How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

The Staten Island Ferry is one of New York City’s most easily recognizable transportation systems. The bright, burnt orange of the boats transporting millions of passengers annually from Manhattan’s Whitehall Terminal to St. George’s Ferry Terminal on Staten Island are the only way to get there and back (unless you have your own boat).

With origins dating back to the 1700s, a form of the Staten Island Ferry has been around for as long people lived on the borough needing a means of egress. Naturally then, this NYC ferry system has some interesting secrets to share. From fake tragedies to uses as prisons, check out our top 13 secrets of the Staten Island Ferry.

In Battery Park there stands a statue that remembers an unbelievable tragedy, that of a ferry being attacked by an octopus nearly half the size of the boat. The story goes that on a ferry that left the harbor on the early morning of November 22, 1963, 400 passengers disappeared after being pulled into the water to vanish (almost) without a trace.

The remains of the ship being found with large suction cup-shaped marks on their sides lead scientists to one conclusion: an octopus had destroyed the ship. The only reason the tragedy has been “forgotten” is that it occurred on the day of JFK’s assassination.

In truth, as you may have guessed, this event never actually occurred. But the tragedy lives on in the bronze memorial put in place by an artist Joseph Reginella. It isn’t meant to confuse or frighten but rather to cause wonder. The monument stands for creativity and love of all things weird that live in the hearts of every New Yorker.

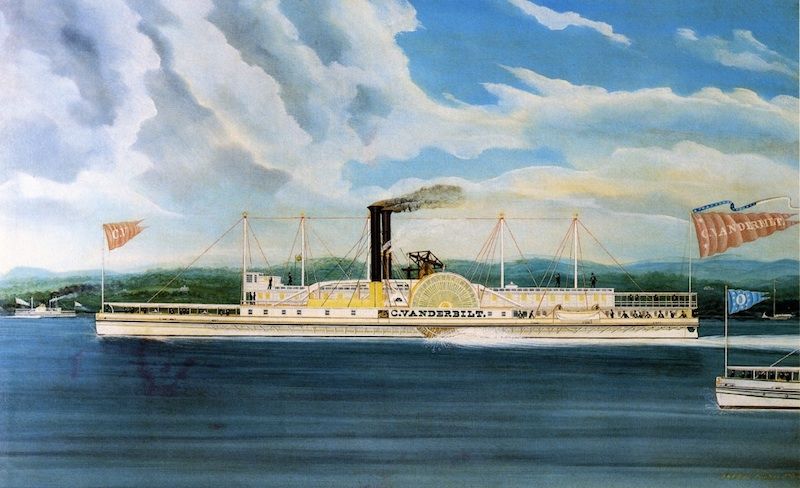

Painting by James and John Bard of the C. Vanderbilt, a Hudson River steamer owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The Vanderbilt family has a deep connection with New York City. With their hands (and money) in many endeavors across the city, it might not come as a surprise that they have something to do with the origins of the Staten Island Ferry. Despite becoming one of the richest and most families in the city, their beginnings were fairly meager.

In 1810 an industrious 16-year-old Cornelius Vanderbilt received $100 for his birthday. Instead of doing what most normal 16-year-olds would do with a hundred dollars, he bought a periauger boat and started a ferry and freight service to take people and cargoes of fish, produce from Manhattan to Staten Island. He payed his mother back the $100, adding an extra $1,000 to what was initially a bet he couldn’t complete an impossible task of starting a ferry service.

Eventually, his business grew and Cornelius’ brother-in-law took control over the first motorized ferry in New York. With the help of his brother in law Cornelius bought up the competition, built the Staten Island Ferry route, and became one of the world’s richest men all because he bought a boat at 16.

Although the ferry currently has a reputation for being one of the best free attractions in the city, this wasn’t always the case. In its long history, the boat trip has cost anywhere from a nickel to fifty cents per passenger.

On July 4, 1997, this all changed when the cost was revoked and anyone who could make it on time could take a trip across the river. However, for the city, it isn’t quite as cheap. For every single passenger aboard one of the boats, the city has to pay $5.87 which, although may not sound high, is an incredibly pricey endeavor when you consider its 22 million annual riders.

During the 9/11 terror attacks, the Staten Island Ferry along with all other ferries serving the city, relocated tens of thousands of people out of harm’s way and into safety in what the Coast Guard called the 9/11 Boatlift. Courageous ship captains docked their boats in nearly zero visibility air as the smoke and debris had completely filled the air. Nevertheless, the captains persevered and saved countless lives through their bravery.

Beyond saving the lives of individuals, the ferries also brought across emergency personnel and equipment. Although often unsung, there is no denying that the captains and crew of the city’s ferry system were heroes that day.

In 1987, the severe overcrowding of Rikers Island Prison forced Mayor Ed Koch to look for space elsewhere. Explaining in a New York Times article, Koch never again wanted “‘never again be [to be] in the situation where we once were, when we had to free prisoners because we didn’t have enough jail space.”

With a population of 14,700, Rikers was 1,000 people over capacity so Koch came up with the plan to convert two Staten Island Ferry boats into barges that would sit off the coast of the Bronx holding 162 inmates each. Many locksmiths turned down the job to redesign the engine room so inmates couldn’t get in, but Thomas King, owner of Advance Lock and Key in Midland Beach took up that task, installing high security locks on the doors and welded special boxes on each door in order to get to them.

Not meant as a temporary solution, two additional facilities were being proposed to be built in upstate New York as the city predicated the continued increase in the number of arrests and convictions, mainly drug-related.

Plenty of controversy remains over the fact that the over population in inmates should not be fixed by making more room, instead more effort should be made to create alternative-sentencing programs and reduce the numbers of detainees, as the executive director of the Correctional Association of New York, Robert Gangi explained then.

Today, the plans for a new facility have approached again with the worsening and severely dilapidated condition of the prison island, with a temporary Kew Gardens facility in the works. The Department of Corrections stopped using the Rikers ferries in 1997, said DNAinfo.

We once came across a strange scene: a Staten Island Ferry far away from its usual route, traveling up north up the Hudson River. After posing the question to our Twitter and Instagram followers, we got some fun answers.

One suggested a midlife crisis, while other responses concluded maybe it was a charter or maintenance run, or even a movie shoot. Eventually we got a comment from Louis Pons, who works for the ferry and says they go north to train new captains.

So if you ever see one of these bright orange ferries moving up the Hudson. You’re not seeing things, you’re just witnessing a captain in training!

The separation of sexes in the photo above may seem as though men and women were being segregated. But the explanation is actually fairly guiltless. In the early years of the NYC ferry, restroom were split on either side of the boats (men on one, women on the other). To make it easier for passengers to locate their respective toilets, these signs were made so they wouldn’t circle the boats aimlessly trying to find them.

During the Civil War, the US Navy wanted to create a blockade surrounding the ports of the south in order to force their economy to buckle. The problem with this plan was that the ships the Navy deployed were just too big. In order to solve this problem, they turned to New York City and its ferries, purchasing three ships, the Southfield I, Westfield I, and the Clifton I, for almost double their worth at a staggering $180,000.

The ships were then modified with guns and armories and sent to Texas and New Orleans where they made an invaluable addition to the team before their eventual destruction at Confederate hands.

Today, anyone who has seen the Staten Island Ferry will know that it has an incredibly distinctive look. It’s orange, a very, very, bright orange. The ferries originally used to be white, like many of the other NY Waterway ferries today. But in 1926, the white was dropped in favor of a reddish-marroon, and then again to the municipal orange still used today. The color was changed so the boats could be seen heavy fog and snow. While the color may not be the most attractive, safety and its uniqueness makes us like the distinctive orange hue of our boats.

Carrying over 22 million passengers per year the ferry ride between Manhattan and Staten Island is the single busiest route in the entirety of the United States and it isn’t hard to see why. When you combine commuters and tourists, it isn’t hard to imagine why people would want to use it. That and the fact that it is the only way to get from Staten Island to Manhattan, and vice versa, without a car.

Before the Staten Island Ferry was a person only vehicle it used to move other modes of transportation- and we don’t mean just cars. In the 19th century, the ferry moved horses. Eventually, horses were (unfortunately) replaced by cars and they too were allowed on the boat for a meager fee of $3 (even after the elimination of the ticket cost for people). After the September 11 attacks, however, the ferry banned cars and they haven’t been seen since. Except in that one scene from the most recent Spider-Man movie (read on to our next secret to see what exactly we’re talking about).

The Staten Island Ferry is the backdrop of countless television shows and films including Working Girl (1987), The Dark Knight (2008), and Sex and the City. The scenic view of Manhattan, the Statue of Liberty, and countless other New York monuments makes it the perfect filming location.

One of the most recent, and most exciting, additions to the ferry’s long list of film roles is in the 2017 Spider-Man: Homecoming. In this film, our friendly neighborhood Spider-Man saves the ferry from certain destruction by holding it together with his homemade synthetic webbing and his superhuman strength. Hopefully, for the people of New York, we’ll never actually need the help of Spider-Man.

Later, in 1901, a ferry was leaving the Whitehall port when a Jersey Central Ferry rammed into its side causing the boat to sink almost instantly. Fortunately out of the 995 passengers aboard the ship only five lost their lives. This major incident was what ended private operations of the city’s ferry systems, moving into the control of the City’s hands.

Even as the City took control, accidents still happened. A bombing, deadly machete attack, and numerous other collisions would occur over the course of the 1900s.

In what we’re sure will come as a relief to most New Yorkers, the ferry has been incredibly safe over the last couple of years with the last major event occurring in 2003 where the collision with a maintenance pier caused the death of 11 people. While this is still a recent and painful memory there is absolutely no need to worry as the Staten Island Ferry takes every precaution to be as safe as physically possible.

Next, check out 4 Times NYC Was Rescued by Ferries and go see the Transit Museum’s exhibition that traces the impact of transportation on Downtown Brooklyn.

Subscribe to our newsletter