New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

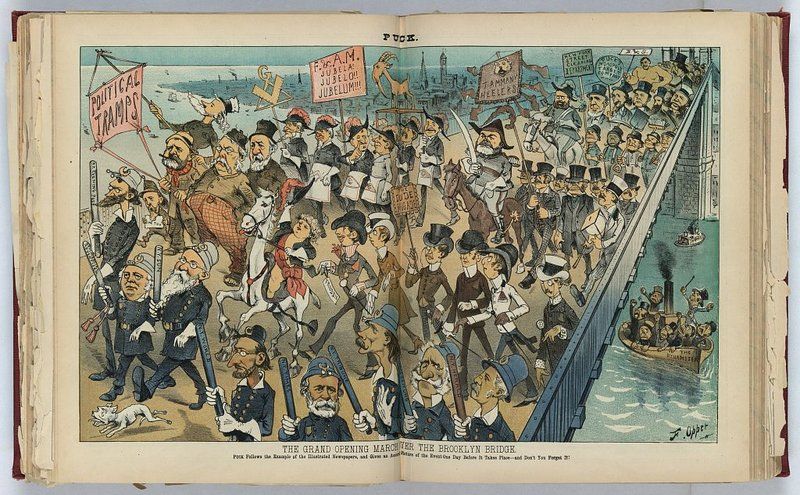

A walk over the Brooklyn Bridge is one of New York City’s most popular past times for tourists and residents alike. It’s hard not to be amazed by the granite and limestone structure which has straddled the East River for over 140 years, connecting the island of Manhattan to Brooklyn. Completed in 1883 after nearly fifteen years of construction, the bridge was an engineering marvel. At the time of its completion, the Brooklyn Bridge was the longest bridge ever built and the tallest structure in New York City’s skyline.

Over the past 140 years, this iconic landmark has been attached to countless stories and myths, secrets, and fascinating facts. From the curse of the family of engineers who designed it and the fatal stampede caused by fear of its collapse to the geological history embedded in its stone and the hidden chambers within that hosted parties, stored booze, and served as a fallout shelter, uncover the secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge here in our ever-evolving list and by joining us on our Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge walking tour!

On both the Manhattan and Brooklyn sides of the bridge, there are massive stone anchorages that were designed to secure the bridge’s cables and resist their tremendous pull. Inside the foundations on the Brooklyn side, bridge designer John A. Roebling designed eight interior spaces with 50-foot-high cathedral ceilings in anticipation of turning them into retail space. However, this plan fell through, and they have been largely used for storage and other creative purposes.

Inside the cavernous vaults, space was rented out for wine and champagne storage. The alcohol was kept at stable temperatures throughout the year and the rent helped offset the cost of the bridge (along with appeasing alcohol purveyors whose warehouses were demolished for the bridge’s construction). The New York Times reported that city records show that the “‘Luyties Brothers’ paid $5,000 for wine storage in a vault on the Manhattan side. ‘A. Smith & Company’ paid $500 a year from 1901 until 1909 for a vault on the Brooklyn side.”

The massive spaces on the Brooklyn side also played host to a series of creative art installations, performances, and events produced by Creative Time, originally in honor of the Bridge’s Centennial. A new installation was unveiled every summer from 1983 until 2001. Multiple artists over the years were commissioned to create new works addressing the “vivid historical and visual qualities of the Anchorage,” including the barrel-vaulted ceilings and massive masonry piers housing the bridge’s cables. The often immersive installations included everything from fashion shows, to sound and light installations and performances.

Today, the vaults are still used for storage but are closed to the public. They have been off-limits since 2001 when safety concerns were raised post 9/11. Their inaccessible nature makes them an even more desirable place to gain access to. In 1999, Maria Smith, a spokesperson for the D.O.T., told the Times that ”People call up sometimes and say they’d like to live there.” In fact, according to Edible Geography, a homeless person was found living in one of the vaults, discovered during a promotional visit for the film The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3. Recent visitors in the last few years have reported to us that they’ve found soil samples in jars, Department of Transportation filing cabinets filed with bridge specs, catering items lying around, and more.

Though there is not much information about it online, there is a plaque inside the anchorage on the Brooklyn side that marks the spot of a buried time capsule. The capsule was put in place for the centennial celebrations in 1983. Its contents are not to be revealed until May 24th, 2083, the bicentennial of the bridge’s completion.

The 100th anniversary of the bridge’s construction was also commemorated with special edition items like official U.S Postal stamps and a bronze medal that had a piece of the original steel cable from the span embedded in it. Tiffany & Co. even made special edition pieces for the occasion which included a sterling silver money clip with a cross-section of the bridge sculpted in relief, a sugar spoon which was a recreation of one Tiffany’s made in 1891 as part of a series honoring architectural monuments in New York, and an enamel box with a colorful panoramic view of the East River. The centennial celebrations were massive! A parade of thousands crossed the bridge and there was a spectacular lights and fireworks show.

In 2006, a veritable time capsule was discovered by city workers in a vault in one of the masonry foundations on the Manhattan side of the bridge. As reported by The New York Times, the impressive stockpile had lain untouched for fifty years. Inside the vaults workers found “water drums, medical supplies, paper blankets, drugs, and calorie-packed crackers — an estimated 352,000 of them, sealed in dozens of watertight metal canisters and, it seems, still edible.” Boxes with blankets were labeled “For Use Only After Enemy Attack.”

Many boxes were stamped with two key dates, continued The Times, “1957, when the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite, and 1962, when the Cuban missile crisis seemed to bring the world to the precipice of nuclear destruction.” There were also “several dozen boxes” containing sealed bottles of Dextran, an antithrombotic medication.

Brooklyn Bridge Beach is a highly visible waterfront, but it is rarely open to the public. On the Manhattan side of the bridge, the beach opened for just a few hours in honor of City of Water Day in 2018 and again in 2019. The event was meant to raise awareness of the city’s waterways and recreational water activities. There have been efforts made by civic groups, such as the Waterfront Alliance and the New York City Economic Development Corporation, to grant the public year-round access to the beach under the bridge, but so far that does not seem like it will happen anytime soon. The city has cited concerns over safety and water cleanliness as the main reasons for the beach remaining off-limits. Proponents of its opening say it would be a great spot to launch kayaks and enjoy the waterways of New York City.

The two towers of the Brooklyn Bridge are made of predominantly limestone from the Hudson Valley and Maine granite, and the anchorages of natural cement and granite. The natural cement came from near Rosendale, New York where there was a very successful quarry founded in 1825. This same cement was used to build the interior of the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty and fill Fort Wood which she was placed on top of. When this space was filled, it was the largest concentration of cement in the world.

The limestone blocks came from Kingston, New York, and since limestone is a sedimentary rock, there are fossils in it. Many examples of various fossil types can be found along the walls of both anchorages (though due to construction, both are inaccessible at the moment). Mandy Edgecombe, a trained naturalist and guide on our Secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge tours, tells us, “If you walk west along the blocks (after checking out the Roebling statues in the park) you will start seeing small features exposed such as rugosa corals, brachiopods, and we even found a trilobite!” The area these blocks were mined from was covered by a warm, shallow sea about 400 million years ago and is called the Rondout Formation by geologists.

Though looking at the high pointed arches on the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge today might conjure up images of Gothic cathedrals rather than pyramids and mummies, the towers were originally designed to look Egyptian. Soaring above any other structure in the New York City skyline at the time they were built at 276 feet high, the towers were designed by John Roebling to mimic an Egyptian-style tomb.

In 1857 plans created by Roebling, the towers were more column-like and did not have large pointed arches but instead sculptural Egyptian imagery and a more blocky aesthetic. These plans were scrapped after John’s death when his son Washington took over the design and swayed it towards the Gothic style. Washington was constantly trying to distinguish himself from his father, who was usually given all of the credit for the bridge’s design. The towers are made of a combination of New York Limestone from Rosendale, New York, and granite from Maine and Connecticut. It took six years and over 85,000 cubic yards of masonry to complete them.

John Roebling designed the Brooklyn Bridge but never got to see it to fruition. While taking compass readings in preparation for the bridge, his foot got stuck and crushed between a ferry and the dock. Doctors amputated his toes but Roebling slipped into a coma and died ultimately of tetanus. His son, Washington Roebling, took over responsibilities but suffered two attacks of caisson disease (aka the bends) as a result of ascending too quickly in the compressed air chambers used to lay the foundations underwater. Suffering from paralysis, deafness, and partial blindness, Washington Roebling turned the responsibilities over to his wife, Emily Warren Roebling. The misfortunes led some to speculate that the Roebling family was cursed.

Luckily, Emily was able to escape the supposed curse and she was the first person to cross the entire span of the bridge when it was completed in 1883. The construction of the Brooklyn Bridge was an overall debilitating affair for more than the Roebling family — at least twenty people died during the construction of the bridge and more than 100 suffered from caisson disease.

There’s some debate as to the original color of the Brooklyn Bridge. Some accounts indicate that part of the bridge was originally “Rawlins Red.” The color is based on a pigment from iron oxide near Rawlins, Wyoming, and the idea is supported by a color print by Currier & Ives from 1877 and a newspaper report from the Rawlins Times on the 100th Anniversary: “The old bridge is still sound due in part to several coats of anti-rust paint which came from Rawlins.”

But Rawlins Red may have been an undercoat, on top of which was painted what is now known as Brooklyn Bridge Tan, or two shades of buff, according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The official color of paint for the Brooklyn Bridge is less literary than either of them: “Federal Specification #20227.”

The Brooklyn Bridge is maintained and operated by the New York Department of Transportation (DOT) which runs 793 bridges and tunnels throughout New York, including the Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges, for which there are no tolls. Bridges run by other agencies, like the Throgs Neck and Whitestone which are run by the y MTA Bridges and Tunnels, do have tolls. There was a time however when it did cost one to ten cents to cross the Brooklyn Bridge.

If you wanted to cross the bridge on foot, you had to pony up one cent. It cost five cents to cross on horseback and ten cents to cross with a horse and wagon. If you were transporting cattle it would cost five cents per cow and two cents per sheep. Pedestrian tolls went away in 1891 and all other tolls were rescinded by 1911. With the passage of the congestion pricing plan in early 2019, drivers crossing the Brooklyn Bridge will be subject to the new fees (over $10), unless they head directly onto the FDR Drive north until 60th Street.

Just six days after opening to the public, a rumor quickly spread that the new bridge was about to collapse. The resulting panic caused such a massive stampede that twelve people were killed in the crush. The tragic incident started the afternoon of May 30, 1883, when a woman tripped and fell while descending the wooden stairs on the Manhattan side of the bridge. Apparently, this caused another woman to scream at the top of her lungs, which caused those nearby to rush towards the scene. The commotion sparked a chain reaction of confusion, as more and more people panicked and mobbed the narrow staircase, creating a massive pileup. Thousands were on the promenade, quickly turning the situation deadly.

The tragedy highlights the doubt in that era that a bridge could be built big enough to span the East River. With a span of 1,595 feet 6 inches, it was by far the longest bridge in the world at the time, and 50% longer than any suspension bridge ever attempted. The two stone, 276-foot-tall towers were the tallest structures in New York, except for Trinity Church’s spire.

The phrase “I have a bridge to sell you” comes from the shockingly large number of times the bridge was sold by con artists. The first instance was by a man named Peaches O’Day who made $200 from the “sale,” but George C. Parker took the scam to a whole new level. Often targeting immigrants, Parker sometimes sold the bridge up to twice per week and even made $50,000 in a single sale.

He set up counterfeit offices and offered fake documents for the sales. The police were called in regularly to remove toll booths set up by the new supposed “owners” of the Brooklyn Bridge. Parker didn’t just limit himself to the Brooklyn Bridge: he was known for selling the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Statue of Liberty, and Grant’s Tomb as well. Parker ended up incarcerated at Sing Sing, where he died.

Inside the foundations on the Brooklyn side, bridge designer John A. Roebling had envisioned a shopping arcade, called the Brooklyn Bridge Anchorage. According to Julie Golia, a historian of the Brooklyn Historical Society, Roebling “gave the inside [of each] the same Gothic design as the towers, with beautiful 50-foot-high cathedral ceilings. But that plan fell through, and for most of history, they’ve been municipal storage.”

The functional use of the anchorages is to secure the cables that span and essentially hold up the bridge. The cable strands are bolted into rod-iron eye-bar chains encased inside the masonry of the anchorage and then an anchor plate holds the end of each chain in place.

A year after the opening, P.T. Barnum helped to reassure the public of the bridge’s safety (while publicizing his circus) by leading a parade of 21 elephants over the bridge. The stunt is memorialized in the children’s book, 21 Elephants and Still Standing. The elephants made it safely across the bridge and the structure withstood their weight, which wasn’t surprising. The bridge was overbuilt to be six times stronger than necessary, with a capacity of 18,700 tons, or over 2,500 African elephants.

In 2017, Staten Island sculptor Joe Reginella took the story of the elephant crossing and twisted it into a fictional tale that inspired the fake memorial you see in the picture above. Reginella crafted the sculpture to commemorate the lives lost in the Brooklyn Bridge Elephant Stampede of October 24, 1929, the same day the stock market crashed. Of course, this never really happened. Reginella has also crafted memorials to an octopus attack on a ferry in a Staten Island harbor and a UFO tugboat abduction.

Continuing a trend started in Europe on bridges in Paris and Rome, lovers crossing the Brooklyn Bridge left mementos of their romance by affixing locks to the bridge’s structure. The problem with this romantic gesture is that the weight of the love locks can damage the bridge and their removal costs the NYC Department of Transportation $100,000. In 2013, over 34,000 love locks were removed. The locks caused a wire to snap back in 2016, leading to extensive delays and repairs.

To help curb the placement of love locks on the bridge, the DOT got creative with signage and paid homage to a Brooklyn staple, lox. The borough’s love of lox was incorporated it into a “punny” sign that read, “NO LOCKS, YES LOX.” Though as evidenced by this photo, it doesn’t seem to be very effective. Fun fact: In 2018, Acme Smoked Fish and Zucker’s Bagels set the world record for the largest salmon lox bagel at an event in Brooklyn.

Building the Brooklyn Bridge was an amazing engineering feat and the success of its design is evident in the fact that it is still standing strong today. Many lives were lost in the construction of the bridge and one of the riskiest parts of the process was installing the caissons, the base on which the towers rest, at the bottom of the river.

When digging into the riverbed, on the Manhattan side, fossils were found which indicated that the riverbed had not shifted in several million years. Washington Roebling, who had already seen too many of his workers suffer from caisson disease (the bends), decided that this was enough evidence to safely halt digging thirty feet above the bedrock. What means essentially is that the Manhattan side tower sits not atop bedrock like the Brooklyn side, but on sand. It would have taken another year more possible casualties if the digging continued into the bedrock.

Next, check out Vintage Construction Photos of NYC’s Bridges and The 14 Best Things to Do in DUMBO

Subscribe to our newsletter