See the Original Manuscript of Kafka's 'The Metamorphosis' at The Morgan Library

Join a guided tour of a special exhibit on Franz Kafka featuring artifacts never displayed in the US!

Downtown Brooklyn is a commercial and cultural hub as well as a residential neighborhood, but it also harbors a number of unexpected secrets. On its way to becoming the cosmopolitan mecca it is today, the neighborhood experienced a chaotic history that can still be found written in its streets and floating around in the air.

For more, check out Untapped Cities founder Michelle Young and Augustin Pasquet’s Secret Brooklyn, on sale now, and read on to discover the secrets and stories of the crux of Brooklyn.

Downtown Brooklyn might mostly be a pleasant residential and cultural hub, but it is also home to a functioning prison. Located at 275 Atlantic Avenue, the Brooklyn Detention Complex can hold up to 815 male inmates.

Its origins stem from the depths of the seedy tangle that is New York City bureaucracy. Built in the 1950s, the prison closed in 2003, but to fund its renovation, ex-city comptroller Bill Thompson allegedly cut a deal with City Hall, approving a $34 million renovation project. In exchange, the city dropped the lawsuit that had been raised against him. Once adequately funded, the prison reopened in 2012. Some prisons are physical and others are capital. This detention complex is both.

New York City was home to many important abolitionists, and Brooklyn especially was an active hub of abolitionist activism in the 1850s and 60s. Many Downtown Brooklyn houses and churches functioned as safe houses on the Underground Railroad during this time. In 2007, Duffield Street was renamed “Abolitionist Place” by the City of New York. Buildings believed to be safe houses include 223, 225, 227, 231, 233, and 235 Duffield Street, in addition to the African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church located in MetroTech Center.

Plymouth Church, located on the border between Downtown Brooklyn and Brooklyn Heights, is an especially important landmark: Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, began preaching there in 1847, and invited important figures including Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Charles Dickens, and Walt Whitman. Later Martin Luther King, Jr. would recite early versions of his “I Have a Dream” speech there. The church also has a piece of Plymouth Rock on display.

Walt Whitman worked at the Brooklyn Eagle in the mid-1800s, but he lost his job due to his support for the Wilmot Proviso, a bill that proposed banning slavery in America’s newly acquired Mexican territory.

During his time with the magazine, Whitman argued for the opening of more green public spaces, and eventually successfully appealed for the creation of Fort Greene Park. Today, in his honor, you can embark on a Walt Whitman walking tour of Fort Greene Park. The poet and icon also spent time in Green-Wood Cemetery, at the Brooklyn Navy Yards, and more.

Brooklyn’s future is looking up—1,066 feet up, that is. Renderings for a bona fide skyscraper, to be built starting in 2019, have been released. The skyscraper is going to be 73 stories and 1,066 feet tall, making it twice the height of the borough’s current tallest structures. Its developers are JDS Development Group in tandem with Chetrit Development, who are able to build such a tall building because they purchased the neighboring Dime Savings Bank and its 300,000 feet of air rights for $90 million in 2015.

The building’s designers are SHoP Architects, who designed the nearby Barclays Center and several Pacific Park/Atlantic Yards buildings. The new skyscraper, located at 340 Flatbush Avenue, will be built from a combination of white marble, bronzed metal, and blackened stainless steel, and its design is a tribute to the historic Dime Savings Bank, part of which will have to be demolished so the skyscraper can be constructed. It will house 417 rental apartments and its base will be used for retail.

The building has had mixed reviews: some see it as a marker of progress for Brooklyn, and others see it as an ominous sign of “Manhattanization.”

People have always been eager to jump on the latest health craze, and in the late 19th century, that craze was the newly minted electric bath cure. In 1900, the first electric bath house appeared at 168 Sylvan Street in downtown Brooklyn. Sylvan Electric Baths promised cures for rheumatism, gout, sciatia, and more. Their advertisements explained that the hot baths opened up pores, allowing toxins to leave the body.

Essentially, these baths were early hot tubs. At the time they were considered miracle cures, and the business became so lucrative that Sylvan Electric Baths expanded to 180 Schermerhorn Street, setting up shop in a three-story bath complex designed by architect William P. Tuthill. The baths catered especially to women suffering from diseases grouped under the umbrella term “hysteria.”

After a few unfortunate incidents, including one suicide in one of the baths by a terminally ill woman and a lawsuit from a man whose legs were burned during a heat treatment, the bath factory closed. Today, 160 Schermerhorn Street is an apartment complex.

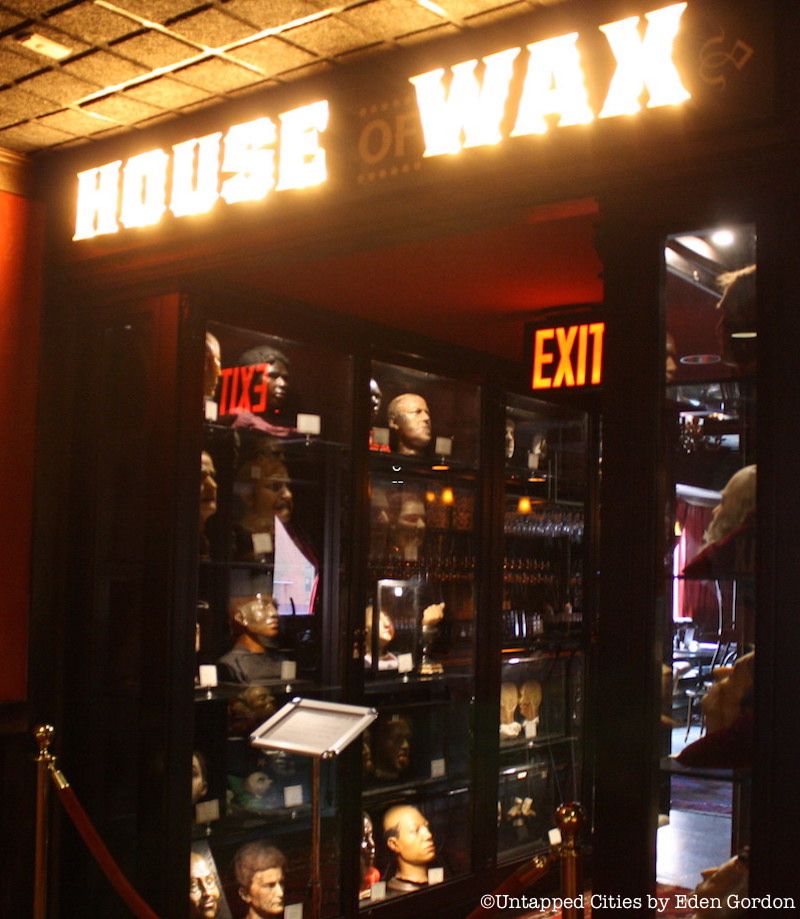

It rises, like an apparition from the night: a glowing sign, lit up with carnivalesque lightbulbs, reading simply, “House of Wax.” Below the lights, gloomy faces stare out of glass cabinets, at once warning you away and daring you to enter.

This is the entrance to one of Downtown Brooklyn’s creepiest locales. Located in the back of Brooklyn’s City Point mall, in the lobby of the newly opened Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, this is one of the strangest bars you’ll ever have a drink in. It houses 100 anatomical models, 25 death masks, and wax depictions of various diseases and mutations. On display are wax busts of fetuses and women giving birth, tumor-riddled tongues, and other sensational objects including a figure of a woman whose organs have been distorted by years of wearing a corset.

This collection is reappearing nearly a century after its last time in public. Originally, the figures were displayed at Castan’s Panopticum, a Berlin museum that closed in 1922. Since then, they were kept in deep storage until they were purchased by Tim League, the CEO of Alamo Drafthouse.

Castan’s Panopticum was eerie and off-kilter even during its heyday, and was probably frequented by late 19th century goths. It has, amidst other illustrious attractions, a full-body bust of the serial killer Fritz Haarmann, also known as the “Butcher of Hanover.” At the “House of Wax,” for $13, you can order your very own “Butcher of Hanover”—a mixed drink.

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

Photo from inside the now defunct Atlantic Avenue Tunnel. Photo by Vlad Rud via Wikimedia Commons

The Atlantic Avenue subway tunnel is the oldest in New York. It was originally built in the mid-19th-century to combat excess aboveground traffic from the Long Island Railroad. Cornelius Vanderbilt, head of the LIRR, decided to build the tunnel, and thus the modern subway system was born.

The tunnel took about seven months to build, and was constructed with a cut-and-cover method: workers cut into the tunnel, covered it with a wood frame, and fortified it with bricks. There was even a murder that took place during the tunnel’s construction, which occurred when one of the workers shot a contractor who told them they could not take Sundays off work. The body apparently still rests in the subway walls. The tunnel was shut down in 1859.

Walt Whitman, who lived in the area, ruminated on the tunnel, writing: “The old tunnel, that used to lie there underground, a passage of Acheron-like solemnity and darkness, now all closed and filled up, and soon to be utterly forgotten.”

But it was not forgotten. In 1980, a 19-year-old student named Bob Diamond heard a rumor that John Wilkes Booth’s body was buried in the Atlantic Avenue tunnel. Fascinated, he began to hunt the body down, searching through old records. He eventually stumbled upon the plans for the tunnel, managed to locate its abandoned ruins, and was put in charge of it, in a rapid-fire series of events that shows just how fruitful urban exploration can often be. Diamond hopes to someday see trains running through the tunnel once again, but for now, it remains a mysterious relic of transportation past.

Downtown Brooklyn hosts the Brooklyn edge of the Manhattan Bridge. This area, often called RAMBO (Right Around the Manhattan Bridge Overpass), was recently graced by the presence of two imposing, quite literally statuesque women. The sculptures, named “Miss Manhattan” and “Miss Brooklyn,” were originally built in 1900 by the sculptor Daniel Chester French, and both were modeled after the famous Audrey Munson, who also provided the inspiration for “Beauty” at the New York Public Library and “Civic Fame” atop the Manhattan Municipal Building.

The statues were removed by Robert Moses in the 1960s and since then have remained in the Brooklyn Museum. In 2011, a $450,000 renovation project facilitated the creation of two exact replicas of the statues, which were installed by the sculptor Brian Tolle. The new sculptures are equipped with LED lights and rest atop a post, greeting visitors as they make the trip from Manhattan to Brooklyn and back.

In 2016, conceptual artist Spencer Finch created a to-scale replica of 4,000 redwood trees, which he placed in Downtown Brooklyn’s Metrotech area. The installation, called “Lost Man’s Creek,” was developed for Brooklyn’s Public Art Fund.

The installation is a 1:100 scale replica in miniature of a 790-acre redwood forest in Redwood National Park. Finch will be cutting the trees to maintain their proportions each year, keeping them at about one to four feet tall. The trees will be on display through March 2018.

The New York Transit Museum is a tribute to the MTA, and a visit might make you think twice before you complain about the subways’ defunctness. Planning New York City transit is a big job, and this museum is a homage to the people who put their blood, sweat, and tears into creating the tracks and trams that move us all over the city.

In addition, on the museum’s lower level there is an extensive collection of old subway cars, dating back to the early 1900s. The cars boast vintage advertisements and design sure to open a wellspring of nostalgia. The museum’s collection includes a steel car from the 1930s that cost $100,000 per car (a whopping sum in those days), as well as a multitude of other cars in various states of decrepitude. The vintage cars, still and silent in their graves, still seem to echo with all of the movement and conversations that happened when they were running.

For more, check out the top 10 secrets of McCarran Park and 10 secrets of the Coney Island Cyclone, celebrating 90 years.

Subscribe to our newsletter