After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

A visionary model of cooperation or a planning and architectural nightmare? Co-op City has been viewed both ways, but for many New Yorkers it remains an enigma, tucked away in the urban periphery of the northeast Bronx.

To outsiders it is a collection of high rise buildings, viewed afar from the window of a passing car or train. Although highly visible, it is isolated. Inaccessible by subway, the kidney-shaped area is bounded by the New England Thruway on the west, the Hutchinson River on the east and an Amtrak line on the southeast. Its southern section is intersected by the Hutchinson River Parkway.

Co-op City offers as pure a manifestation of the Modernist ideas of Le Corbusier as exists in or around New York City. For this reason alone, anyone interested in urban planning and architecture should visit to see for themselves the tower-in-the-park prototype writ large.

But it’s not just an architectural relic from another era – there’s more to Co-op City than meets the eye. Here are 10 fun facts about this unique community.

Co-op City, encompassing over 320 acres, is one of New York’s cities-within-a-city. The development includes 15,372 units of housing in 35 high rises and 236 townhouses spread across several superblocks. Besides housing, the complex also includes shopping centers, houses of worship, elementary, intermediate, and high schools, a college campus, public parks, and parking garages. It is served by its own power plant, weekly newspaper, public library, zip code, and security force.

Construction started in 1965 and the buildings were completed from 1968 to 1972. The high rises include ten 24-story “Chevrons,” ten 26-story “Triple Cores,” and fifteen 33-story “Towers.” The 33-story buildings, at 338 feet tall, were briefly the tallest in the Bronx until they were eclipsed by Paul Rudolph’s 400-foot tall Tracey Towers in 1973.

According to the Census, there are about 35,000 residents in Co-op City today, and about one in five are age 65 or older, a shift from its early years when it was populated primarily by families with children and had a population of around 50,000.

Co-op City was a product of a collaboration by three very different men: Robert Moses, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, and Abraham E. Kazan, a leftist former garment worker turned non-profit housing developer.

Kazan was the leader of United Housing Foundation, an organization closely affiliated with labor unions, and he had developed housing cooperatives to provide affordable housing for workers starting in the 1920s. Despite obvious ideological differences, he worked well with Rockefeller and Moses, because they shared an emphasis on and ability to implement major projects.

At Co-op City, the units were (and still are) limited-equity co-ops, meaning the residents collectively own the buildings but cannot profit from resale of their units. Rockefeller provided state loans through the Mitchell-Lama program and Moses used his power to smooth the way for project approval.

Rockefeller once complimented Kazan’s business acumen and noted that Kazan could have been successful in the private sector. In an often quoted reply Kazan asserted “I am a cooperator, interested only in building the cooperative commonwealth.”

As for Moses, he once praised Kazan as a “successful realist” and at the Co-op City groundbreaking, in language rarely associated with his master builder persona, went so far as to say that the project represented “democracy in action, socialism without communism, self-government without bureaucracy.”

Freedomland Stage Coach. Courtesy of Thomas X. Casey

Co-op City rose proverbially out of the ashes of Freedomland USA, an ambitious but short-lived attempt to create a Disneyland style amusement park in the northeast Bronx. Opening in 1960, Freedomland was a history-themed attraction formed in the shape of the 48 contiguous United States with mini-scaled rivers and mountains. It featured exhibits such as the Chicago fire in which visitors helped firefighters extinguish the blaze, once every 20 minutes.

The fun lasted until 1964, when Freedomland went bankrupt and closed. Its failure has been variously attributed to high operating costs, inability to operate in winter months, lack of exciting rides such as roller coasters, and, finally, competition from the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens.

After Freedomland went belly-up, United Housing Foundation swooped in to buy the property and adjoining land to implement its plan for Co-op City, a housing development on a similarly grandiose scale.

Undated image. Courtesy of Thomas X. Casey

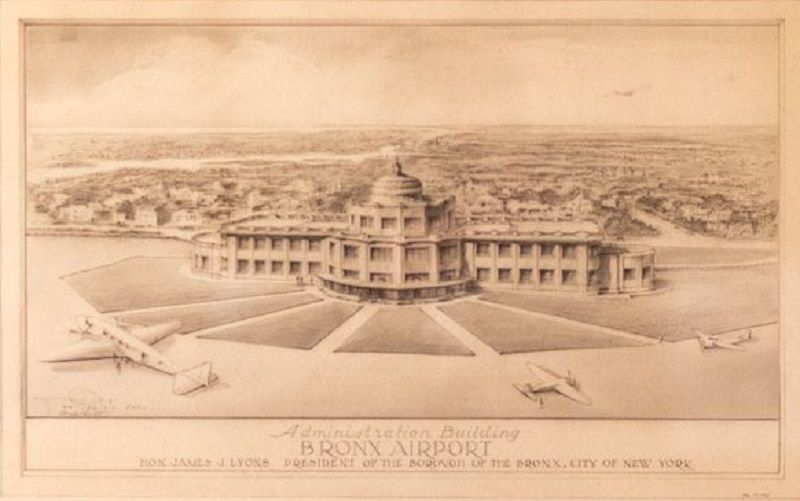

The flat marshy expanse that became Co-op City has long inspired audacious plans. Although it remained largely vacant until Freedomland was constructed, its potential for something big had long been recognized.

In 1927, both Major William F. Deegan and federal Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover called for a new airport on the site, with runways on land and seaplane access along the Hutchinson River. The Curtiss Airports Corporation purchased land there and announced plans for a Bronx Airport in June 1929. Construction was due to start in 1930, but, with the onset of the Great Depression, it floundered. Recurring efforts by Bronx political and business leaders throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s to revive it failed. Instead, Glenn H. Curtiss Airport in Queens, which opened in 1929 before the stock market crash, evolved into LaGuardia Airport.

Refusing to give up the ghost, the Bronx Chamber of Commerce opposed a 1948 proposal for a new horse racing track on the site because it was still pining for a new airport. But, with Idlewild Airport (later renamed JFK) opening that year, the Bronx Airport was superfluous. As for the race track, although blueprints were drawn up for a 25,000-seat venue, by the mid ’50s that proposal was scratched for a variety of reasons, leaving the site available for Freedomland a few years later.

Although many New York buildings and development projects have been the object of scorn from critics, the press, and the public, few have been as widely and vociferously vilified as Co-op City.

Time magazine, in a 1969 article, memorably declared that Co-op City “is relentlessly ugly: its buildings are overbearing bullies of concrete and brick.” A year later, Ulrich Franzen, a Brutalist architect one might expect to come to the project’s defense, lambasted “Co-op City’s coarsely scaled and lifeless community.”

More bluntly, former NYC Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff reveals in his new book that the first time he saw Co-op City at age 10 from the backseat of his parents’ car he thought the development “looked monstrous.”

Phil Stanziola – New York World- Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress

Much of the criticism directed at Co-op City was inspired by Jane Jacobs and her affirmation of traditional neighborhoods with low-rise rowhouses and vibrant street life. But Co-op City’s architect, Herman Jessor, was having none of it and stoutly defended tower-in-the-park development and urban renewal from a left-wing perspective.

Jessor, who earlier in his career helped to design a cooperative apartment complex featuring a hammer and sickle motif, wrote that “the “social fabric” so dear to the hearts of Jane Jacobs and her ilk does not exist. The people living in the miserable slums are not there by choice.” He added that the “people have no ‘grass roots’ in these foul rookeries… …the only solution is large scale urban renewal, the bulldozer approach.”

He argued that the city should demolish buildings in areas of the Bronx being vacated by residents moving to Co-op City and build more large scale housing projects. Lamenting that this did not happen, Jessor got in another jab at his nemesis, “Jane Jacobs will be happy – the ‘grass roots’ will not have been destroyed.”

With its 15,372 apartments, Co-op City is the largest apartment complex in New York.

By comparison, the number of units in other notable but smaller complexes include 12,271 at Parkchester, also in The Bronx; 11,250 at Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village; 5,860 at Rochdale Village in Queens, which was developed by the same team as Co-op City; 4,605 at LeFrak City; and 3,142 at the Queensbridge Houses, the city’s largest public housing development.

Co-op City is also believed to be the largest apartment complex in the US, though no authoritative source seems to keep records on the subject. Outside the US, however, Co-op is small potatoes compared to developments like Marzahn, a 59,646-unit complex built by the East German government in Berlin.

Co-op City View From Pelham Bay Park

While press coverage of Co-op City initially focused on its aesthetics, the development’s greatest existential problem turned out to be financial. During the mid 1970s, it teetered on the brink of foreclosure by the state. Cost overruns, due in part to shoddy construction, resulted in substantial increases in monthly charges to residents, known officially as “cooperators.” In response, they became uncooperative cooperators, first filing suit against the United Housing Foundation but losing in the US Supreme Court and then instituting a rent strike that lasted 13 months.

In the summer of 1976, a solution ending the strike was worked out. Essentially all sides backed off and residents gained direct responsibility for overseeing the Riverbay Corporation, the legal entity operating the co-op. (United Housing Foundation, on the other hand, ceased its development activities.)

In the years since, Co-op City has faced and overcome other financial and management problems, but the fun fact is that 45 years after its completion it is still providing affordable housing to thousands of families with a waiting list of more people who would like to move there.

When Co-op City was planned during the 1960s, it was expected that a future subway extension would link it to the rest of New York City. In fact, the Pelham Bay Park terminal of the 6 subway line is less than a mile away, though separated by highways and train tracks. The subway extension was one of many casualties of the city’s 1970s fiscal crisis and remains a dream unfilled today, with buses providing the only transit service.

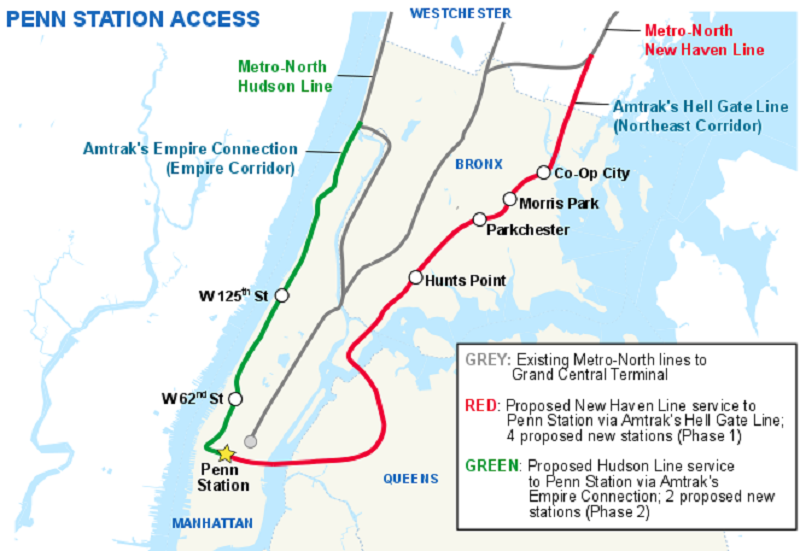

However, the current MTA capital program includes a new branch of the Metro-North New Haven Line using the Amtrak rails that run along the southeastern edge of Co-op City. Four new stations, including one at Co-op City, would provide access to New York Penn Station via the Hell Gate Bridge.

Co-op City residents will have to wait a while longer, as this will not be implemented until after the East Side Access project connecting the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal is completed, currently forecast for 2022.

In contrast to all the withering criticism that Co-op City attracted, we’ll give the final word to one of its residents, who penned a fulsome tribute called an “Ode to Co-op City.” Uncovered by Columbia University grad student Nina Wohl for her 2016 master’s thesis, here is the piece in its entirety:

“Ode to Co-op City”

From every road it comes in view

Rising up like mountain ranges do

Swinging round like a Chinese wall

In masses hold all eyes in thrall.

At night from a restless pillow

I gaze out at a lighted willow

What has so long been sought

Here at last has been wrought.

Are there any flaws, perhaps?

Who else came to fill the gaps?

There may be more perfect ventures

For those who earn debentures

For this bold new concept

No other planner were so adept.

– Israel Kovler, 5C-12F (1971)

Next, read about the Sedgwick Houses, a Modernist public housing complex in the Bronx, top 10 secrets of Pelham Bay Park, and 8 other things in NYC we can thank Robert Moses for.

Subscribe to our newsletter