Behind the Curtain Wall w/ NYC Architect Richard Roth Jr.: Alexander's

Discover an unlikely friendship that emerged from the design of a lost NYC department store!

Columbia University in Morningside Heights was founded as King’s College in 1754 by King George II of England. Its first graduating class had only eight people who attended class in a small schoolhouse adjoining to Trinity Church. The fifth-oldest university in America and the oldest in New York, Columbia educated some of the soon-to-be United States’ most seminal revolutionary minds including Alexander Hamilton.

It is the largest single collection of designs by McKim, Mead, and White, who modeled the buildings in a Roman classical style. Columbia is worth a visit for anyone interested in classical architecture, but there is a lot more to it than meets the eye. Sure, you could sit on Low Steps and people-watch, but if you’re an Untapped Cities reader you most likely are interested in some more unique adventures. Countless secret haunts and stories line the labyrinthine campus, which stretches far underground through tunnels and high up to the tops of buildings. Read on to discover 10 off-the-beaten-path things to do (some easier than others) at one of the world’s most famous and controversial institutions.

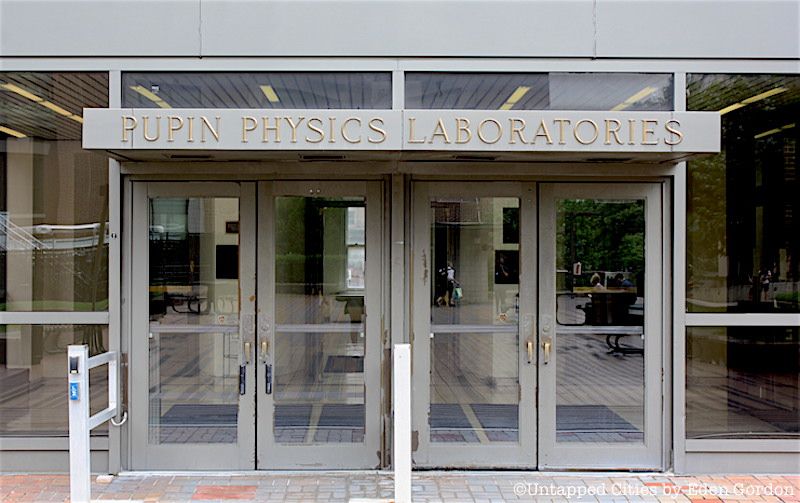

Much of the research for the Manhattan Project—which developed the nuclear bombs that would later fall on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II—was conducted at Columbia University. A significant amount occurred in the basement laboratories of Pupin Hall, which was home to the Nevis cyclotron, a type of particle accelerator known as an “atom smasher” that could channel atoms through a vacuum at a speed of up to 25,000 miles per second. This machine eventually helped a team of scientists replicate German discovery of nuclear fission, and aided the United States in developing nuclear bombs.

Not much of the experiment is visible to the cautious explorer, but anyone can pay a visit to the plaque on Pupin’s foyer, which declares the hall a National Historic Landmark and a place of “exceptional historical value.” Notably, the plaque does not mention nuclear fission or any of the experiments that occurred inside. Still, the hall is worth a visit, if only to contemplate the tremendous significance of the experiments that occurred just below the surface.

If you’re a more adventurous sort, Pupin’s basement connects to the Columbia University tunnels. Though their presence is well known, few have ever explored their full extents. The tunnels are relics from Columbia’s days as the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, and they also connect to Buell Hall, the last remaining relic of the mental institution. Apparently, the cyclotron used to create the Manhattan Project’s nuclear arsenal is still down there somewhere.

During the 1968 student strike, WKCR students used the tunnels to tap into the university’s telephone system. The tunnels were also the location where much of the research for the Manhattan Project was completed and stored. Though it was removed in 2008, the old cyclotron, instrumental in developing nuclear technology and apparently still putting out gamma rays, allegedly still remains somewhere in the tunnels, a haunting relic of the past. Many of the tunnels have been closed since the 1980s, when a university student named Ken Hechtman founded a group called AD HOC that dedicated itself to causing trouble and infiltrating the tunnels. During the brief period when AD HOC existed, Hechtman and others stole uranium and other dangerous chemicals, and his antics had him named a campus legend. Hechtman was later expelled, but the intrigue of the tunnels has never faded.

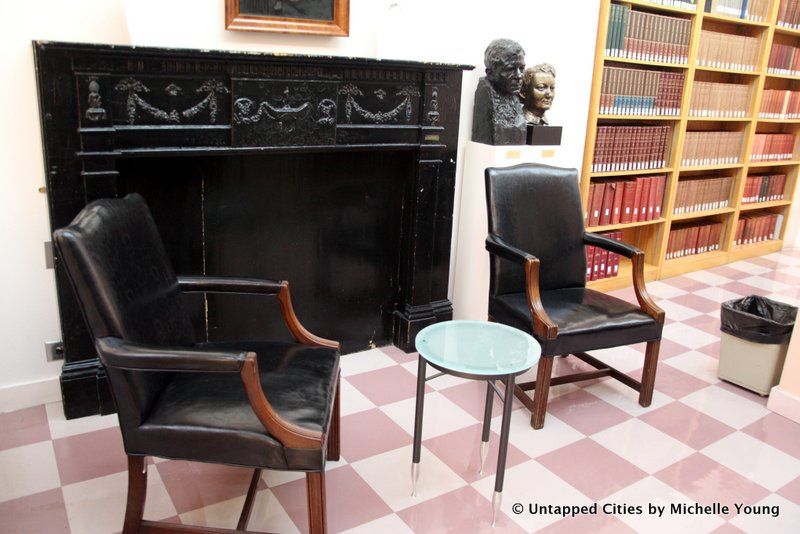

In 2012, Untapped Cities writer Benjamin Waldman discovered a long-hidden treasure: the mantlepiece next to which Edgar Allan Poe wrote his seminal poem, “The Raven.” Presented as a gift to Columbia on January 4th, 1908, the mantle was soon forgotten and lost to public knowledge. Columbia’s archives are unclear about where it was kept over the next forty-0dd years: some report that it was in Philosophy Hall, while others state it was kept in Low Library. Eventually, it ended up in a storage area in Butler Library, its black paint chipping, mostly unknown.

Though it was physically lost, its legacy lived on in words. The poem mentions the fireplace in the line “each separate dying ember / Wrought its ghost upon the floor.” When Columbia received the mantle, then-president Nicholas Murray Butler promised that the mantle would be preserved and displayed in a prominent place—but the distortions of time led to the mantle’s relegation to the shadows of Butler Library. Since being discovered, it has been moved to a more easily accessible location in Butler’s Rare Books and Manuscript Library, and can be found there today.

In 1914, Columbia’s senior graduating class presented the university with a gift: a sixteen-ton granite sundial, placed atop a base with the inscription, “Horam Expecta Veniet,” or, “await the hour, it will come.” Each day at noon, the sphere cast a shadow and marked the date. The sundial was a meeting place and a central presence on campus.

At one time, the sphere was believed to be the largest piece of granite on Earth. However, in the winter of 1946 the stone began to crack, and the sphere was removed. It was believed that it was brought to a Bronx stoneyard and destroyed. In 2001, nearly 60 years later, an art curator contacted the university and told them that the sphere was in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where it remains today, mystifyingly brought there by an unknown person affiliated with Columbia.

Better known as St. A’s, this building – located on Riverside Drive between 116th and 115h streets – is home to the alpha chapter of the Delta Psi fraternity, which brands itself both as a secret society and as a literary society. Most Columbia students view the fraternity as a selective organization that selects particularly wealthy students and prides itself on secrecy. St. A’s hosts frequent invitation-only parties.

If you’re lucky enough to nab one, St. A’s Riverside Drive location’s most commonly photographed attraction is a chandelier displayed on the cover of Vampire Weekend’s self-titled debut album. (The members of Vampire Weekend met while attending Columbia in the mid-2000s).

The organization, which now includes a sorority, has existed since 1897. Its current Riverside Drive location was built in 1899. The building was designed in a Beaux-Arts style by Henri Hornbostel.

Several controversies and rumors have swirled around the organization. It is suspected that the basement of St. A’s houses a swimming pool, though some have also speculated that it is inhabited by a maid who does the group’s laundry. It was also the model for Gossip Girl’s elite Hamilton House. Another rumor about the fraternity and sorority’s antics suggests that there is a hazing requirement that forces potential recruits to purchase a plane ticket to China and then burn it.

Although you’ll probably need a few connections to actually go inside St. A’s, the building is conveniently located next to the very beautiful Riverside Park.

Columbia’s very own Whispering Bench was donated by the class of 1886 on its 25th reunion. Inside the semicircle, the world grows almost silent, and you can hear someone speaking in a low voice from the other side of the bench.

As Untapped Cities editor Samantha Sokol describes, “It’s amazing when you’re sitting in it, the acoustics are totally different. It sounds like you’re in a tunnel, or your ears are clogged. My friend and I had a quiet conversation on opposite sides of the bench. Once I stood up, I couldn’t hear a thing she was saying.”

The bench is located between St. Paul’s Chapel and Low Library. Its inscription reads, “To Fellowship and Love of Alma Mater, Class of 1886 Arts, Mines, Political Science: 25th Anniversary.” The Mines is in reference to the fact that what is now the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, was originally called the School of Mines.

Columbia University’s math building, located around 118th and Broadway, is adorned with a plaque that commemorates the Revolutionary War battle that took place at the university. Columbia was the location of the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776. After the British defeat and retreat from Long Island, George Washington led outnumbered American troops to a victory over advancing British forces. The battle was the first victory of the New York campaign, and offered a critical boost in American morale.

Seeking a coffeehouse-music venue located underneath a church? Look no further than Postcrypt, Columbia University’s very own underground (literally) folk music hub, located in the basement of St. Paul’s Chapel. The coffeehouse hosts established and emerging acts and also offers monthly open mics. Past performers have included Jeff Buckley, Dar Williams, Suzanne Vega, and more.

Admission is always free, and the music isn’t confined to the folk genre: plenty of country, blues, rock, poetry, and everything beyond or in between can be heard passing through the ‘crypt on any given night.

Postcrypt hosted its first annual music festival on the Columbia lawns this year. It will reopen for the fall season in September.

A new sculpture came to live on Columbia’s campus in 2015. Reclining Figure, a sculpture by Henry Moore, was set to be installed directly in front of Butler Library. However, stymied by student protests, the sculpture was ultimately moved to a more secluded location on a green near the Northwest Corner Building on the campus’s northwest side.

Protests focused mostly on Reclining Figure’s aesthetic “ugliness” that they believed did not fit in with the university’s neo-classical aesthetic. The sculpture has been described as anthropoid and pterodactyl-esque, and students feared it would disrupt the harmony of Butler’s picturesque façade. However, others supported Reclining Figure’s unique qualities, overt femininity, and modernist design, believing it would represent a step forward in a university often mired in the murk of its past. (The front of Butler Library, for example, is printed with the names of seminal Greek thinkers—not exactly the most diverse bunch).

Columbia University’s Alfred Lerner Hall was designed by deconstructivist architect Bernard Tschumi, and features a glass wall facing campus designed by Eiffel Constructions Metalliques, a descendant of the firm that designed the Eiffel Tower. With its convoluted, labyrinthine web of staircases, and frequently illuminated by fluorescent lights supporting one cause or another, the building is a remarkable and occasionally disorienting experience.

It was created to be a meeting place for students as well as a home for the mailroom, back in the days before mail came on paper instead of via email or instant messaging, but now its vast array of mailboxes is a kind of ghost town, a silent room broken only by the odd student wandering in to collect their Amazon package. In spite of this, Lerner Hall is still a vibrant hub of student life. It is home to several noteworthy venues, including the brand-new CU Records, a student-operated recording studio located on the fifth floor. The studio was founded by university students and is currently free to use for any musicians, including non-students.

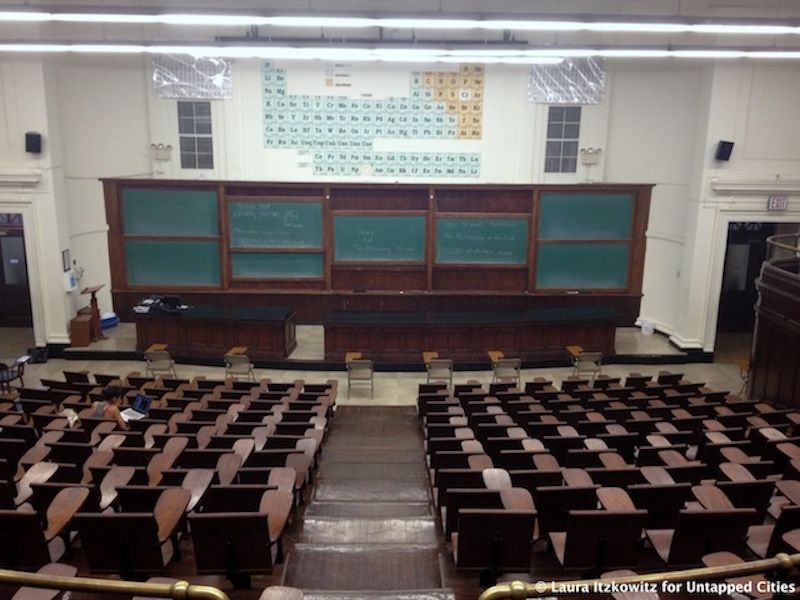

Havemeyer Hall is one of Columbia’s oldest buildings, and also one of its most famous—one of its classrooms, Room 309, has been featured in more movies than any other university classroom in the US.

It was built between 1896 and 1898 under the supervision of Charles Frederick Chandler II, an instrumental founder of Columbia University’s chemistry department. One of the school’s six original buildings, Havemeyer Hall’s distinct limestone-frosted red brick layout was designed by McKim, Mead, and White. The building is now home to the university’s chemistry department, and it has hosted research that has led to seven Nobel prizes. Room 309, the central lecture hall, has appeared in nine major motion pictures, including Ghostbusters, Spiderman, Mona Lisa Smile, and Kinsey.

Did you know that Columbia has its own art gallery? Formerly Tucked away in Schermerhorn Hall but now at the new Lenfest Center for the Arts building in the Manhattanville campus, the art gallery that boasts exhibitions curated and featuring some of contemporary art’s most promising newcomers. It displays exhibitions that are curated by art history and archaeology graduate students at the university.

One of the most magical things about New York City is the way that so many tiny gardens pockmark its steely, industrial streets. In this tradition, on the corner of 111th and Amsterdam Avenue, the buildings break open for a second, and a small patch of greenery can be seen by the keen eye or knowing visitor. The West 111th Street People’s Garden, located at 112th and Amsterdam, is a lesser-known but very tranquil piece of landscaping that frequently provides a necessary respite for stressed-out students or any keen-eyed passersby.

Its location next to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine provides an alluring backdrop to accompany its tranquility. One of the garden’s highlights is the Peace Fountain, a 1985 sculpture depicting the battle between good and evil. With its rambling, charmingly unkempt wildflowers and its stone benches, this is a place worth visiting, if only to take a moment to reflect and breathe.

In celebration of its 30th anniversary, The Broadway Mall Association, in collaboration with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, and the Morrison Gallery of Kent, Connecticut commissioned the new installation, Joy Brown on Broadway. The nine large, charming bronze works rest on the Broadway malls from 72nd Street to 168th Street, greeting pedestrians crossing the street, and subway riders emerging from below ground. The gentle giants will remain on view through November, 2017.

This one, located at 117th and Broadway, seems to take after the aforementioned Reclining Figure rather than the imposing, classically beautiful statues that have historically populated Columbia’s campus. The figure looks lovable and soft, and seems like a friendly face amidst Broadway’s traffic.

Joy Brown is influenced by her childhood in Japan, and her apprenticeship in traditional Japanese wood-fired ceramics. She has exhibited in galleries and museums in the United States, Europe, and Asia. In 1998, she co-founded Still Mountain Center, a nonprofit arts organization that fosters East-West artistic exchange.

If you happen to be in Morningside Heights on a sunny Thursday or Saturday, you can stop by the local farmer’s market for a chance to snack on some fresh apples, baked goods, lemonade, and more. The market also offers several opportunities to do some good for the planet: GrowNYC hosts a clothing collection from 8:00 AM to 3:00 PM, and a food scraps compost open from 8:00 AM to 1:00 PM. Vendors sell anything from food to clothes to jewelry to electronics.

Known for being extremely crowded and somewhat pricey, Joe Coffee also is known for selling excellent caffeinated beverages. So climb up the Northwest Corner building and sip some of the best joe in New York City. Joe’s signature blue cups are often seen in the hands of students and professors.

Joe is located on the second floor of the Northwest Corner building, the towering skyscraper on the—you guessed it—northwest corner of the campus, and the South East corner of the 121st street intersection. If you can get someone with swipe access to the upper levels to let you in, the top floors boast amazing views of the city.

The unmistakable centerpiece and face of Columbia, Low Library was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1991. It was built by then-university President Seth Low. The library was designed in a neoclassical style, loosely based on Rome’s Pantheon. Its windows are modeled after the Baths of Diocletian. Its entryway boasts busts of Athena, Zeus, and Apollo.

Though not exactly an off-the-beaten-path destination, Low has some history of occupation that Columbia would certainly like to keep under the radar. During 1968 protests, students occupied Low, barricading themselves inside the building. Still, news sources like WKCR, the radio station, and the Columbia Daily Spectator were able to report from the inside, leading to suspicion that students were reaching the building through Columbia’s legendary tunnels. (This was before the cell phone era).

In what felt like an echo of protests past, 35 students from Columbia Divest for Climate Justice occupied Low for five days in April 2016. The group advocates for Columbia’s divestment from all fossil fuel companies, 200 of which fund a large part of Columbia’s endowment. Students sat outside the current president Lee Bollinger’s office, and the university eventually put a lockdown on the building, drilling windows shut, putting an end to food supply, and preventing more students from entering. The students who remained were threatened with suspension, and received support in Tweet form from ex-presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Eventually, the university president agreed to speak to the students. In March 2017, Columbia announced its divestment from thermal coal companies, though it continues to receive funding from other fossil fuel behemoths.

Got a problem with how Columbia’s being run? You’re not alone—and Low is a great place to make your opinions known.

For more, check out The Top 15 Secrets of Columbia University in NYC and 15 Must-Visit Places in Morningside Heights, NYC: An Untapped Cities Guide.

Subscribe to our newsletter