NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

One of our historically popular articles blames Robert Moses for some of New York City’s infrastructure disasters (and potential ones unrealized like the Lower Manhattan expressway). But, Moses also bestowed on the city many great projects that New Yorkers continue to enjoy today. It’s just usually too easy to make fun of Moses, as many of you witnessed in last year’s musical BLDZR about Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses.

In fact, writer Phillip Lopate, author of Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan, wrote in the New York Times in 2007 that “Moses’ satanic reputation with the public can be traced, in the main, to Robert A. Caro’s magnificent biography, “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.” It seems however, despite attempts to reframe Moses in a more nuanced light in the past decade through new books and museum exhibits, it is Caro’s portrayal that continues to capture the imaginations of New Yorkers.

Today, we’re playing devil’s advocate and highlighting some of the great works of the master builder while acknowledging that there are almost always winners and losers in every development scenario, particularly here in this city.

The Riverside Park you know today is quite different from the original, opened in 1875 and designed by celebrated landscape architects Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux. About half the park, 132 acres, was added under the purview of Robert Moses, then the city’s Parks Commissioner, from 1937 to 1941. The additions were designed by Gilmore D. Clarke and Clinton Lloyd. The promenade sits above the active Amtrak tunnel, commonly known as the Freedom Tunnel, built originally by the Hudson River Railroad (later the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, under the ownership of Cornelius Vanderbilt).

Combining an auto route and concealing the active train line was considered quite a feat of engineering and design. The New York City Department of Parks & Recreation gives the architects strong acclaim, stating “They wove through this extraordinary collection of active recreation and scenic areas a vital north-south automobile artery and a railroad running in a tunnel under the entire park.” The New York Times noted in 2007 that the plan “remains a model of thoughtful urban planning.” In addition, the expansion of Riverside Park was a direct response to community pushback against additional industrial uses along the waterfront.

The park expansion also included the construction of an esplanade, the 79th Street Marina and Boat Basin, ball fields, and a rotunda.

To understand the importance of the city’s network of public swimming pools, it’s essential to look back at the history of baths as a public health initiative in New York City. The public bathhouse and floating baths in the city’s rivers, initiatives during the City Beautiful movement when indoor plumbing was still a luxury, firmly established the government’s role in providing places to bathe and swim.

In the 1930s and ’40s, the Department of Parks in New York City was given jurisdiction over city bathhouses and the agency “harnessed Works Progress Administration labor to develop a series of outdoor pools for the city,” describes the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation today.

In 1936, 11 pools were opened by Robert Moses, Parks Commissioner, and Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. In total, Moses oversaw the construction and opening of 23 public pools and bathhouses. Some of the WPA-era pools and accompanying buildings are landmarks, including the Art Moderne-style Tompkinsville Pool Bath House in Staten Island and the Sunset Play Center Bathhouse in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Others, including the Astoria Pool, the largest in New York City, are not landmarked but are noted for their cutting edge design. The Astoria Pool, with a backdrop of Moses’ cash cow creation, the Triborough Bridge, is an Olympic-standard size pool that can fit 3000 people.

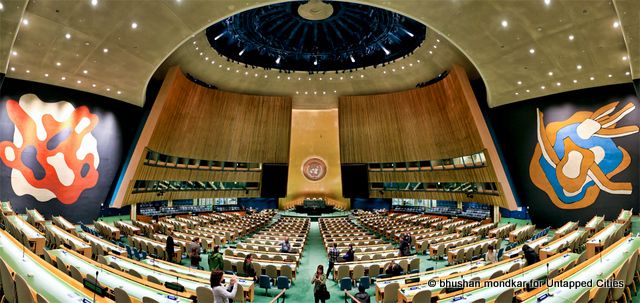

The location of the United Nations headquarters on the East Side of Manhattan was part of a long negotiation process that followed a failed attempt by developer William Zeckendorf, Sr. to build “X City,” a “Dream City” to rival Rockefeller Center. Zeckendorf liked to dream big but was unable to pay off the short term loans on this land parcel.

Behind the scenes, Robert Moses was negotiating for the United Nations to be located on this site in New York City and convinced John D. Rockefeller to buy the 17 acres in 1946. The $8.5 million purchase price is equivalent to $83 million today. Without Moses’ handiwork, the United Nations would have likely been located in Philadelphia.

Fun fact: The United Nations complex is on international territory. Read about this and other secrets in our guide, The Top 10 Secrets of the United Nations.

Robert Moses may have been rather cavalier about uprooting lower-income neighborhoods to put in highways like the Cross-Bronx Expressway but many of his building policies were aimed at fighting suburban flight and keeping middle-class residents in New York City. Even the public pool initiative was intended as a physical manifestation of middle-class values. The New York Times noted in 2007 that “Projects like [East River Park and Riverside Park], in which Moses sought to weave a densely populated metropolis into a broader regional network animated by the freedom of the open road, sprang from a heartfelt populist agenda.”

Stuyvesant Town, though often overshadowed for its exclusionary racial policies (subject to some revisionism and reanalysis a decade ago) and out of context design, provided middle class housing for over 25,000 residents (while requiring the eviction of 11,000 in the former Gas House District). The unique public-private financing became a model for later developments, although Stuyvesant Town is now fully private, with New York City funding for affordable units.

The famous stories of Moses’ dogmatism pervade even Central Park, where he ordered bulldozers to raze a playground next to Tavern on the Green at night, in the face of community opposition. But Moses brought much to the park, which as the New York Times noted in 2007, “was dotted with fetid Hoovervilles” during the Depression. As the Times continues, “When he was appointed city parks commissioner at the height of the Depression…Moses reseeded lawns, planted flowers, repaved walks, transformed the old Croton Reservoir into the Great Lawn and built a necklace of public playgrounds along the edges of the park, as well as ball fields and the Wollman Memorial Skating Rink.”

Spring Creek Park in Howard Beach has the “largest amount of undeveloped land and wetlands in the northern Jamaica Bay area,” according to the NYC Parks Department. We have to thank Robert Moses for these untouched waterfront areas, which he acquired through condemnation in 1938 as part of the development of the Belt Parkway, which included the Shore Parkway. Before this, the area was an illegal dumping ground and host to noxious industrial activities (although city trash is what also filled in parts of Marine Park). The salt march of Spring Creek Park plays host to a diversity of wildlife. Birdlife, including egrets, great blue herons, mallard ducks, pheasants, and wildlife like muskrats, deer and raccoons abound.

In Marine Park, there were grand plans to build a park and athletic facility according to plan that won a silver medal at the 1936 Olympics. But the venture was waylaid by corruption charges within Mayor James Walker’s administration and the plan and ongoing construction at Marine Park became a symbol of the waste, an easy target for new mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, in his quest to clean up New York City and Robert Moses, newly appointed as commissioner of the Parks Department. 5,400 workers were assigned to the Marine Park plan and were said to be mostly lounging around. In addition, Lay was not in a good position with Moses, having repeatedly opposed the master builder’s efforts on Long Island. Moses even had a nickname for him: “Landscaper Lay.” As Thomas J. Campenella notes in the article, “Playground of the Century: A Political and Design History of New York City’s Greatest Unbuilt Park,” the failure to built this park ironically led to the preservation of the natural tidal landscape in Marine Park.

The NYC Parks Department reports that with Moses as Parks Commissioner, the city added “17 miles of beaches, and 84 miles of parkways. Park acreage had increased from 14,000 acres to 34,673 acres.”

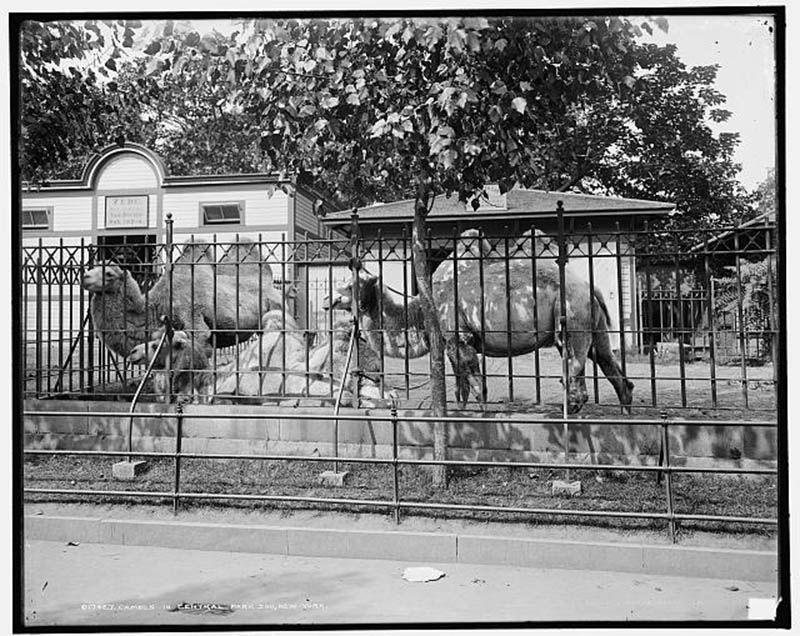

Camels in Central Park Zoo (Image via The Library of Congress)

Robert Moses had a thing for zoos, and thanks to him, the city gained four zoos during his tenure. The renovation of the Central Park Zoo was the most high profile project, with Moses aiming to create more humane conditions at the park menagerie. The design took only 16 days and construction about eight months, with financial support from the WPA. Nine new brick buildings were constructed. The new zoo was the home to gorillas, elephants, lions, bears, and tigers. In the lion house, there were 17 small separate lion spaces and an area to store food. Moses even included a bird hospital. During the renovation, Moses added a restaurant near the sea lion pool but that restaurant no longer exists. When the Central Park Zoo officially opened, Governor Al Smith was given the title of honorary zookeeper, and referred to himself as the “night superintendent.”

Moses was also responsible for creating the Prospect Park Zoo, similarly upgraded from a menagerie, and the Queens Zoo, built in 1968 on the site of the 1964 World’s Fair.

To give you a sense of the number of playgrounds Robert Moses built, there were 119 in the city when he became Parks Commissioner in 1934. In 1960 at the end of his tenure, here were 777. According to the article “The Politics of the Playground” in the academic journal ARQ, “Under Moses’s responsibility, between 1934 and 1960, the city achieved to add an average of one new playground every two weeks.”

Through logical and crafty ways, Moses actively sought to increase the city’s parklands. As the New York Post describes,

Also nearly forgotten are Moses’ efforts as the city’s first parks commissioner to secure its disappearing parcels of open space. When Depression-era playgrounds consisted of empty plots of dirt, Moses would travel around New York to identify and obtain, in imaginative ways, the land we use for recreation.

This included transferring under-utilized city-owned property to his Parks Department, searching property records to discover plots the city forgot it owned, working to forgive back taxes and buying land on the cheap by using money stored in forgotten trust funds and even obtaining grants of church property from Cardinal Hayes.

Next, read the flip side: 5 Things in NYC We Can Blame on Robert Moses.

Subscribe to our newsletter