How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

Did you know that there are over 2,000 bridges in New York City? Over the years, we’ve been ardent about spotlighting them, but there are plenty of lesser known spans that remain under the radar. Today, we’re taking a look at ten of New York City’s lost or former bridges, with special assistance from Untapped Cities’ history editor, Benjamin Waldman.

The bridge depicted in mosaic in the 125th Street Station is one of the most obscure bridges in New York City history. In 1790, a charter was given to Lewis Morris to build a bridge that would cut the travel time to Morrisania (the name of Morris’ estate in the Bronx) from Manhattan. Morris was permitted to collect tolls for 60 years, after which ownership of the bridge would revert to the state. The bridge, a wooden bridge with a turntable draw span, was ultimately opened in 1797 and named after John B. Coles, Morris’ business partner. The Third Avenue Bridge, which has been rebuilt multiple times, was last reconstructed in 2004.

Also, check out other bridges depicted in subway art tiles.

Image from Library of Congress

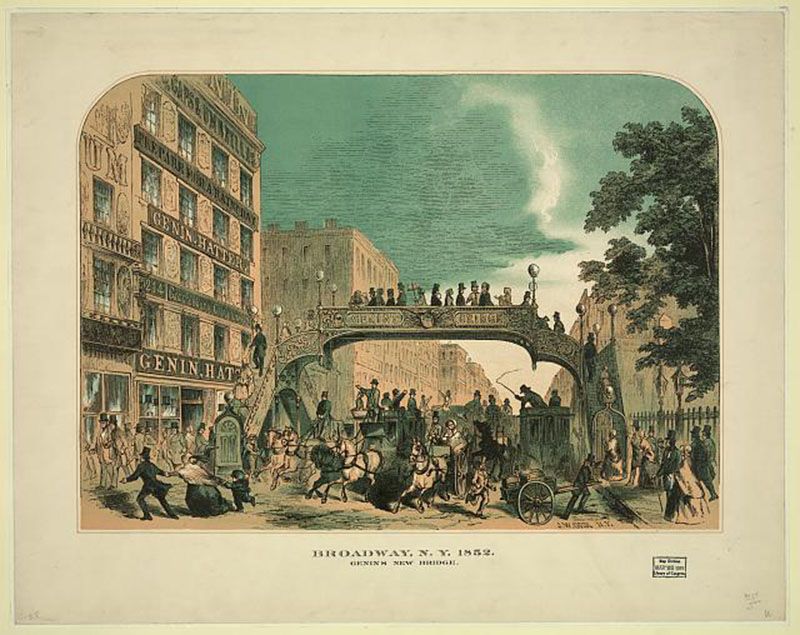

In 1852, a cast-iron footbridge was built across Broadway at Fulton Street to encourage pedestrians to cross over the crowded and busy street. Constructed in 1866, at the urging of Broadway merchants (particularly a hatter named Genin), it was generally disliked and torn down just two years later.

In 1848, High Bridge, the oldest surviving bridge in New York City was built to bring water to the burgeoning city of New York. Aside from transporting water, the bridge connected the metropolitan borough of Manhattan to the lush rural area of the Bronx, so that both city dwellers and those who lived in the country could easily travel back and forth. After being closed for over forty years, the bridge, built in the style of ancient Roman aqueducts, was opened to pedestrians in the summer of 2015.

When High Bridge was used for water delivery from upstate to New York City, 90 million gallons of water were being transported from the Croton Reservoir to New York City. To improve navigability across the Hudson River and because the masonry was considered hazardous to ships by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the five original stone arches were removed in 1928 and replaced by a single steel arch. At this time, there was a possibility that the bridge would be torn down entirely, as Manhattan now had access to other means of water including water from the Catskill region, which was funded by the Board of Water Supply in the early 1900s. Ultimately, the bridge was preserved but the water was rerouted. As Justin Davidson notes in Magnetic City, “on the walkway, the two sections [of the bridge] are demarcated by different patterns of pavers.”

In The History of the City of New York, author David T. Valentine makes mention of a former bridge on Broad Street, stating that:

The present STONE STREET, as has been before mentioned, was the line of the first road laid out from the fort to the ferry. The early occupants of that part of the road between the present Whitehall and Broad streets, were the following, their property being generally described as on “the road:” Adam Rolantsen, one hundred feet front;Arent, the smith ; Philip Geraerdy, a trader ; Oloff Stevenson Van Cortland, commissary; Harman Meyndertsen JIsaac De Foreest, brewer; Gysbert Opdyck, commissary; Pieter Cornelisen. From the character of these residents, it is to be inferred that this was one of the best streets of the town. Crossing the inlet, at the present Broad street, by a bridge, the part of the road between the latter street and the present Hanover square, was vacant on the southside, until the erection of the City Tavern, in 1642.

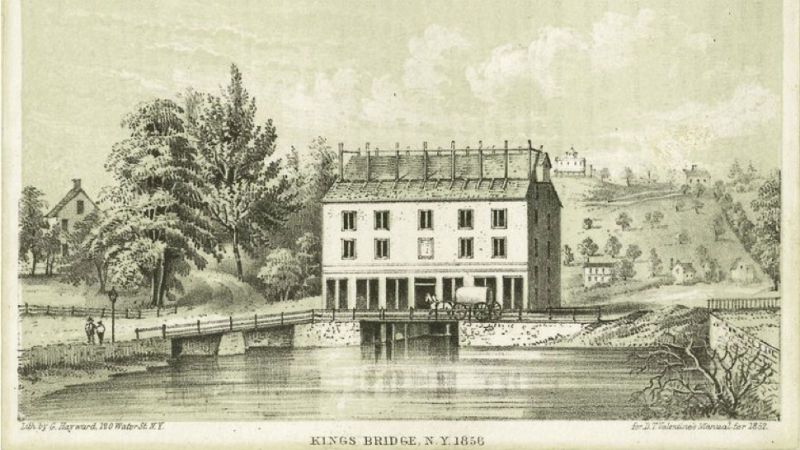

According to Untapped Cities’ History Editor, Benjamin Waldman, the original King’s Bridge (and New York City’s first) seems to have been built in 1693 and then rebuilt in 1713. The History of the City of New York hints at a bridge going over a canal that could be it:

The ” Brugh straat,” or Bridge street, still retains its name; the circumstance from which it was derived being, that it led to the bridge crossing the ditch at Broad street.

Here’s a second instance:

… we shall cross the bridge over the canal, running up Broad street, and continue our description of what was then called ” The Water,” and sometimes ” the Water-side,” designated at present as the north side of Pearl street, between Broad and Whitehall streets, the history of which is as follows : The first church built in this city was erected in 1633, on the present north line of Pearl street, about the middle of the block between Broadway and Whitehall street. This church presented its prominent front to the waiter; but the entrance was mainly from the rear, at the present Bridge street, which was then a wagon road, leading to the bridge across the ditch at Broad street.

Today, the High Bridge is New York City’s oldest bridge, but history buffs like to point out a technicality: the King’s Bridge is still rumored to exist — just underground.

In Lower Manhattan, the historic Stone Street remains reminiscent of its 17th century roots. Today, it’s home to a variety of restaurants, pubs and pizzerias, but prior to that, it was also the site of a bridge, which David T. Valentine points out again in his book:

In 1671, an ordinance was passed to improve the graftin the following manner: From the shore of the river upward to the bridge at Stone street, to be repaired, of the same width and in the same manner as before.

Read more about the history of Stone Street here.

The Marble Arch was one of the finest pieces of architecture in Central Park, located at the end of the mall, on the opposite end of Bethesda Terrace was Marble Arch. It was unique for many reasons.

First, most of the other architecture in the park is built of stone or brick. Built entirely from marble, the arch distinguished itself from its other noble neighbors and was the only bridge built of the material in the entire park. According to Edward J. Levine in the book Central Park Then & Now, the Marble Arch featured a drinking fountain, a semicircular pergola, and marble benches.

A description from 1869 deemed it “one of the pleasantest and most elegantly built of all these cool places for rest and refreshment.” Indeed, two marble staircases led down into a refuge beneath the archway. It also kept pedestrians safe from carriage traffic.

Like many things lost in New York City, we have Robert Moses and his quest for automobile domination to blame. In 1938, the Central Park drives were realigned to accommodate car traffic. The arch was demolished, smashed into pieces, and buried.

Take a tour of the Secrets of Central Park with us:

Secrets of Central Park Walking Tour

The Gapstow Bridge

When Calvert Vaux and Frederic Law Olmstead brought Central Park to life, it was home to Oak Bridge, located at the northern end of the Lake. According to Curbed NY, it was constructed of white oak and cast iron, and led into the Ramble. In the years since then, it has been replaced twice — first in the 1870s (renamed the Bank Rock Bridge) and again during the Great Depression by a “utilitarian model in tubular steel.”

Today, the original and reimagined design has been resurrected by Jan Herd Pokorny Associates. The carved white oak and cast iron has been brought back, but the bridge now rests on a sturdier base.

In addition, the Gapstow bridge is the second bridge that was erected over the Pond at 59th Street. The first one, made of wood and iron, and designed by Jacob Wrey Mould, was replaced in 1896.

When the 78-year-old Kosciuszko Bridge is demolished in 2018, it will join our list of former and lost bridges. But the current bridge is actually a replacement for the former Meeker Street bridge, as we showed in our article about the secrets of the secrets of the Kosciuszko Bridge. A replacement, cable-stayed bridge, located south of the Kosciuszko, has been under construction since 2015; it will open in 2017 with three lanes in each direction. A second, cable-stayed span will also take over the current location of the Kosciuszko once it is demolished (too much fanfare and anticipation for New Yorkers).

Next, check out 11 NYC Bridges Built Just For Pedestrians and Bikers and 15 NYC Bridges Under Construction.

Subscribe to our newsletter