The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

Although the Cold War is long over, you can still see remnants of it in New York City—and in fact, you probably have without noticing it. If you’ve ever seen the faded yellow and black signs reading “FALLOUT SHELTER” on buildings around the city, it means you’ve casually strolled by a building that was once used as a place for evacuation in the event of a nuclear explosion. While it’s hard to determine the precise number of former fallout shelters around the city, several are still marked by the weathered fallout shelter signs left over from the Cold War days, when we feared annihilation at any minute.

For those who aren’t familiar with Cold War lingo, a fallout shelter is a closed space designed to shield people from fallout, or radioactive debris from a nuclear explosion formed when matter vaporizes, becomes radioactive, and falls to the ground. A fallout shelter minimizes occupants’ exposure to this dangerous material until radioactivity has decayed to safe levels and it’s alright to come out again.

Under Governor Nelson D. Rockefeller, who reigned during a time when fear of nuclear destruction was at its peak, New York had tens of thousands of fall out shelters, or even more. Rockefeller created a mandatory state shelter program in 1960, but soon made it voluntary, with building owners opting into the program. According to Gothamist, Rockefeller was apparently so supportive of fallout shelters that he built them under his Executive Mansion in Albany and his homes in Maine, Westchester County, and Fifth Avenue.

In 1961, John F. Kennedy created a national fallout shelter system, and at the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, shelters rapidly multiplied throughout New York City. This program entailed inspectors to survey buildings to determine if they could survive nuclear explosions. Identifying and certifying shelters was in the hands of local civil defense agents, and once buildings were certified, the government would hand out placards.

What did the average fallout shelter look like? The administration of fallout shelters was slightly strange, in that there may not have been federal standards for their design. It was largely up to the discretion of inspectors to determine whether a place could be a shelter. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that in 1966, New York City’s civil defense director discovered that most of the shelters had no supplies. A large reason for this was money. During the onset of the Cold War, the federal government was reluctant to fund shelters in urban areas, in favor of ones in suburban backyards.

A former fallout shelter at the London Terrace apartments in Chelsea.

“It’s all over the map in terms of how well they were designed,” said Jeff Schlegelmilch, deputy director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at the Earth Institute of Columbia University, to Gothamist. “I’ve heard stories of some where they were in the basement with sewage pipes dripping down and rats running around…The public ones are probably just large enclosed spaces where they’re able to accommodate a large number of people in a very municipal fashion.”

In general, the typical fallout shelter was a room in a building, without windows in order to stop radiation from seeping in. Naturally, it would usually be in the center of a strong, concrete building, with some shelters complete with ventilation systems, sleeping areas, and food and water supplies.

The latter, more prepared shelters were scarce and usually for high-ranking officials, while most shelters were known as “community shelters” that offered less protection. According to 6sqft, some of the only inspector guidelines for these community shelters is that they be trash-and debris-free and have a ventilation system that allowed for a “safe and tolerable environment for a specified shelter occupancy time.”

A former fallout shelter at the London Terrace apartments in Chelsea.

In 1963, The New York Times further described New York City’s fallout shelters:

“[T]he Army Corps of Engineers had identified 17,448 buildings with shelter spaces that could accommodate a total of 11,703,090 New Yorkers. The spaces were equipped with federally provided survival kits — costing roughly $2.40 per person — that featured aspirin, toilet paper, tongue depressors, appetite-suppressing hard candies and ”Civil Defense Survival Rations,” i.e., animal cracker-like biscuits.”

In reality, most fallout shelters would have done little to protect New Yorkers in the event of a nuclear attack. In fact, according to 6sqft, it’s fair to say that most New Yorkers didn’t even want to stay in fallout shelters because of the negative psychological effects associated with living in a windowless room for who knows how long.

And that’s fair, considering 1963 reports about “rats as big as dogs” in the shelter under three tenements at East 131st Street in Harlem.

An idealized fallout shelter in 1957 (in reality, they were much different.) Image via Defense Civil Preparedness/Wikimedia Commons

By contrast, a company called Shelters for Living showcased more attractive fallout shelters on the lower level of Grand Central Terminal, which were multipurpose and rec-room style. According to The New York Times, the decorator boasted that these shelters were “informal in feeling, comfortable, and as cheerful as possible, with lots of buoyant colors,” adding ”Why be drab about your shelter, when it’s more fun, and costs no more to survive in style?”

Talk about irony.

Some of the larger shelters holding thousands of people were the ones beneath the Cooper Station post office, the Lindsay Park cooperative complex in Williamsburg, under the Chase Manhattan headquarters at 28 Liberty Street, and on the 43rd floor of the Waldorf Astoria (not kidding). The Dime Savings Bank in Brooklyn gave out ”instant money for fallout shelter construction.”

As we covered, there’s also a secret former fallout shelter under the Brooklyn Bridge! In 2006, a time capsule was discovered by city workers in a vault in one of the masonry foundations of the bridge on the Manhattan side. The impressive stockpile had lain untouched for fifty years, as reported by The New York Times, filled with “water drums, medical supplies, paper blankets, drugs and calorie-packed crackers — an estimated 352,000 of them, sealed in dozens of watertight metal canisters and, it seems, still edible.” Boxes with blanket were labeled “For Use Only After Enemy Attack.”

By the 1960s, about $30 million worth of food were in New York City basements, attracting unwanted critters and vandals over the next couple of decades. In 1979, an entrepreneur named Jack Jordan got a contract to pay the city $1.06 per ton for its shelter supplies. He then sold toilet paper to a buyer in Grenada for eight cents a roll, and wanted to sell old biscuits to an animal feed manufacturer.

An in 1975, the city even had to send workers into 13,000 shelters to remove the phenobarbital (downers) from first aid kits because people would break in and steal the drugs.

Unsurprisingly, most fallout shelters have been converted back to regular usage, and the fallout shelter system has since come to an end. The agency that sponsored the program was terminated in 1979.

The former shelter at the Cooper Station post office is now used for mail purposes, while others function as storage sites and for other mundane reasons that make it hard to imagine their once crucial purposes. Then again, nothing in a crowded city like New York remains obsolete for long! These rooms could potentially still be used as fallout shelters, but there are no efforts to prepare them as such.

A former fallout shelter at Sterling Place, Crown Heights.

But what does remain are many of the black-and-yellow placards, ominously reading “FALLOUT SHELTER” with their eye-catching triangle symbol and reflective paint. According to the Civil Defense Museum, the signs expressed six points: 1. Shielding from radiation; 2. Food and water; 3. Trained leadership; 4. Medical supplies and aid; 5. Communications with the outside world; 6. Radiological monitoring to determine safe areas and time for return home.

Now that you know the former shelters are out there, you’re probably eager to get out, look for the yellow signs, and find those buildings. Here’s a map to help you out; though it already has 245 locations, keep in mind that it is not complete and may need updating.

As you can see, Manhattan is chock full of fallout shelters, with notable locations including Gramercy Park, Lenox Hill Hospital, the Chelsea School, and La Salle Academy. They’re also located throughout the Bronx, in Fordham Heights, Soundview, Mount Vernon, and Morris Park. Scroll over to Brooklyn, and you’ll find them more sparsely distributed in neighborhoods like Boerum Hill, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Park Slope, Bay Ridge, and Midwood. Staten Island seems to have missed out on them, with only three locations on the map around West Brighton (although again, the map is not complete).

Finally, Queens is also full of former shelters, most notably clustered around Elmhurst and Rego Park, Jamaica, Murray Hill, and of course, near Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

And here’s a related fun fact: there was an underground bomb shelter/luxury home that may still be hidden beneath Flushing Meadows park. Owned by Jay Swayze, a layout of the home appeared at the 1964 World’s Fair. Swayze had wanted to update the quarters of many existing bomb shelters to present the anxious public with better accommodations.

The Underground Home was supposedly demolished after the World’s Fair had closed down but many people, like Dr. Lori Walters, believe that part of the exhibit remains. Image via Narrative.ly

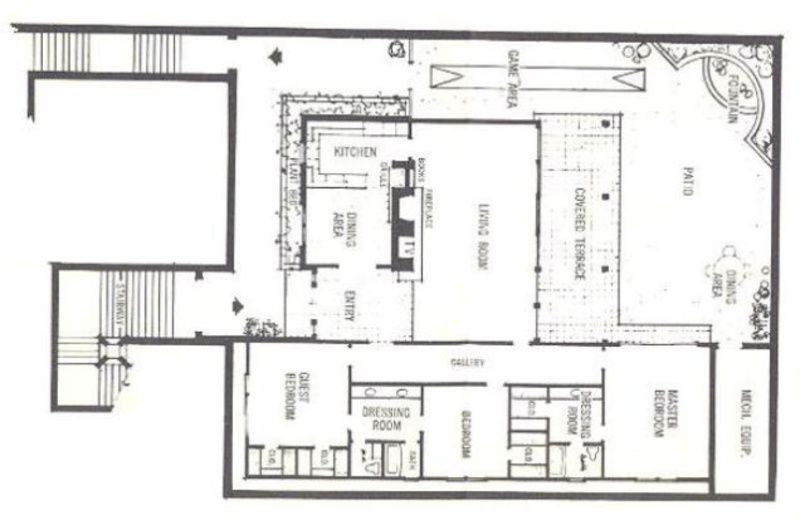

A layout of Swayze’s Underground Home at the 1964 World’s Fair, which equaled a whopping 5,600 square feet. Image via Gizmodo.

Swayze’s model of the Underground Home was built between the Hall of Science and the Port Authority Heliport. It was dubbed Block 50, Lot 5 and had 5000,000 to a million visitors according to Swayze and Fair organizers. Visitors had to descend a staircase to access the 5,600 square feet of nuke-proof luxury space, which included three bedrooms, a 20 inch thick earth quake resistant steel shell, and air-conditioning. Many historians are not convinced that the structure was completely demolished.

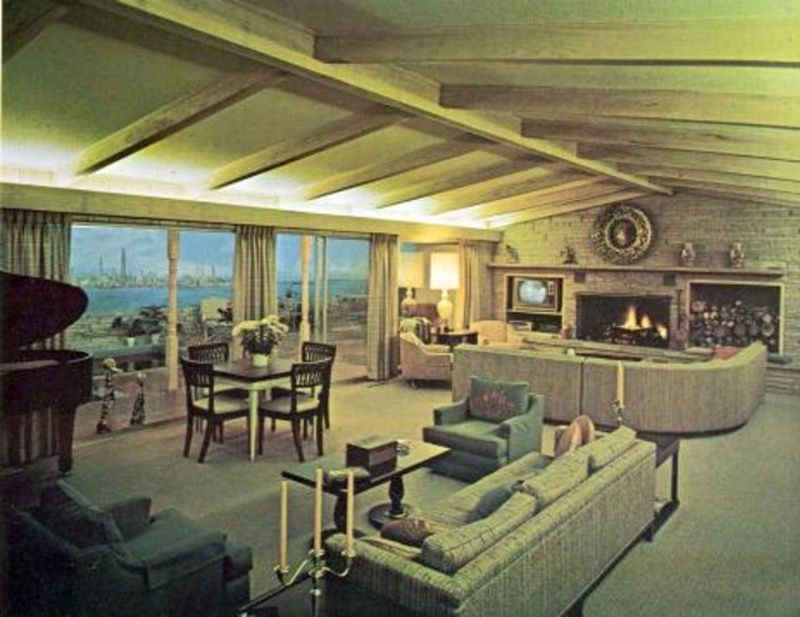

A view from inside an underground home in Colorado similar to Jay Swayze’s exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair (from the exhibit’s souvenir brochure). Image via Gothamist.

So the next time you’re out and about in New York City, keep your eyes peeled for the fallout shelter signs—because the building you walked by might’ve once had a far more interesting purpose than it does now.

Next, check out Fun Maps: Look at This Disturbingly Accurate Soviet Map of NYC in the Cold War and The Top 10 Secrets of Fort Tilden State Park in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter