The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

Few biographies are as cleanly suited to the David vs. Goliath, Batman vs. Joker, good vs. evil narrative of opposition as that of Jane Jacobs, the urban writer and activist, and her almost Hollywood-perfect antagonist, urban planner Robert Moses.

Matt Tyrnauer’s new biographical documentary “Citizen Jane: Battle for the City” (out now at IFC Center) is primarily concerned with Jacobs – the journalist, mother, and reluctant activist. But it’s almost impossible to tell her story without frequent mention of Moses. Her outrage would have no target if not for his bold, totalitarian designs for the city. And the 20th century history of development in New York City is largely a story of Jacobs vs. Moses.

Tyrnauer begins and ends his film with cautionary sequences highlighting the rapid pace of urbanization taking place around the globe today, especially in the developing world. The challenges of pollution, overcrowding and inequality that so worried New York progressives in the first part of the 20th century would be familiar to planners of China’s cities today.

In Tyrnauer’s telling, the Great Depression in particular transformed how New Yorkers viewed the urban condition. Dirty, coal-choked streets and slums packed with immigrants and criminals didn’t mesh with the futuristic, efficient vision of the city epitomized by such gleaming newcomers as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building.

Moses began working in this era, and his professional life can be read as a long, stifling knee-jerk reaction against these forces he saw as threatening the American way of life. Like the turn-of-the-century progressives before him, Moses felt the solution to the ills of crowded, filthy cities was to wipe the slate clean. Where Jacobs saw a healthy human ecosystem in the form of sidewalk culture and immigrant innovation, Moses and his ilk found a problem to be solved, a blight on the city, a failure of the modern machine age. We even see him recite to an interviewer at one point the old quip “”you can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs.”

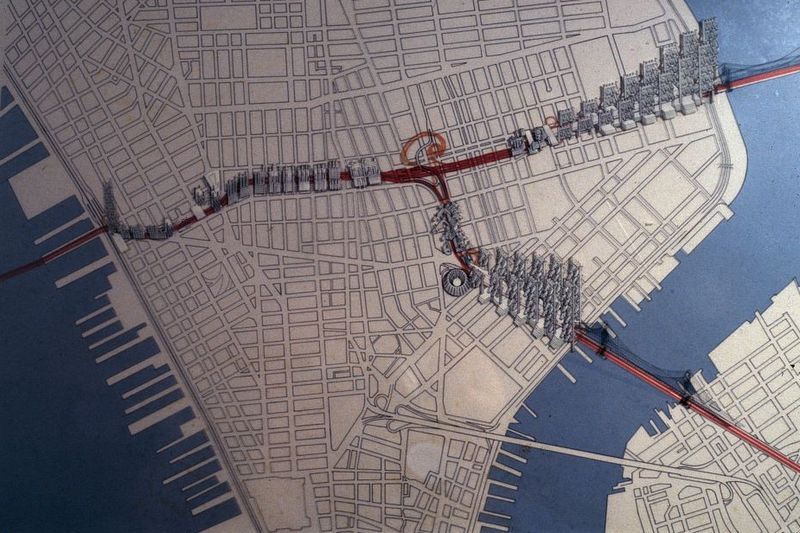

Proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) that would connect the East and Hudson River crossings. via Library of Congress.

The film makes frequent use of commentary from architects, planners and urban thinkers, many of whom will be familiar to fans of Jacobsian urbanism: Alexander Garvin, Paul Goldberger, Michael Sorkin, Mary Rowe, James Howard Kunstler, and Saskia Sassen. We are also treated to frequent archival footage showing Jacobs and Moses actually speaking – a rare treat for two historical heavyweights we’re so used to experiencing solely on paper. And Jacobs was able to use the new mediums of film and television to amplify both her message and her magnetic personality; Moses probably underestimated the degree to which his monotone ruthlessness on camera unsettled viewers.

To Jacobs, who moved to New York as a young woman from her hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, the city was the ultimate iteration of the vital, messy, modern patchwork of humanity. She found it, like so many young newcomers before her and since, pulsing, life-giving, and “inexhaustible.” And like so many writers before her and since, she became obsessed with capturing its singular energy on the page.

Moses and Jacobs were the Goliath and David of 20th century New York City development. Photo from Wikimedia Commons from Library of Congress.

Moses and Jacobs were the Goliath and David of 20th century New York City development. Photo from Wikimedia Commons from Library of Congress.

Jacobs published The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the tome for which she would most be remembered, in 1961. A commentator in the film compares it to Martin Luther’s nailing of his 95 Theses on the church door – a sacrilegious break from the accepted city planning orthodoxy. The power players in New York City government and planning were all men, and Jacobs was dismissed as a bored housewife who had no authority to comment on big boy concerns like the design of cities.

But it was precisely Jacobs’ outsider status that allowed her to identify so keenly the foibles of modern urban development. She was first and foremost an observer – an observer of the delicate sidewalk dance that occurred when people of diverse backgrounds, ages and professions converged on busy streets, an observer of the physical traits that most cultivated human interaction (short blocks, walk-up apartments and street-level retail), and an observer of how these conditions were being threatened by novel city-building strategies.

The “expert” urban planners that were the subject of her criticism were seemingly blind to observation – instead they were theorizers. And the theory that was in vogue at the time was that cities could be mass-produced just like Henry Ford and his manufacturing revolution had done to the automobile and other consumer goods. Moses imported wholesale the Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s tower-in-the-park housing typology, and exploited it to such an extent that it was replicated by urban housing agencies across the United States.

The low-scale, mixed-use nature of Jacobs’s beloved West Village largely informed her view of cities

The low-scale, mixed-use nature of Jacobs’s beloved West Village largely informed her view of cities

Of course Jacobs was a theorizer as well, and not just of what makes a city robust and fair, but also of how best to fight her fight. She really began to develop a strategy of opposition in the face of a Moses plan that would hit uncomfortably close to her West Village home – a 1952 proposal to shove Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park. Jacobs organized a “ribbon-tying ceremony” at the park as a cheeky response to the ribbon-cutting ceremonies that were becoming popular photo ops for city officials. Her daughter and another young girl were featured in TV news shots, and Eleanor Roosevelt delivered a speech in support of their cause.

As commentators in the film point out, Jacobs’s cause owed much to the larger wave of resistance to central authority that crested to a fever pitch in the 1960s. Feminism, environmentalism, and civil rights all “shared tools” of organizing and civil disobedience. Moses wasn’t used to opposition. The power he had amassed over the years as the parks commissioner, highways commissioner, urban renewal czar, head of the mayor’s committee on slum clearance, and chairman of the housing authority and Triborough Bridge Authority came without a single popular vote.

The city’s Board of Estimate voted against the Fifth Avenue reroute in a riveting televised debate captured in the film, handing Moses his first major defeat. Death & Life would be published soon after, and Moses would return the complementary copy sent him by the publisher with a terse note claiming libel. As if as revenge, Jacobs’s cherished West Village was targeted for urban renewal soon thereafter. Jacobs would claim another success there, followed by a devastating setback in the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, and one final, resplendent victory in the cancellation of plans for a Lower Manhattan Expressway.

The Lower Manhattan Expressway marked the beginning of the end for Moses – it awakened city-dwellers to the ravages of high-speed automobile rights-of-way in their backyards, and sparked a nationwide “freeway revolt.” Not long after, cities began to recognize the unforeseen outcomes of concentrated poverty and endemic crime in the tall brick housing projects they had built with such fervor just a couple decades earlier.

As Jacobs fan celebrate the centennial of her birth this year, “Citizen Jane” is a potent reminder that the Moses-Jacobs battle for the city hasn’t been won decisively by either side. While Jacobs’s vision of the city has been largely credited for a resurgence of interest in city living in the United States, especially among young people, the actual planners behind cities the world over still bear a closer resemblance to Mr. Moses. While Tyrnauer’s film is unlikely to change the minds of (or even be seen by) latter-day Moses-style city builders, for the rest of us, it’s a useful telling of how we got where we are, and what it takes to fight for the kind of city we want to inhabit.

Next, check out the 5 Things We Can Blame on Robert Moses, 8 Things We Can Thank Him For, and the NYC apartments that Jane Jacobs lived in.

Subscribe to our newsletter