NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

Edgar Allan Poe’s legacy haunts and compels people all over the world. His greatest impact is felt in the cities where he once lived, which include New York City, Richmond, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Poe was inspired by the culture, architecture, and crime of Philadelphia where he gave birth to the detective genre with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and delved into the human psyche with “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Black Cat.” Poe published 28 other stories and edited Graham’s Magazine and Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine while living in Philadelphia.

173 years after Poe left Philadelphia, his legacy is preserved through the Philadelphia Poe House run by The National Park Service and The Free Library of Philadelphia. People from all over the world come to Philadelphia to study Poe, his accomplishments, his old house, and the publications and manuscripts that live in the Rare Books Department of The Free Library. The top ten Edgar Allan Poe sites in Philadelphia can be explored in these places.

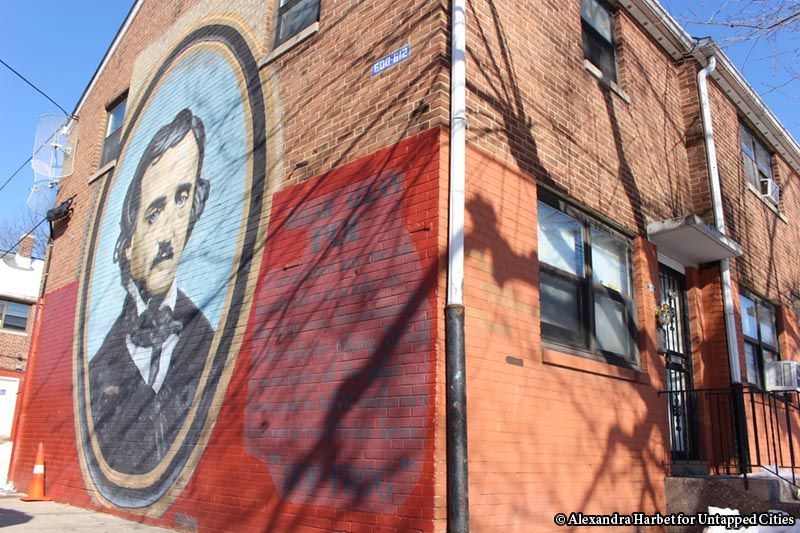

The Poe Mural painted on a neighboring house across the street from the Poe House.

Historical sites in Philadelphia are often accompanied by art in the form of murals. An Edgar Allan Poe mural is painted on a house across the street from the Poe House to honor the man who once lived in the neighborhood.

The mural features an oval portrait of Poe and the passage, “I never knew anyone so keenly alive to a joke as the king was. He seemed to live only for joking. To tell a good story of the joke kind, and to tell it well, was the surest way to his favor.” The excerpt is from Poe’s short story, “Hop-Frog,” which was originally published as “Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs.”

Grip the raven, Colonel Richard Gimbel collection of Edgar Allan Poe, Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.

While touring the Rare Books Department in the Free Library, visitors may notice two beady black eyes following their every move. Those eyes belong to Charles Dickens’ preserved pet raven, Grip. Dickens procured the raven while he wrote Barnaby Rudge, to accurately portray the raven in the novel. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a literary review of Barnaby Rudge in Graham’s Magazine and many believe that Grip is the inspiration for Poe’s, “The Raven.” Grip is on display in the Rare Books Department and visitors can view him without an appointment.

Grip is part of the Richard A. Gimbel Edgar Allan Poe Collection, along with original manuscripts and publications of Poe’s works. Most of the massive collection isn’t openly displayed but visitors are encouraged to make an appointment at least a day in advance to study non-showcased items from the collection. Items must be viewed one at a time in the Reading Room and visitors are asked to make their specific requests when booking an appointment.

A looming raven statue guards the grounds of Edgar Allan Poe’s former North 7th Street home in Philadelphia. Back when Poe lived here with his family, the house was numbered at 234 but it has since been changed to 530.

Poe rented the house from 1842 to 1843 and of his four known houses in Philly, this is the only one left standing. The withering raven is the first thing visitors glimpse before they enter the hallowed halls of Poe’s former home.

Nestled above the entrance to the cellar is a painting by Richard Hood that represents what the house may have looked like in its former glory. At the time, the house was located in a suburban neighborhood called The Spring Garden District which didn’t merge with Philadelphia until 1854. When the three-story roadhouse was built in 1840, the builder had high hopes that the new builders in the area would match the design. At first, the neighborhood fit into the builder’s tract housing aesthetic but once homeowners began putting additions on their houses, the neighborhood lost its cookie cutter look.

Poe’s Spring Garden District was a middle-class suburban neighborhood that was home to two other editors. Houses in the area were equipped with gas, and neighborhood amenities included a railway station, paved streets, running water, and a town watch. Architectural historians removed portions of plaster, mantlepieces, and wallpaper in various places of Poe’s former home to determine what the house looked like when Poe resided there. Rangers will pull out the 1849 maps of the area for interested guests.

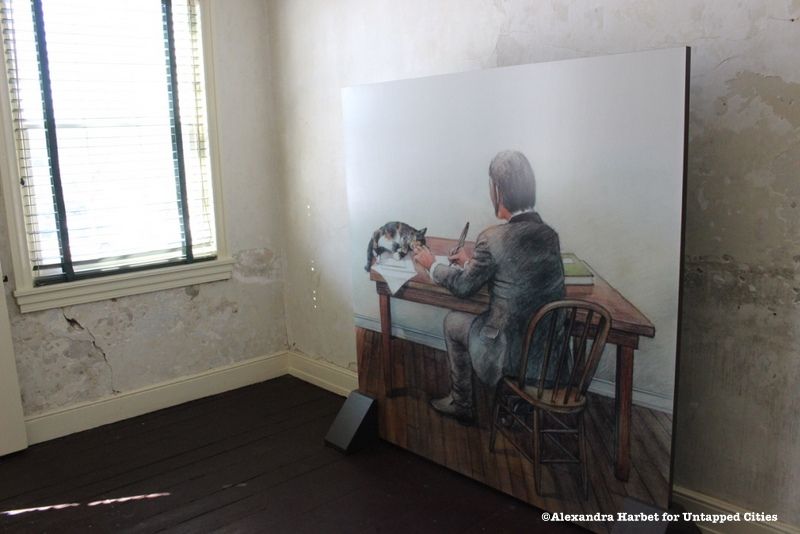

There are no official records to establish which member of the Poe family occupied which room but historians believe that Poe lived in this room on the second floor because the window provides the best natural writing light. Visitors can look at a window painting to see what the view may have looked like when Poe gazed out of the window in the 1840s. He would have smelled the fresh food from the open-air Spring Garden Market across the street and the horses that lived in the stables at Lukens Inn. Virginia was sick with tuberculosis during her stay in Philadelphia which could explain why she and Poe didn’t share a room.

Virginia likely lived in the room on the right on the third and highest floor. Due to her illness, Virginia needed fresh air and quiet. The third-floor room was positioned furthest from the street and the stables and would have provided the calmest environment and cleanest air for the ailing woman. No amount of rest or fresh air was able to cure Virginia as she died in 1847 in Poe Cottage, located in the Bronx, in New York City.

The Poe House’s claim that Edgar Allan Poe wrote “The Raven” in his Philadelphia home is unsubstantiated but plausible, as Poe first attempted to publish an early draft in Graham’s Magazine before he left Philadelphia. The declaration can be boiled down to drumming up business and enthusiasm for the museum when it first opened. It’s not uncommon for historical sites to brag about everything they possibly can and with a subject like where Poe wrote his most well-known poem, the muddied details about how long it took to write and where he wrote it lends itself perfectly to repeated claims.

Untapped Cities covered a story about the other two conflicting plaques in New York City that also claim to have housed Poe while he wrote “The Raven.” While the location or locations where Poe wrote “The Raven” are hotly contested, the previously missing Raven Mantle was located by Untapped Cities and can be found at Columbia University.

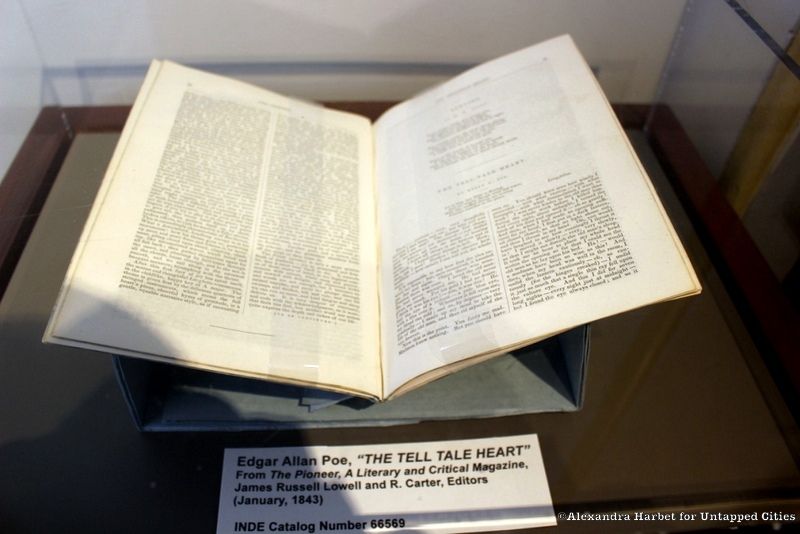

While most of Poe’s historical documents in Philadelphia can be found in The Free Library, the 1843 publication of The Pioneer sits proudly on display in the Edgar Allan Poe House. The magazine is flipped to Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” which he published while living in Philadelphia. Poe’s original publications are hard to come by given how long ago they were published. Original manuscripts are even rarer and in many cases, no longer exist.

Back in the 1800s, it was common for printers to throw out original manuscripts after they were printed for publication. Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” almost suffered that fate but was saved by a printer’s devil (a printing apprentice) at Graham’s Magazine at the last minute. J. M. Johnston requested to keep the manuscript and fished it out of the trash without knowing that his effort would help preserve a famous writer’s legacy. Because of the passion of an apprentice in the 1840s, an original manuscript of the first detective story exists in the Richard Gimbel Collection of Edgar Allan Poe in the Free Library’s Rare Books Department.

The false chimney in Poe’s old cellar.

As visitors descend down the stairs to the cellar, they are met with chilled air and an ominous feeling. The cellar permeates with Edgar Allan Poe’s presence and the horror that inspired his grim tales. His short story, “The Black Cat” comes to life when guests look at the false chimney that mirrors the one the narrator uses to wall up his victims.

When tiptoeing around the musty cellar with its cobwebs and dark crevices, it’s hard not to contemplate the mysteries surrounding Poe and whatever secrets are still hidden in the false chimneys of his life.

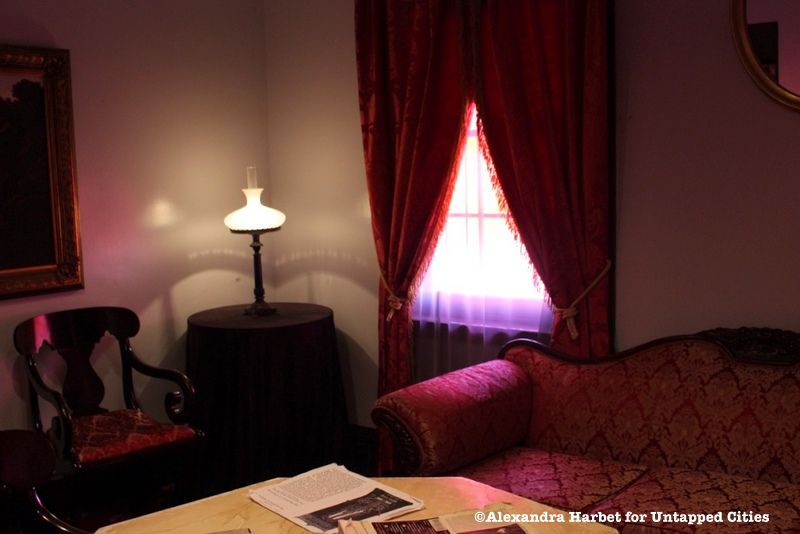

The Reading Room in the Poe House is furnished to emulate his satirized description of rich middle-class decorations in “The Philosophy of furniture.” Poe wrote the essay to make fun of the newly rich and how they spent their money on gaudy decor.

With the ambiance of the dim lighting and surprisingly plush couches, the mockery is lost on visitors as they enjoy reading the massive collection of Edgar Allan Poe’s works, encyclopedias, and biographies or listen to the many renditions of his works in this fancy, old- fashioned room.

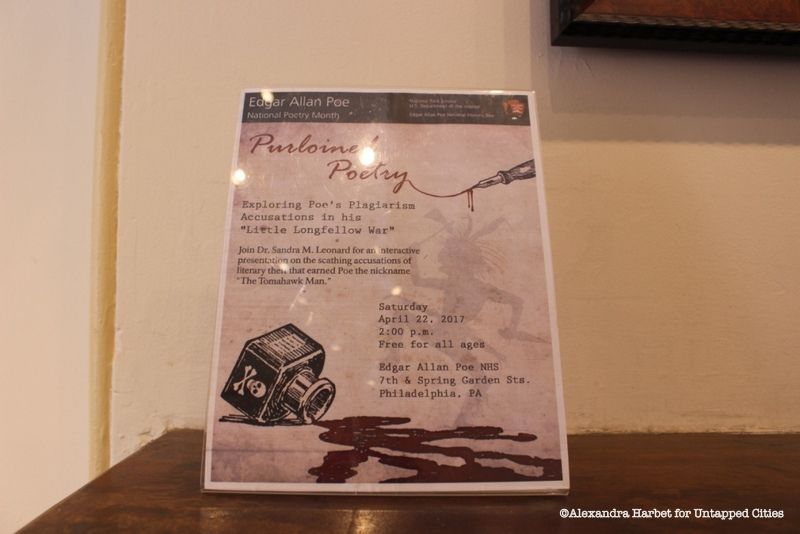

Philadelphia embraces the history of the city and the historical figures who once called it home through events and educational discussions. The Poe House will have a Purloined Poetry Discussion on April 22nd that will cover Poe’s plagiarism allegation against H.W. Longfellow.

Past Poe events in Philadelphia include the Poe Arts Festival that took place in October of 2016 and the Poe House’s Women’s History Month tour that occurred earlier in March. To stay up-to-date on all of the Poe happenings in Philadelphia, bookmark the Edgar Allan Poe National Park Service’s page and the events page on The Free Library’s website.

The Spooky window view from Poe’s cellar

A huge thank you to the immensely helpful Rangers Cosgrove and Schillizzi who provided us with enough information to write ten pages of notes. A shout out also goes to the lovely folks at the Rare Books Department at The Free Library of Philadelphia for their assistance.

Next, check out 9 Places to Remember Edgar Allan Poe in NYC and In Search of Edgar Allan Poe in NYC. Get in touch with the author @LitByLiterature.

Subscribe to our newsletter