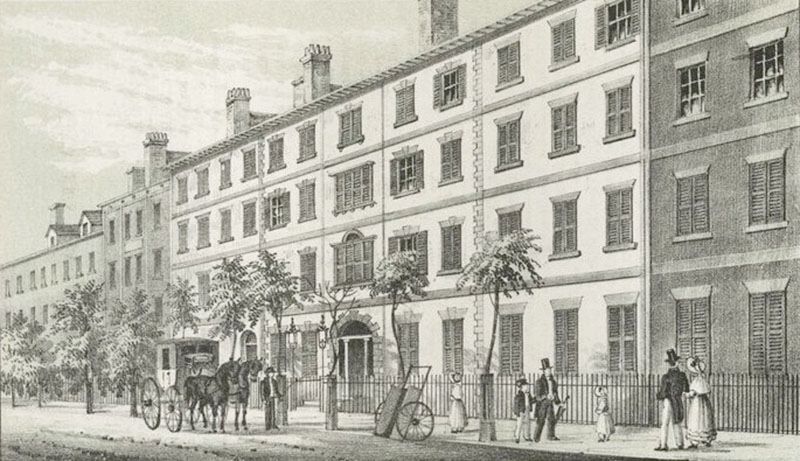

Bowling Green print from 1826. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the 1820s, some of New York’s wealthiest families had congregated around the Battery and its surrounding area. As one of the oldest settled areas, Bowling Green would eventually come to adopt the nickname “Nobs Row,” especially as revolution townhouses began to populate the surrounding neighborhood. Interestingly enough, Scientific American refers to Bowling Green as “an early example of gentrification.” In its early history, the immediate vicinity around it served as home to prominent folks like the Van Cortlandts, Livingstons, Delanceys and Bayards.

Today, Bowling Green has the Alexander Hamilton Customs House and the Wall Street Bull, but it’s importance dates all the way back to the Native America era. It is believed there was a Kapsee chief hut at the foot of the Wickquasgeck Trail, which would later become Broadway. At the foot of the trail was a large elm that would have denoted a sacred spot where council fires were held. It was also a place for trade and for meeting. From what we know of the Lenape Indian era, it is clear that the area that is now lower Broadway was a government site, a commercial site for trading, and a social site.

It would have been located at the meeting point of two rivers, now long infilled. It would have had sightlines to both Long Island and New Jersey, and have had direct access to the harbor which was important for both protection and for trade. This direct access has also long been infilled, as Manhattan’s waterfront as expanded further outward.

The Wickquasgeck trail, which was the first north south route in what is now New York City went from today’s Bowling Green all the way up to Montreal, and was a primary trading route used by many Indian tribes.

The above image is a map from the Welikia Project showing Manhattan in 1609. This online tool allows you to overlay present day Manhattan onto 1609 Manahatta and the section highlighted shows the current Alexander Hamilton Customs House at the foot of Bowling Green and Broadway coming off of it.

Next, read more about the history of Bowling Green and learn about how it got its name.

Subscribe to our newsletter